|

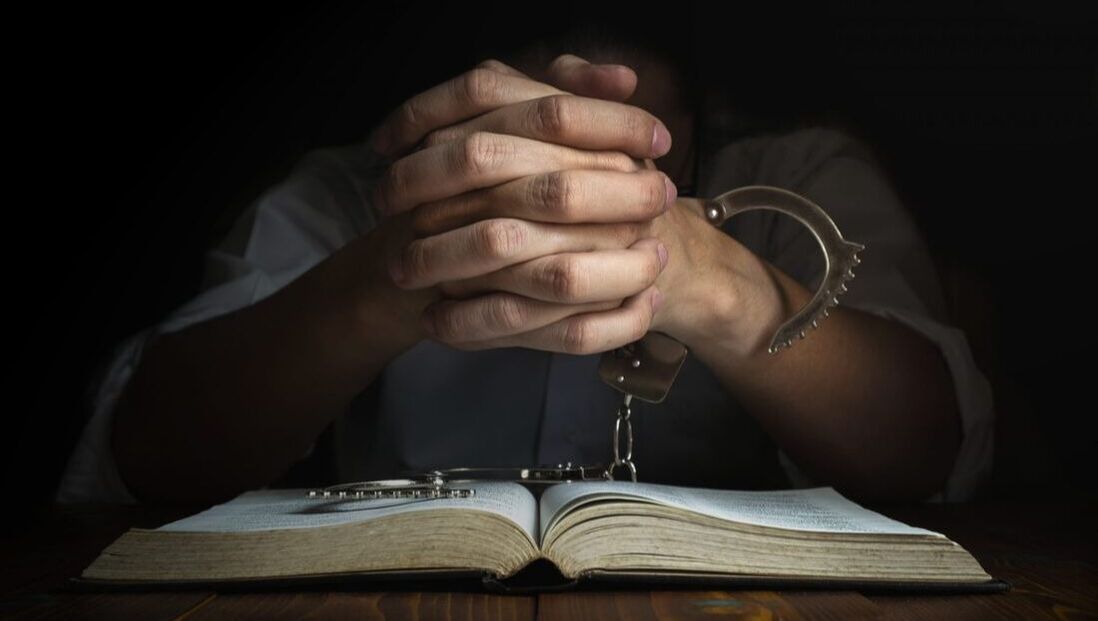

Today Protect The 1st filed an amicus brief, drafted by the organization’s regular outside counsel and joined by several other groups, asking the Supreme Court to hear Thompson v. Marietta Education Association. The case asks whether public employees have a First Amendment right to decline to be represented by unions. Under Ohio law, Jade Thompson, a public-school teacher, is required to accept the Marietta Education Association as her exclusive representative in bargaining arrangements. Thompson, however, isn’t a member of the Association, and would—but for the law—reject the union’s representation.

There is something fundamentally wrong—and unconstitutional—about a law that requires you to accept the message or representation of another group. Recognizing that the First Amendment rights to speak and associate freely with others also includes the rights to not speak and to decline such association, Protect the 1st and a large group of other public policy research organizations and advocacy groups joined a chorus of other amici today urging the Court to hear the case. The brief can be read here. The guarantee of freedom of worship contained in the First Amendment poses a grim if serious question: Do condemned prisoners have the right to have a clergy member present at their execution?

A federal law passed in 2000 – the Religious Land Use and Institutionalized Persons Act – sweeps aside zoning and other restrictions on the exercise of religious institutions within prisons, allowing inmates access to clergy and religious facilities. The State of Alabama was poised to execute an inmate, Willie B. Smith, for a 1991 murder, without the presence of his minister. On early Friday, Amy Coney Barrett joined three liberal justices to compel Alabama to permit Smith’s minister to be present at his execution. Justice Kagan wrote, “Alabama has not carried its burden of showing that the exclusion of all clergy members from the execution chamber is necessary to ensure prison security. So the State cannot now execute Smith without his pastor present, to ease what Smith calls the ‘transition between the worlds of the living and the dead.’” Our criminal justice system incarcerates almost 2.3 million people. The allowance of a minister for Smith is a relatively minor burden for the prison, but it serves as an important principle that broadly extends other applications of an important First Amendment right – the freedom of worship. In important ways, the Court is upholding the ability, as scripture says, to “continue to remember those in prison as if you were together with them in prison.” On Friday, the U.S. Supreme Court took a stand, 6-3, for the freedom to worship over an onerous coronavirus-related order. The Court ordered the State of California to end its blanket ban on all indoor religious services as discriminatory. California was the only state to ban all indoor religious services. But the court did allow the state to limit indoor worship services to 25 percent of capacity, and left in place a ban on singing and chanting.

Justice Neil Gorsuch, though in the majority, issued an opinion declaring that he would have preferred a stronger ruling to protect the freedom to worship under the First Amendment. Some excerpts: Since the arrival of COVID–19, California has openly imposed more stringent regulations on religious institutions than on many businesses. The State’s spreadsheet summarizing its pandemic rules even assigns places of worship their own row … When a State so obviously targets religion for differential treatment, our job becomes that much clearer … The State presumes that worship inherently involves a large number of people. Never mind that scores might pack into train stations or wait in long checkout lines in the businesses the State allows to remain open. Never mind, too, that some worshippers may seek only to pray in solitude, go to confession, or study in small groups … California has sensibly expressed concern that singing may be a particularly potent way to transmit the disease, and it has banned singing not just at indoor worship services, but at indoor private gatherings, schools, and restaurants too… Even if a full congregation singing hymns is too risky, California does not explain why even a single masked cantor cannot lead worship behind a mask and a plexiglass shield. Or why even a lone muezzin may not sing the call to prayer from a remote location inside a mosque as worshippers file in. In her first signed opinion in a religious-liberty case, Justice Amy Coney Barrett chimed in: “Of course, if a chorister can sing in a Hollywood studio but not in her church, California’s regulations cannot be viewed as neutral.” Underlying these opinions is a sense that Sacramento has a fine appreciation for the First Amendment rights of business – especially the movie business – but not for the thousands of churches, synagogues, mosques and temples in California communities. In Norse mythology, trolls hide in wait for their victims. On the online world today, they destroy lives and reputations without ever being seen.

Kashmir Hill of The New York Times wrote a piece about a software engineer in the UK who is being victimized by an internet troll – including false accusations about him being a pedophile, as well as being “a former janitor” masquerading as an IT consultant. Not content to destroy this man’s reputation and livelihood, the troll went on to do the same to the software engineer’s wife, brother-in-law, cousin and teenage nephew. As she was writing the piece, Ms. Hill interviewed the person linked by metadata to these attacks. Soon, Ms. Hill herself and her husband were getting hit with lurid accusations on such select sites as Cheaterbot and BadGirlReports. One of the sites that carried the reputational attacks on the software engineer was Ripoff Report. Hill writes: Ripoff Report, like the others, notes on its site that, thanks to Section 230 of the federal Communications Decency Act, it isn’t responsible for what its users post. “If someone posts false information about you on the Ripoff Report, the CDA prohibits you from holding us liable for the statements which others have written. You can always sue the author if you want, but you can’t sue Ripoff Report just because we provide a forum for speech.” With that impunity, Ripoff Report and its ilk are willing to host pure, uncensored vengeance. Google has taken a stronger hand in deleting reputational attacks of a sexual nature. It has also downgraded Ripoff Reports. But the question of what to do about trolls remains. Section 230 defends third-party posts, so it defends these kinds of ugly attacks. At the same time, without Section 230 the robust world of online speech we know today would be a ghostly realm of anodyne, curated and legal-reviewed speech. Protect the 1st is in discussions with leading Members of Congress in a quest to see if it is possible to close loopholes that allow such obvious personal defamation without degrading freedom of speech. Can that needle be threaded? |

Archives

June 2024

Categories

All

|

ABOUT |

ISSUES |

TAKE ACTION |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed