|

California, known for its progressive values and innovation, is increasingly becoming a battleground over the regulation of speech. The state's regulatory, political, and educational bodies are systematically encroaching on the fundamental right to free expression, attempting to manage and control speech in ways that undermine the First Amendment in the schools and among businesses.

When California sets a precedent, the implications for free speech rights across the country are profound, warranting close scrutiny and robust debate. Yet in California, recent actions reflect a shift towards control and censorship, challenging this essential liberty. Consider the legal battle involving X Corp., formerly known as Twitter. The company has been fighting against surveillance and gag orders that infringe on X’s First Amendment rights while also threatening the Fourth and Sixth Amendment rights of its users. When the government demands access to personal data stored by companies like X Corp. and then issues Non-Disclosure Orders (NDOs) to keep this secret, it coerces companies into acting as government spies, unable to speak to their users about the breaches of their privacy. This case highlights a broader pattern in California's legislative and judicial landscape. One recent law, California Bill AB 587, mandates that social media companies disclose their content moderation practices. Legal scholar Eugene Volokh has argued that this law pressures companies to engage in viewpoint discrimination, reveal their internal editorial processes, and do the government's bidding in managing speech. How would that be different from requiring newspapers to explain their editorial decisions to the government? These laws and regulations are often claimed to be justified as necessary for combating hate speech, misinformation, and harassment; however, they impose significant burdens on companies and threaten to stifle free expression. A court recently ruled against X Corp. in its attempt to block the law requiring it to disclose to the government the internal deliberations of its content moderation policies. While transparency in moderation practices might seem beneficial, the forced disclosure could lead to state-enforced censorship and coercion of private editorial processes, undermining the very principles of free speech the First Amendment is meant to protect. The state's approach to managing speech extends beyond digital platforms. In a recent disturbing case, an elementary school disciplined a first grader for drawing a benign picture with the phrase “Black Lives Matter.” Being young and probably unaware of the larger sensitivities, this elementary school child added: “any life.” The school promptly disciplined the child without telling her parents. This overreaction reflects a broader problem with educational institutions, driven by a hypersensitivity to the perceived (or mis-perceived) demands of political correctness, that end up punishing even innocent expressions of empathy and solidarity. A federal court's support for the school's actions further highlights the precarious state of free speech rights in educational settings, from elementary school up to graduate school, law school, and medical school. California's aggressive stance on speech regulation also manifests in its legal battles over the Second Amendment. A controversial state law tried to impose attorney's fees on plaintiffs challenging gun restrictions even if they win their case, but lose any small portion of their claims. This tactic aims to deter legal challenges and silence dissent, directly contravening First Amendment rights. The law’s similarity to a Texas statute targeting abortion challengers underscores a worrying trend of using financial penalties to stifle constitutional challenges. These cases collectively illustrate a dangerous trajectory in California's approach to managing speech. The state's efforts to regulate and control various forms of expression, whether online, in schools, or through legal deterrents, represent a direct assault on the First Amendment. The complexities and nuances of speech, inherently messy as they are, cannot and should not be sanitized by governmental oversight. Fortunately, the U.S. Supreme Court remains a bulwark against regulations violating the First Amendment. The Court’s decision in AFP v. Bonta, which struck down California's requirement for non-profit organizations to disclose their donors, was a significant victory for free speech. The Court recognized that such disclosure requirements pose a substantial burden on First Amendment rights, particularly by exposing donors to potential harassment and retaliation. This case reinforces the principle that anonymity in association is crucial for protecting free expression and dissent. In the recent NetChoice opinion, a majority of the Court gave a ringing endorsement of editorial freedom, even while sending the case back for a more detailed review of the laws. We remain optimistic the Supreme Court will likewise rein in California’s antagonism toward the First Amendment if, and when, it has the opportunity. The recent session of the U.S. Supreme Court will likely be remembered for two major rulings implicating fundamental separation of powers doctrine: Trump v. United States, establishing presumptive immunity from prosecution for official presidential acts; and Loper Bright Enterprises v. Raimondo, dispensing with the long-established “Chevron Two Step” granting deference to a federal agency’s interpretation of statutes. In both instances, the Court reaffirmed our constitutional system of checks and balances, including protection against encroachment on the powers and privileges of one branch of government by another.

Against the backdrop of those headline-dominating developments, the Supreme Court also took on several important First Amendment cases, with results that were constitutionally sound. Below are the highlights – and summaries – of the Court’s First Amendment jurisprudence released in recent weeks. Food and Drug Administration v. Alliance for Hippocratic Medicine In a unanimous ruling, the Supreme Court rejected a challenge to the Food and Drug Administration’s regulation of the abortion drug mifepristone. Little noticed by the media, the Court’s opinion also firmly nailed down the conscience right of physicians to abstain from participating in abortions and prescribing the drug. Writing for the Court, Justice Kavanaugh said that the Church Amendments, which prohibit the government from imposing requirements that violate the conscience rights of physicians and institutions, “allow doctors and other healthcare personnel to ‘refuse to perform or assist’ an abortion without punishment or discrimination from their employers.” From now on, any effort to restrict or violate the conscience rights of healers will go against the unanimous opinion of all nine justices of the U.S. Supreme Court. Vidal v. Elster The Supreme Court, in another unanimous decision, overturned a lower court ruling that found that the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office’s denial of an application to trademark a phrase including the name “Trump” violated the filer’s First Amendment rights. Writing for the Court, Justice Thomas wrote that “[o]ur courts have long recognized that trademarks containing names may be restricted.” But such trademark restrictions, while “content-based” must be “viewpoint neutral.” This opinion prevents commercial considerations to scissor out pieces of the national debate. While the decision rejected a novel First Amendment claim to a speech-restricting trademark, it affirms sound First Amendment principles and protects the speech of all others who would discuss and debate the virtues and vices of prominent public figures. The Court was right to refuse the endorsement of a government-granted monopoly on a phrase about a presidential candidate. NRA v. Vullo NRA v. Vullo – yet another unanimous opinion – cleared the way for the National Rifle Association to pursue a First Amendment claim against a New York insurance regulator who had twisted the arms of insurance companies and banks to blacklist the group. Maria Vullo, former superintendent of the New York State Department of Financial Services, met with Lloyd’s of London executives in 2018 to bring to their attention technical infractions that plagued the affinity insurance market in New York, unrelated to NRA business. Vullo told the executives that she would be “less interested” in pursuing these infractions “so long as Lloyd’s ceased providing insurance to gun groups.” She added that she would “focus” her enforcement actions “solely” on the syndicates with ties to the NRA, “and ignore other syndicates writing similar policies.” The Court found for the NRA, writing that, “[a]s alleged, Vullo’s communications with Lloyd’s can be reasonably understood as a threat or as an inducement. Either of those can be coercive.” The Supreme Court’s opinion vacates the Second Circuit’s ruling to the contrary and remands the case to allow the lawsuit to continue. As the Court wrote, “the critical takeaway is that the First Amendment prohibits government officials from wielding their power selectively to punish or suppress speech, directly or (as alleged here) through private intermediaries.” And we wholeheartedly agree – censorship by proxy is still government censorship. Moody v. NetChoice In one of two cases involving the nexus of government and social media, the Court seemed to punt on making a final decision on the constitutionality of laws from Florida and Texas restricting the ability of social media companies to regulate access to, and content on, their platforms. Many commentators believed the Court would resolve a split between the Fifth Circuit (upholding a Texas law restricting various forms of content moderation and imposing other obligations on social media platforms) and the Eleventh Circuit (which upheld the injunction against a Florida law regulating content and other activities by social media platforms and by other large internet services and websites). The Court’s ruling was expected to resolve the hot-button issue of whether Facebook and other major social media platforms can depost and deplatform. Instead, the Court found fault with the scope and precision of both the Fifth and the Eleventh Circuit opinions, vacating both of them and telling the lower courts to drill down on the varied details of both laws and be more precise as to the First Amendment issues posed by such different provisions. The opinion did, however, offer constructive guidance with ringing calls for stronger enforcement of First Amendment principles as they relate to the core activities of content moderation. The opinion, written by Justice Elena Kagan, declared that: “On the spectrum of dangers to free expression, there are few greater than allowing the government to change the speech of private actors in order to achieve its own conception of speech nirvana.” Murthy v. Missouri In what looked to be a major case regarding the limits of government “jawboning” to get private actors to restrict speech, the Court instead decided that Missouri, Louisiana, and five individuals whose views were targeted by the government for expressing misinformation could not demonstrate a sufficient connection between the government’s action and their ultimate deplatforming by private actors. Accordingly, the Court’s reasoning in this 6-3 decision is that the two states and five individuals lacked Article III standing to bring this suit. A case that could have defined the limits of government involvement in speech for the central media of our time was thus deflected on procedural grounds. Justice Samuel Alito, in a fiery dissent signed by Justices Clarence Thomas and Neil Gorsuch, criticized the punt, calling Murthy v. Missouri “one of the most important free speech cases to reach this Court in years.” Fortunately, NRA v. Vullo, discussed above, sets a solid baseline against government efforts to pressure private actors to do the government’s dirty work in suppressing speech the government does not like. Later cases will, we hope, expand upon that base. Secret communications from the government to the platforms to take down one post or another is inherently suspect under the Constitution and likely to lead us to a very un-American place. Let us hope that the Court selects a case in which it accepts the standing of the plaintiffs in order to give the government, and our society, a rule to live by. Gonzalez v. Trevino Protect The 1st has reported on the case of Sylvia Gonzalez, a former Castle Hills, Texas, council member who was arrested for allegedly tampering with government records back in 2019. In fact, she merely misplaced them, and was subsequently arrested, handcuffed, and detained in what was likely a retaliatory arrest for criticizing the city manager. In turn, Gonzalez brought suit. Gonzalez’s complaint noted that she was the only person charged in the past 10 years under the state’s government records law for temporarily misplacing government documents. In 2019’s Nieves v. Bartlett, the Supreme Court found that a plaintiff can generally bring a federal civil rights claim alleging retaliation if they can show that police did not have probable cause. The Court also allowed suit by plaintiffs claiming retaliatory arrests if they could show that others who engaged in the same supposedly illegal conduct, but who did not engage in protected but disfavored speech, were not arrested. The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit threw out Gonzalez’s case, finding that she would have had to offer examples of those who had mishandled a government petition in the same way that she had but – unlike her – were not arrested. The Supreme Court, by contrast, found that, “[a]lthough the Nieves exception is slim, the demand for virtually identical and identifiable comparators goes too far.” The Court thus made it a bit easier for the victims of First Amendment retaliation to sue government officials who would punish people for disfavored speech. The controversy will now go back to the Fifth Circuit for reconsideration. *** While the Court avoided some potentially landmark decisions on procedural grounds, and offered a mixed bag of decisions concerning plaintiffs’ ability to obtain redress against potential First Amendment violations, the majority consistently showed a strong desire to protect First Amendment principles – shielding people and private organizations from government-compelled speech. NetChoice v. Texas, FloridaWhen the U.S. Supreme Court put challenges to Florida and Texas laws regulating social media content moderation on the docket, it seemed assured that this would be one of the yeastiest cases in recent memory. The Supreme Court’s majority opinion came out Monday morning. At first glance, the yeast did not rise after all. These cases were remanded back to the appellate courts for a more thorough review.

But a closer look at the opinion shows the Court offering close guidance to the appellate court, with serious rebukes of the Texas law. Anticipation was high for a more robust decision. The Court was to resolve a split between the Fifth Circuit, which upheld the Texas law prohibiting viewpoint discrimination by large social media platforms, while the Eleventh Circuit upheld the injunction against a Florida law regulating the deplatforming of political candidates. The Court’s ruling was expected to resolve once and for all the hot-button issue of whether Facebook and other major social media platforms can depost and deplatform. Instead, the Court found fault with the scope and precision of both the Fifth and the Eleventh Circuit opinions, vacating both of them. The majority opinion, authored by Justice Elena Kagan, found that the lower courts failed to consider the extent to which their ruling would affect social media services other than Facebook’s News feed, including entirely different digital animals, such as direct messages. The Supreme Court criticized the lower courts for not asking how each permutation of social media would be impacted by the Texas and Florida laws. Overall, the Supreme Court is telling the Fifth and Eleventh to drill down and spell out a more precise doctrine that will be a durable guide for First Amendment jurisprudence in social media content moderation. But today’s opinion also contained ringing calls for stronger enforcement of First Amendment principles. The Court explicitly rebuked the Fifth Circuit for approval of the Texas law, “whose decision rested on a serious misunderstanding of the First Amendment precedent and principle.” It pointed to a precedent, Miami Herald Publishing Co. v. Tornillo, in which the Court held that a newspaper could not be forced to run a political candidate’s reply to critical coverage. The opinion is rife with verbal minefields that will likely doom the efforts of Texas and Florida to enforce their content moderation laws. For example: “But this Court has many times held, in many contexts, that it is no job for government to decide what counts as the right balance of private expression – to ‘un-bias’ what it thinks is biased, rather than to leave such judgments to speakers and their audiences.” The Court delved into the reality of content moderation, noting that the “prioritization of content” selected by algorithms from among billions of posts and videos in a customized news feed necessarily involves judgment. An approach without standards would turn any social media site into a spewing firehose of disorganized mush. The Court issued a brutal account of the Texas law, which prohibits blocking posts “based on viewpoint.” The Court wrote: “But if the Texas law is enforced, the platforms could not – as they in fact do now – disfavor posts because they:

So what appeared on the surface to be a punt is really the Court’s call for a more fleshed out doctrine that respects the rights of private entities to manage their content without government interference. For a remand, this opinion is surprisingly strong – and strong in protection of the First Amendment. Murthy v. Surgeon General: Supreme Court Punts on Social Media Censorship – Alito Pens Fiery Dissent6/26/2024

The expected landmark, decision-of-the-century, Supreme Court opinion on government interaction with social media content moderation and possible official censorship of Americans’ speech ended today not with a bang, not even with a whimper, but with a shrug.

The Justices ruled 6-3 in Murthy v. Missouri to overturn a lower court’s decision that found that the federal government likely violated the First Amendment rights of Missouri, Louisiana, and five individuals whose views were targeted by the government for expressing “misinformation.” The Court’s reasoning, long story short, is that the two states and five individuals lacked Article III standing to bring this suit. The court denied that the individuals could identify traceable past injuries to their speech rights. In short, a case that could have defined the limits of government involvement in speech for the central media of our time was deflected by the court largely on procedural grounds. Justice Samuel Alito, writing a dissent signed by Justices Clarence Thomas and Neil Gorsuch, implicitly criticized this punt, calling Murthy v. Surgeon General “one of the most important free speech cases to reach this Court in years.” He compared the Court’s stance in this case to the recent National Rifle Association v. Vullo, an opinion that boldly protected private speech from government coercion. The dissenters disagreed with the Court on one of the plaintiffs’ standing, finding that Jill Hines, a healthcare activist whose opinions on Covid-19 were blotted out at the request of the government, most definitely had standing to sue. Alito wrote: “If a President dislikes a particular newspaper, he (fortunately) lacks the ability to put the paper out of business. But for Facebook and many other social media platforms, the situation is fundamentally different. They are critically dependent on the protections provided by §230 of the Communications Decency Act of 1996 … For these and other reasons, internet platforms have a powerful incentive to please important federal officials …” We have long argued that when the government wants to weigh in on “misinformation” (and “disinformation” from malicious governments), it must do so publicly. Secret communications from the government to the platforms to take down one post or another is inherently offensive to the Constitution and likely to lead us to a very un-American place. Let us hope that the Court selects a case in which it accepts the standing of the plaintiffs in order to give the government, and our society, a rule to live by. William Schuck writing in a letter-to-the-editor in The Wall Street Journal:

“The world won’t end if Section 230 sunsets, but it’s better to fix it. Any of the following can be done with respect to First Amendment-protected speech, conduct and association: Require moderation to be transparent, fair (viewpoint and source neutral), consistent, and appealable; prohibit censorship and authorize a right of private action for violations; end immunity for censorship and let the legal system work out liability. “In any case, continue immunity for moderation of other activities (defamation, incitement to violence, obscenity, criminality, etc.), and give consumers better ways to screen out information they don’t want. Uphold free speech rather than the prejudices of weak minds.” The House Energy and Commerce Committee recently held a hearing on a bill that would sunset Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act within 18 months. This proposed legislation, introduced by Chair Cathy McMorris Rodgers and Ranking Member Frank Pallone, aims to force Big Tech to collaborate with Congress to establish a new framework for liability. This push to end Section 230 has reopened the debate about the future of online speech and the protections that underpin it.

Section 230 has been a cornerstone of internet freedom, allowing online platforms to host user-generated content without being liable for what their users post. This legal shield has enabled the growth of vibrant online communities, empowered individuals to express themselves freely, and supported small businesses and startups in the digital economy. The bill’s proponents claim that Section 230 has outlived its usefulness and is now contributing to a dangerous online environment. This perspective suggests that without the threat of liability, platforms have little incentive to protect users from predators, drug dealers, and other malicious actors. We acknowledge the problems. But without Section 230, social media platforms would either become overly cautious, censoring a wide range of lawful content to avoid potential lawsuits, or they might avoid moderating content altogether to escape liability. This could lead to a less free and more chaotic internet, contrary to the bill’s intentions. It is especially necessary for social media sites to reveal when they’ve been asked by agents of the FBI and other federal agencies to remove content because it constitutes “disinformation.” When the government makes a request of a highly regulated business, it is not treated by that business as a request. This is government censorship by another name. If the government believes a post is from a foreign troll, or foments dangerous advice, it should log its objection on a public, searchable database. Any changes to Section 230 must carefully balance the need to protect users from harm with the imperative to uphold free speech. Sweeping changes or outright repeal would stifle innovation and silence marginalized voices. Protect The 1st looks forward to further participation in this debate. Facebook’s independent oversight board is now considering whether to recommend labeling the phrase “from the river to the sea” as hate speech. The slogan – often considered antisemitic – serves as a pro-Palestine rallying cry that calls for the creation of a unified Palestinian state throughout what is currently Israeli territory. What would happen to the millions of people who live in Israel today is, post Oct. 7th, the crux of the controversy.

However one feels about that phrase and its prominent, often uninformed, use by courageous keyboard warriors, it is appropriate that any debate about censoring it takes place in the open. This is particularly important for what is still a central social media platform, Facebook. Like X/Twitter, Instagram, and a few other media platforms, Facebook is an important venue for robust public debate. And while these private companies have every First Amendment right to moderate speech on their platforms on their own terms, because of their size and centrality we believe they nonetheless ought to be as open as possible about how they approach content moderation. Like all prominent thought leaders – individuals and companies alike – they can play an important role in reinforcing societal norms on matters of free expression, even if not legally obliged to do so. Still, at the end of the day, it’s their call. And make a call they did. According to the company, Meta analyzed numerous instances of posts using the phrase “from the river to the sea,” finding that they did not violate its policies against “Violence and Incitement,” “Hate Speech” or “Dangerous Organizations and Individuals.” This in contrast with the U.S. House of Representatives, which recently passed a resolution last month, 377-1, condemning the slogan as antisemitic. The House has a right to pass resolutions. But the opinions and sentiments of the government should not inform, and constitutionally cannot control, what we see on our news feeds. Already, we see too many instances of federal influence over social media platforms’ internal decisions, apparently done behind the scenes and always backed by an implied and sometimes expressed threat of coercion for highly regulated tech companies. Such government “censorship by surrogate” is inappropriate and inconsistent with the First Amendment. That’s why Protect the 1st opposes laws in Florida and Texas that would regulate how social media platforms police their own content. It’s simply not the place of government to use its power and influence to pressure private companies to remove posts or tell them how to make editorial choices. In this same spirit, we urge any decisions by Facebook to remove content to be done with full transparency, especially when that content is of a political nature. No law requires this, nor should it, but transparency is a sensible approach that provides clarity to consumers and reformers about societal norms regarding free expression and association. Hats off to Meta for allowing its advisory board to review and to potentially overrule its decision. Sometimes it seems as if the left and the right are in a contest to see which side can be the most illiberal. With each polarity defining the other as a “threat to democracy,” restrictions on political opponents are rationalized away as a necessary act of public hygiene. Recent events in Europe, from Budapest to Brussels, should serve as a warning to Americans who want to use police power to make their opponents shut up.

In December, the U.S. State Department warned that a new Sovereign Defense Authority law in Hungary “can be used to intimidate and punish” Hungarians who disagree with Prime Minister Viktor Orbán and his ruling party. No less an observer than David Pressman, the U.S. ambassador in Budapest, said: “This new state body has unfettered powers to interrogate Hungarians, demand their private documents and utilize the services of Hungary’s intelligence apparatus – all without any judicial oversight or judicial recourse for its targets.” So how are left-leaning critics responding to the rise of the Europe right? By also using intimidation to shut down speech. In Brussels, police in April acted on orders from local authorities by forcibly shutting down a National Conservatism conference. This event, which was to host discussions among European conservative figures, including Prime Minister Orbán and former Brexit champion Nigel Farage, was terminated hours after it began. The cited reasons for the closure included concerns over potential public disorder linked to planned protests. Such a policy, of course, gives protesters pre-emptive veto power over controversial speech, backed by the police. The conference had earlier faced official meddling to prevent the selection of a venue. Initial plans to host the event at the Concert Noble were thwarted due to pressure from the Socialist mayor of Brussels. Subsequently, a booking at the Sofitel hotel in Etterbeek was canceled after local activists alerted that city’s mayor, who pressured the hotel to withdraw its support. Finally, the organizers settled on the Claridge Hotel, only to encounter further challenges including threats to the venue’s owner and logistical disruptions orchestrated by local authorities, culminating in the police blockade that effectively stifled the conference. The good news is public response to the shutdown of the National Conservatism conference was vocal and critical. Belgian Prime Minister Alexander De Croo voiced a strong objection, stating that such bans on political meetings were unequivocally unconstitutional. British Prime Minister Rishi Sunak also responded that canceling events and de-platforming speakers is damaging to democracy. The closure in Brussels is particularly ironic given the city's status as the capital of the European Union, a supposed bastion of liberal democratic values. The forced closure, threats to cut electricity, and the barring of speakers are tactics that betray a fundamental disrespect for democratic norms. What transpired was a scenario more befitting a "tinpot dictatorship," as Frank Füredi, one of the event's organizers, put it. Speech crackdowns seem to be a European disease. This aggressive move to silence a peaceful assembly under the guise of preventing disorder echoes the same illiberal impulses driving Scotland's Hate Crime and Public Order Act. That law broadly criminalizes speech under the expansive banner of “stirring up hatred.” Americans would do well to look to Europe to see what cancellation and criminalization of speech looks like. As the cities and campuses of the United States face what promises to be a hot summer of protest over Gaza, Americans need to keep a relentless focus on protecting speech – even speech one regards as heinous – while preventing tent city invasions, vandalism, and violence that compromises the rights of others. Can a government regulator threaten adverse consequences for banks or financial services firms that do business with a controversial advocacy group like the National Rifle Association? Can FBI agents privately jawbone social media platforms to encourage the removal of a post the government regards as “disinformation”?

As the U.S. Supreme Court considers these questions in NRA v. Vullo and Murthy v. Missouri, a FedSoc Film explores the boundary between a government that informs and one that uses public resources for propaganda or to coerce private speech. (“Nice social media company you have there. Shame if anything happened to it.”) Posted next to this film, Jawboned, on the Federalist Society website is Protect The 1st’s own Erik Jaffe, who in a podcast explores the extent to which the government, using public monies and resources, should be allowed to speak, if at all, on matters of opinion. Is the expenditure of tax dollars to push a favored government viewpoint a violation of the First Amendment rights of Americans who disagree with that view? Jaffe thinks so and argues why this is the logical conclusion of decades of First Amendment jurisprudence. Furthermore, when the government tells a private entity subject to its power or control what the government thinks it ought to be saying (or not saying), Jaffe says, “there’s always an implied ‘or else.’” And even the government’s own public speech often has coercive consequences. As if to underscore this point, Jawboned recounts the story of how the federal Office of Price Administration during World War Two lacked the authority to order companies to reduce prices but did threaten to publicly label them and their executives as “unpatriotic.” That was a very real threat in wartime. Imagine the “or else” sway government has today over highly regulated firms like X, Meta, or Google. In short, Jaffe argues that a line is crossed when “the power and authority of the government” is invoked to use “the power of office to coerce people.” But it also crosses the line when the government uses its resources (funded by compelled taxes and other fees) to amplify its own viewpoint on questions being debated by the public. Such compelled support for viewpoint selective speech violates the freedom of speech of the public in the same way compelled support for private expressive groups and viewpoints does. Click here to listen to more of Erik Jaffe’s thoughts on the limits of government speech and to watch Jawboned. Now that the bill to force the sale of TikTok has passed the U.S. Senate, and its signature by President Biden is certain, Protect The 1st as a First Amendment organization must speak out.

We believe the bill – soon-to-be-law – is reasonable. Many of our fellow civil liberties peers make the valid point that if the government can silence one social media platform, it can close any media outlet, newspaper, website, or TV channel. We would oppose any such move with forceful public protest. But this is a compelled divestiture, which seems like the least restrictive way to protect the speech rights of TikTok’s American users while protecting their data. TikTok’s content is not the issue. The issue is one of ownership and operations. The fundamental problem, of course, and the problem that gave rise to this legislation, is that TikTok is obligated by Chinese law to share all its data with the People’s Liberation Army, the military wing of the Chinese Communist Party. Under President Xi Jinping, Beijing has crushed democracy in Hong Kong, and silenced a newspaper – Apple Daily – while imprisoning its publisher, Jimmy Lai. Xi’s regime also frequently expresses malevolent intentions toward the United States. It arms Russia’s imperialist war to conquer Ukraine, a democracy. And it frequently advertises its own imperialist plan to conquer Taiwan, another democracy. It doesn’t make sense to treat a publication utterly beholden to a regime that shutters newspapers, imprisons publishers, and supports wars on democracies as if it were just another social media platform. Caution is warranted. A crisis between the United States and China is growing increasingly likely. TikTok gives China the means to dig into the private data of 150 million Americans, including families with parents working in the U.S. military, government, and business. To mandate a sale to an owner outside of China would begin the protection of Americans’ data, while allowing TikTok to remain the popular and vivid platform that people enjoy. For more background on this issue, check out this recent PT1st post. Lindke v. Freed The U.S. Supreme Court is set to address several critical free-speech cases this session related to speech rights in the context of social media. One of those questions was recently settled, with the Court ruling on whether an official who blocks a member of the public from their social media account is engaging in a state action or acting as a private citizen. Answer: It depends on the context.

Writing for a unanimous Court in the case of Lindke v. Freed, Justice Amy Coney Barrett reaffirmed that members of the public can sue a public official where their actions are “attributable to the State” (consistent with U.S.C. §1983). In order to make that determination, the Court issued a new test, holding that: “A public official who prevents someone from commenting on the official’s social-media page engages in state action under §1983 only if the official both (1) possessed actual authority to speak on the State’s behalf on a particular matter, and (2) purported to exercise that authority when speaking in the relevant social-media posts.” This is a holistic analysis, consistent with the Protect The 1st amicus brief filed in O’Connor-Ratcliff v. Garnier. We argued that “no single factor is required to establish state action; rather, all relevant factors must be considered together to determine whether an account was operated under color of law.” That case, along with the Court’s banner case, Lindke v. Freed, is now vacated and remanded for new proceedings consistent with the Court’s novel test. When, as the Court acknowledges, “a government official posts about job-related topics on social media, it can be difficult to tell whether the speech is official or private.” So the Court set down rules. A state actor must have the actual authority – traced back to “statute, ordinance, regulation, custom, or usage” – to speak on behalf of the state. However, should an account be clearly designated as “personal,” an official “would be entitled to a heavy (though not irrebuttable) presumption that all of the posts on [their] page were personal.” In Lindke v. Freed, the public official’s Facebook account was neither designated as “personal” nor “official.” Therefore, a fact-specific analysis must be undertaken “in which posts’ content and function are the most important considerations.” As the Court explains: “A post that expressly invokes state authority to make an announcement not available elsewhere is official, while a post that merely repeats or shares otherwise available information is more likely personal. Lest any official lose the right to speak about public affairs in his personal capacity, the plaintiff must show that the official purports to exercise state authority in specific posts.” When a public official blocks a citizen from commenting on any of his posts on a “mixed-use” social media account, he risks liability for those that are professional in nature. Justice Barrett writes that a “public official who fails to keep personal posts in a clearly designated personal account therefore exposes himself to greater potential liability.” It's always been good policy to keep official and private accounts separate. The public must be able to have access to government-issued information, whether through a social media account or a public notice posted on the door of a government building. Moreover, citizens should be able to speak on issues of public concern, whether through Facebook or in a public square. Officials – presidents and former presidents included – should take note. A video depicting a recent interaction between an Oklahoma woman and three FBI agents has become a Rashomon-style meditation on the power of perception, with advocates and activists from across the ideological spectrum drawing their own object lessons from it. Review the video and you will see that the underlying issue at hand is fundamentally about the speech rights of an American citizen.

Here are the facts: Early in the morning of March 19, Rolla Abdeljawad of Stillwater, Oklahoma, answered her front door to find three FBI agents. Their purpose: To discuss some of the Egyptian-American’s Facebook posts. Abdeljawad is critical of Israel’s actions in the Gaza Strip. According to Washington Post, she regularly refers to Israel as “Isra-hell” and calls the Israeli Defense Forces “terrorist filth.” What she has not done is advocate for violence. You may find her posts unfair, but they do not rise to the level of a First Amendment exception, such as a true threat. Abdeljawad proved herself savvy regarding her civil rights. She recorded her interaction with the FBI agents, in which they can be heard claiming that Facebook “gave us a couple of screenshots of your account.” "So we no longer live in a free country, and we can't say what we want?" Abdeljawad responded. “No, we totally do. That's why we're not here to arrest you or anything," replied another agent. “We do this every day, all day long. It's just an effort to keep everybody safe and make sure nobody has any ill will.” (Emphasis added.) The implication here is that the FBI undertakes door-knocking expeditions “every day, all day long” to grill civilians about their protected speech online so no one has “ill will.” If someone is not calling for violence, as is the case here, there is no reason for a visit from the FBI. After all, such a visit by armed agents will never be taken as a benign consultation. It can’t help but have a chilling effect on speech. According to a report from Reason, “Meta's official policy is to hand over Facebook data to U.S. law enforcement in response to a court order, a subpoena, a search warrant, or an emergency situation involving ‘imminent harm to a child or risk of death or serious physical injury to any person.’” Clearly, judging from Abdeljawad’s encounter with the FBI, that policy can be misconstrued or ignored entirely. Law enforcement should never be harassing rank-and-file citizens over protected speech. Abdeljawad’s lawyer, Hassan Shibly, posted the video of the interaction across platforms with some good advice for others who may find themselves with unwanted visitors with FBI badges and spurious questions:

Americans should not accept as routine government agents coming to our homes to question us about opinions they find abrasive. There is no federal bureau of civil discourse, nor should there be in a First Amendment society. The recent House passage of a bill to force the sale of TikTok from its Chinese parent company – or suffer an outright ban – triggers obvious questions about the First Amendment. Many of our fellow civil liberties organizations have come to TikTok’s defense, making the point that if the government can silence one social media platform, it can close any media outlet, newspaper, website, or TV channel.

They point to many of TikTok’s strongest critics, who accuse it of pushing China’s line on sensitive issues and dividing Americans in what promises to be an especially heated election season. But our civil liberties allies remind us that the First Amendment protects all speech, no matter how divisive, even if it echoes foreign propaganda. That is fine as far as it goes, but there are other issues beyond the First Amendment in the TikTok debate. Here is where we break ranks with some of our peers: We see real danger in TikTok’s accumulation of the personal data of its 150 million American users, and 67 percent of U.S. teens – and how TikTok’s influence could harm the First Amendment by threatening the freedom of the press and the speech of users. After reviewing results from a year-long, bipartisan investigation, the House concluded that TikTok is being used by Beijing to spy on American citizens. TikTok’s parent company, ByteDance, has had a notorious relationship with the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). As we wrote last year, the Department of Justice and FBI have been investigating ByteDance over CCP access to Americans’ data. According to Emily Baker-White, a Forbes reporter who was herself surveilled by ByteDance, the department and U.S. Attorney for the Eastern District of Virginia have hit the Chinese firm with subpoenas about its purported surveillance of U.S. journalists. The company’s data policies have led multiple states to ban the app on state employee devices. It would be a flagrant violation to ban a newspaper for its content. But what if a hostile power deliberately manufactured newspapers with arsenic dye, toxic to the touch? In such a case, First Amendment issues would be irrelevant. ByteDance is compelled by Chinese law to share all its data with the Beijing government, and its military and intelligence agencies. Senators should determine whether the toxicity of the threats posed by TikTok's data practices and its relationship with the CCP necessitate action. This is not the first time the United States has forced a Chinese company to divest a social media platform. In 2020, the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States raised the alarm about Kunlun Tech’s acquisition of Grindr, a popular LGBTQ dating app. The app already had a poor reputation for data security, but the committee was reportedly worried that the Chinese government could use personal data from the app to blackmail U.S. citizens, including government officials. The committee gave Kunlun a deadline by which it had to sell Grindr, and the app was sold back to an American owner. Forcing a media outlet to sell or go out of business is a drastic action, not to be undertaken lightly. But as the Senate debates, we should keep in mind that there are issues at stake in the TikTok controversy that go beyond the First Amendment. The U.S. Supreme Court heard oral arguments Monday in Murthy v. Missouri, a case addressing the government's covert efforts to influence social media content moderation during the Covid-19 pandemic. Under pressure from federal and state actors, social media companies reportedly engaged in widespread censorship of disfavored opinions, including those of medical professionals commenting within their areas of expertise.

The case arose when Missouri and Louisiana filed suit against the federal government arguing that the Biden Administration pressured social media companies to censor certain views. In reply, the government responded that it only requested, not pressured or demanded, that social media companies comply. Brian Fletcher, U.S. Principal Deputy Solicitor General, told the Court it should “reaffirm that government speech crosses the line into coercion only if, viewed objectively, it conveys a threat of adverse government action.” This argument seems reasonable, but a call from a federal agency or the White House is not just any request. When one is pulled over by a police officer, even if the conversation is nothing but a cordial reminder to get a car inspected, the interaction is not voluntarily. Social media companies are large players, and an interaction with federal officials is enough to whip up fears of investigations, regulations, or lawsuits. In Murthy v. Missouri, it just so happens that the calls from federal officials were not just mere requests. According to Benjamin Aguiñaga, Louisiana’s Solicitor General, “as the Fifth Circuit put it, the record reveals unrelenting pressure by the government to coerce social media platforms to suppress the speech of millions of Americans. The District Court which analyzed this record for a year, described it as arguably the most massive attack against free speech in American history, including the censorship of renowned scientists opining in their areas of expertise.” At the heart of Murthy v. Missouri lies a fundamental question: How far can the government go in influencing social media's handling of public health misinformation without infringing on free speech? Public health is a valid interest of the government, but that can never serve as a pretense to crush our fundamental rights. When pressure to moderate speech is exerted behind the scenes – as it was by 80 FBI agents secretly advising platforms what to remove – that can only be called censorship. Transparency is the missing link in the government's current approach. Publicly contesting misinformation, rather than quietly directing social media platforms to act, respects both the public's intelligence and the principle of free expression. The government's role should be clear and open, fostering an environment where informed decisions are made in the public arena. Perhaps the government should take a page from Ben Franklin’s book (H/T Jeff Neal): “when Men differ in Opinion, both Sides ought equally to have the Advantage of being heard by the Publick; and that when Truth and Error have fair Play, the former is always an overmatch for the latter …” Protect The 1st looks forward to further developments in this case. Noted fraudster former Rep. George Santos made headlines last week when he sued television personality Jimmy Kimmel for – what else? – fraud after Kimmel broadcasted a series of 14 personalized Cameo videos he requested from the disgraced former congressman. It “may be the most preposterous lawsuit of all time,” said Kimmel. Yet, ironically, Santos’ former colleagues in Congress could soon be the ones to legitimize Santos’ claims.

Santos, expelled from Congress for a range of misdeeds including stealing from campaign donors and money laundering, is perhaps as ripe a target for satire as can be found in our astonishingly silly and self-centered era. Santos, days after being removed from the U.S. House of Representatives joined Cameo, a video service where B-list celebrities record personalized messages for a few hundred bucks a pop ($500 in Santos’ case), providing catnip for comedians. The No AI FRAUD Act now under consideration in Congress could make comedy a crime, or at least a tort. To be fair, the bill does address a real concern: it is intended to protect “Americans’ individual right to their likeness and voice,” providing actors, celebrities, and others the means to safeguard their image. But it is overbroad in addressing the pitfalls of artificial intelligence, an issue that has captured the minds – and anxieties – of lawmakers across the country. This bill would create a federal right to a digital “replica” akin to a right of publicity, recognized under many state laws. It would allow a plaintiff to sue for commercial misappropriation of one’s likeness or voice. As written, the bill would “restrict a range of content wide enough to ensnare parody videos, comedic impressions, political cartoons, and much more” (H/T Reason). Sponsors, Reps. María Elvira Salazar (R-Fla.) and Madeleine Dean (D-Pa.), are right to be concerned about AI-generated fakes and forgeries, as we saw in the recent AI fake of President Biden’s voice during the New Hampshire primary. But their bill is overbroad, capturing all manner of media representations currently protected by the First Amendment. Specifically, it prohibits any “replica, imitation, or approximation of the likeness of an individual that is created or altered in whole or part using digital technology.” That means an “actual or simulated image … regardless of the means of creation, that is readily identifiable as the individual.” Read this again – any imitation of an individual created by digital technology. Such a law could cover photos, recordings, parodies – even political cartoons. To quote Reason’s Elizabeth Nolan Brown, “if it involved recording or portraying a human, it’s probably covered.” A host of organizations have spoken out on the “No AI FRAUD Act,” including the Motion Picture Association, which argues that the creation of a digital “replica” right would “constitute a content-based restriction on speech.” As the Motion Picture Association wrote in a letter to Congress, “the government has no compelling interest in restricting creative depictions of public figures (including performers) in stories about them or the world they inhabit.” Congress should find ways to protect actors from having their image and career exploited without permission. This can be done without the chilling effects on artistic forms of expression, especially comedy and commentary. Doing so will require a nuanced and well-articulated bill. As it stands, the bill’s prohibitions are decidedly not funny. They could encompass sketch comedy, impressions, cartoons depicting real-life persona, or depictions of historical figures. As the Electronic Frontier Foundation wrote, “there’s not much that wouldn’t fall into [the category of prohibitions]—from pictures of your kid, to recordings of political events, to docudramas, parodies, political cartoons, and more. If it involved recording or portraying a human, it’s probably covered.” We need a sewing needle – not a hammer – to develop nuanced AI prohibitions that are consistent with the First Amendment. A bill that reads like it originated from a ChatGPT query doesn’t cut it. The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit recently heard oral arguments in the case of Volokh v. James. It’s another in a series of critical recent cases involving government regulation of online speech – and one the Empire State should ultimately lose.

In 2022, distinguished legal scholar and Protect The 1st Senior Legal Advisor Eugene Volokh – along with social media platforms Rumble and Locals – brought suit against the state of New York after it passed a law prohibiting “hateful” conduct (or speech) online. Specifically, the law prohibits “the use of a social media network to vilify, humiliate, or incite violence against a group or a class of persons on the basis of race, color, religion, ethnicity, national origin, disability, sex, sexual orientation, gender identity or gender expression.” The law also requires platforms to develop and publish a policy laying out how exactly they will respond to such forms of online expression, as well as to create a complaint process for users to report objectionable content falling within the boundaries of New York’s (vague and imprecise) prohibitions. Should they fail to comply, websites could face fines of up to $1,000 per day. There are a number of problems with New York’s bid to regulate online speech – not least of which is that there is no hate speech exception to the First Amendment. As the Supreme Court noted in Matal v. Tam, “speech that demeans on the basis of race, ethnicity, gender, religion, age, disability, or any other similar ground is hateful; but the proudest boast of our free speech jurisprudence is that we protect the freedom to express ‘the thought that we hate.’” Moreover, the law fails to define key terms like “vilify,” “humiliate,” or “incite” – leaving its interpretation up to the eye of the beholder. As Volokh explained in a piece for Reason, “it targets speech that could simply be perceived by someone, somewhere, at some point in time, to vilify or humiliate, rendering the law's scope entirely subjective.” Does an atheist’s post criticizing religion “vilify” people of faith? Does a video of John Oliver making fun of the British monarchy “humiliate” the British people? The hypotheticals are endless because one’s subjective interpretation of another’s speech could cut a million different ways. In February 2023, a district court ruled against New York, broadly agreeing with Volokh’s arguments. As Judge Andrew L. Carter, Jr. wrote: “The Hateful Conduct Law both compels social media networks to speak about the contours of hate speech and chills the constitutionally protected speech of social media users, without articulating a compelling governmental interest or ensuring that the law is narrowly tailored to that goal.” To be fair, there is a purported government interest at play here, even if it’s not compelling in the broader context of the law’s vast, unconstitutional reach. The New York law is a legislative response to a 2022 Buffalo supermarket shooting perpetrated by a white supremacist who was, by all accounts, steeped in an online, racist milieu. Every decent person wants to give extremist views no oxygen. But incitement to violence is already a well-established First Amendment exception – unprotected by the law. Broadly compelling websites to create processes for addressing subjective, individualized offenses simply goes too far. Anticipating New York’s appeal to the Second Circuit, a number of ideologically disparate organizations joined with the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression, or FIRE, (which is prosecuting the case), submitting amicus curiae briefs in solidarity with Volokh and his co-plaintiffs. Those groups – which include the American Civil Liberties Union, the Electronic Frontier Foundation, the Cato Institute, and satirical website the Babylon Bee – stand in uncommon solidarity against the proposition that government should ever be involved in private content moderation policies. As the ACLU and EFF assert, "government interjection of itself into that process in any form raises serious First Amendment, and broader human rights, concerns." True to form, the Babylon Bee’s brief notes that “New York's Online Hate Speech Law would be laughable – if its consequences weren't so serious.” When the U.S. Supreme Court renders its opinion on the Texas and Florida social media laws, it will give legislatures a better guide to developing more precise, articulable means of addressing online content. When does a legal reporting requirement for a social media company become a violation of the First Amendment? When it drums up public and political pressure to enforce viewpoint discrimination.

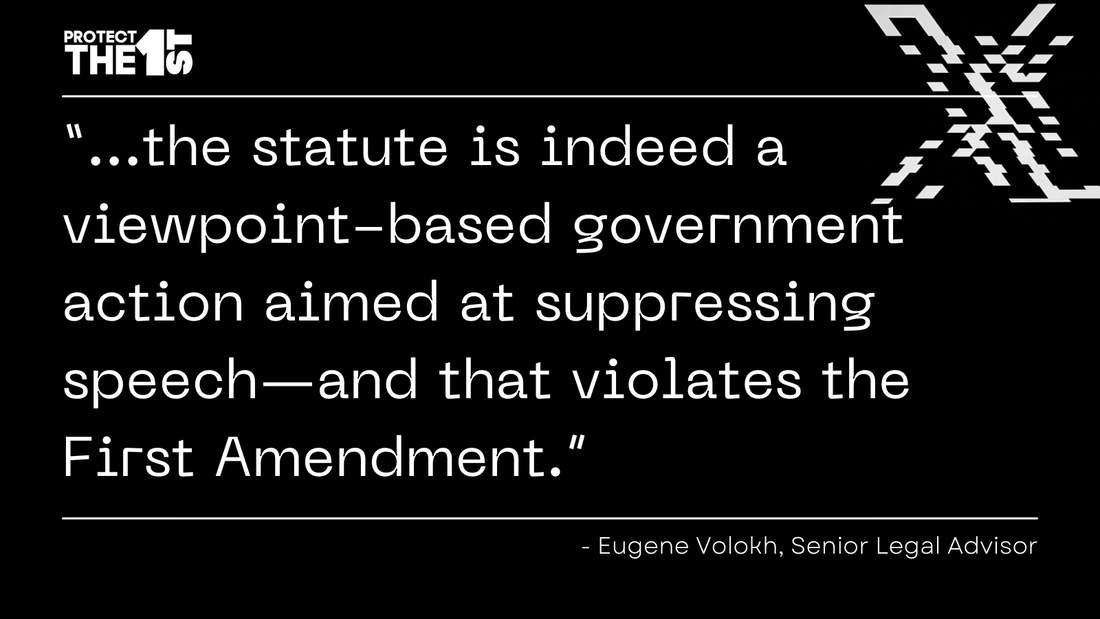

This is the conclusion of legal scholar Eugene Volokh and Protect The First Foundation, which filed an amicus brief late Wednesday before the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals asking it to overturn a lower court ruling that upheld a California law requiring social media companies to disclose their content moderation practices. California Bill AB 587, signed into law by Gov. Gavin Newsom in 2022, compels social media companies to produce two such reports a year on their moderation practices and decisions, to be published on the website of the California Attorney General. This law “violates the First Amendment’s stringent prohibition on viewpoint discrimination” by “requiring social media companies to define viewpoint-based categories of speech,” declared Volokh, Senior Legal Advisor to Protect The 1st. “The law also requires these companies to report their policies as to those viewpoints, but not other viewpoints ...” This brief supports the challenge from X Corp.’s lawsuit filed in September 2023 that also asserted that AB 587 violates the First Amendment, which “unequivocally prohibits this kind of interference with a traditional publisher’s editorial judgment.” Volokh and Protect The 1st cited the landmark U.S. Supreme Court case, NAACP v. Alabama (1958), in which the Court overturned an Alabama law that would have compelled disclosure of the NAACP’s membership lists. The threat behind this law, the Court noted, relied on governmental and private community pressures that would result in the harassment of individuals and discouragement of their speech. “Generating either massive fines or public ‘pressure,’ a euphemism for public hostility, triggers the most exacting scrutiny our Constitution demands,” Volokh told the court. “California Assembly Bill 587 violates the First Amendment’s stringent prohibition on viewpoint discrimination. And AB 587 does so by leaning on social media companies to do the government’s dirty work, either through fear of fine or public pressure.” The brief cites a Supreme Court opinion that states “what cannot be done directly [under the Constitution] cannot be done indirectly.” Volokh writes: “The intent behind the law is clear from its legislative history, comments by its enforcer (Attorney General Rob Bonta), and common sense. That intent is to strongarm social media companies to restrict certain viewpoints—to combine law and public pressure to do something about how platforms treat those particular viewpoints, and not other viewpoints. That confirms that the facial viewpoint classification in the statute is indeed a viewpoint-based government action aimed at suppressing speech—and that violates the First Amendment.” Protect The 1st will continue to report on X Corp.v. Bonta as an important flashpoint in the continuous struggle to keep speech free of official regulation. Should we move to a post-Section 230 internet? Is liability-free content hosting coming to an end?

In Wired, Jaron Lanier and Allison Stanger argue for ending that provision of the Communications Decency Act that protects social media platforms from liability over the content of third-party posts. The two have penned a thoughtful and entertaining analysis about the problems and trajectory of a Section 230-based internet. It’s worth reading but takes its conclusions to an unjustifiable extreme – with unexamined consequences. The authors assert that while Section 230 may have served us well for a time, they argue that long-running negative trends have outpaced the benefits that Section 230 provided. The authors write that modern, 230-protected algorithms heavily influence the promotion of lies and inflammatory speech online, which it obviously does. “People cannot simply speak for themselves, for there is always a mysterious algorithm in the room that has independently set the volume of the speaker’s voice,” Lanier and Stanger write. “If one is to be heard, one must speak in part to one’s human audience, in part to the algorithm.” They argue algorithms and the “advertising” business model appeal to the most primal elements of the human brain, effectively capturing engagement by promoting the most tantalizing content. “We have learned that humans are most engaged, at least from an algorithm’s point of view, by rapid-fire emotions related to fight-or-flight responses and other high-stakes interactions.” This dynamic has had enormous downstream consequences for politics and society; Section 230 “has inadvertently rendered impossible deliberation between citizens who are supposed to be equal before the law. Perverse incentives promote cranky speech, which effectively suppresses thoughtful speech.” All this has led to a roundabout form of censorship, where arbitrary rules, doxing, and cancel culture stifle speech. Lanier and Stanger call this iteration of the internet the “sewer of least-common-denominator content that holds human attention but does not bring out the best in us.” Lanier and Stanger offer valid criticisms of the current state of the net. It is undeniable that discourse has coarsened in connection with the rise of social media platforms and toxic algorithms. Worse, the authors are correct that algorithms provide an incentive for the spreading of lies about people and institutions. Writing that John Smith is a lying SOB who takes bribes will, to paraphrase Twain, pull in a million “likes” around the world before John Smith can tie his shoes. So what is to be done? First, do not throw out Section 230 in toto. As we previously said in our brief before the U.S. Supreme Court with former Senator Rick Santorum, gutting Section 230 “would cripple the free speech and association that the internet currently fosters.” Without immunity, internet platforms could not organize content in a way that would be relevant and interesting to users. Without Section 230 protections, media platforms would avoid nearly any controversial content if they could be frivolously sued anytime someone got offended. Second, do consider modifications of Section 230 to reduce the algorithmic incentives that fling and spread libels and proven falsehoods. Lanier and Stanger make the point that the current online incentives are so abusive that the unhinged curtail the free speech of the hinged. We should explore ways to reduce the gasoline-pouring tendency of social media algorithms without impinging on speech. Further reform might be along the lines of the bipartisan Internet PACT Act, which requires platforms to have clear and transparent standards in content moderation, and redress for people and organizations who have been unfairly deposted, deplatformed, and demonetized. Lanier and Stanger are thinking hard and honestly about real problems, but the problems they would create would be much worse. A post-230 social media platform would be either be curated to the point of being inane, or not curated at all. Now that would be a sewer. Still, we give Lanier and Stanger credit for stimulating thought. Everyone agrees something needs to change online to promote more constructive dialogue. Perhaps we are getting closer to realizing what that change should be. Woman Arrested for Social Media Snark While High Court Protects Suspect’s Right to Tell Police to “Worry About a Head Shot”A woman in Morris County, New Jersey, was arrested in December for her social media posts that officials say constituted threats of terrorism, harassment, and retaliation. The last two of those “threats” seem to pertain to the authorities, who stretched statements from the merely obnoxious to appear as a “true threat.”

Monica Ciardi had been posting to Facebook for weeks about her child custody dispute. Her posts, coming by the dozens, criticized her ex-husband and the Morris County judges presiding over her case. In late December, police finally arrested Ciardi for posting “Judge Bogaard and Judge DeMarzo: If you don’t do what I want then you don’t get to see your kids. Hmm.” Here’s the catch, Ciardi was parroting what the two judges said to her, accidentally forgetting to use quotation marks. Ciardi had meant to post what the judges had declared in court – that if she didn’t do what they wanted, then she wouldn’t get to see her children. Ciardi offered an insightful metaphor: “This is my personal Facebook page with 50 people on it. They came to my page and then turned around and said I harassed them. That’s like if I know you don’t like me, I go to your house, I stand on your front porch, I overhear you saying bad things about me, and then I call the cops and say, ‘She’s harassing me. I know I’m on her porch, but you should just hear what she said.'” Ciardi’s attorney said the incident amounted to “the government punishing and jailing a woman for simply speaking her mind.” Ciardi claims her experience in jail was a nightmare. While there, she says that she received death threats, saw several assaults, and got caught in the line of fire of correctional officers’ pepper spray twice. She says she suffered panic attacks, lost 15 pounds, and was placed in protective custody, which meant she didn’t leave her cell “for more than 45 minutes two to three times a week, max.” That’s stiff punishment for venting frustrations online. Ciardi spent 35 days in jail until Superior Court Judge Mark Ali, who had originally ordered her detention, ordered her release. Ali cited a recent New Jersey Supreme Court ruling that raised the bar for terroristic threat charges. That case, too, is problematic, but for the opposite reason. Even a First Amendment organization like our own is agog at that ruling. The New Jersey high court ruled on Jan. 16 that a man who told police during a domestic disturbance call to “worry about a head shot” if they enter his property. He also posted online that he knew where the officers lived and the cars they drove. The court ruled that prosecutors had failed to prove that such statements were credible threats that “instill fear of injury in a reasonable person in the victim’s position” and are not merely “political dissent or angry hyperbole.” While we are pleased to see that Ciardi has been released, we disagree with the New Jersey court’s new precedent. In the case of the “head shot,” the threat was made against the putative target, the police. Unless the comment was made in an obviously sarcastic way or in some manner that indicated its insincerity, law enforcement should be able to take such claims seriously. There must be an easy line to be drawn between arresting a woman for her Facebook posts about a pending trial and a true threat of violence against law enforcement officers. We look forward to further developments in this latest case. In the closing days of 2023, Elon Musk and X Corp lost the first round of their bid in a state court to overturn a California law that would require social media platforms to disclose their content moderation policies. The law in question came into effect in 2022 and was advertised as a way to tamp down on hate speech, disinformation, harassment, and extremism.

The suit alleged that that the law’s real purpose was to coerce social media platforms into censoring content deemed problematic by the state. While District Judge William Shubb ruled that the law does impose a substantial compliance burden, he found it does not unjustifiably infringe on First Amendment rights. Protect The 1st believes X has a strong basis to appeal under settled precedent. For example, in Zauderer v. Office of Disciplinary Counsel of Supreme Court of Ohio (1985), the U.S. Supreme Court found that states can require an advertiser to disclose information without violating the advertiser's First Amendment free speech protections. But the disclosure requirements must be reasonably related to the state’s interest in preventing deception of consumers. This is not a case of selling gummies and advertising them as cures for cancer. It is reasonable to assert that some social media companies might do themselves a favor by releasing simple, clear content moderation policies to the public. But we should never forget that these policies are confidential, proprietary information. Requiring their forced disclosure could tip the scales in favor of state-enforced censorship of social media, which at least one federal judge believes is already occurring on a mass scale. Worse, the California law violates the First Amendment by compelling speech on the part of the companies themselves. Protect The 1st expects X to appeal with good prospects to overturn this ruling. Censorship controversies made many headlines throughout 2023. We’ve seen revelations about heavy-handed content moderation by the government and social media companies, and the looming U.S. Supreme Court decisions on Florida and Texas laws to restrict social media. Behind these policies and laws is a surprising level of public support. A Pew Research poll offers a skeleton key for understanding the trend.

According to Pew, a majority of Americans now believe that the government and technology companies should make more concerted efforts to restrict false information online. Fifty-five percent of Pew respondents support the federal government removal of false information, up from only 39 percent in 2018. Some 65 percent of respondents support tech companies editing the false information flow, up from 56 percent in 2018. Most alarming of all, Americans adults are now more likely to value content moderation over freedom of information. In 2018, that preference was flipped, with Americans more inclined to prioritize freedom of information over restricting false information – 58 percent vs. 39 percent. Pew doesn’t editorialize when it posts its findings. For our part, these results reveal a disturbing slide in Americans’ appreciation for First Amendment principles. Online “noise” from social media trolls is annoying, to be sure, but sacrificing freedom of information for a reduction in bad information is anathema to the very notion of a free exchange of ideas. What is needed, instead, is better media literacy – not to mention a better understanding of what actually constitutes false information, as opposed to opinions with which one may simply disagree. Still, the poll goes a long way toward explaining some of the perplexing attitudes we’re seeing on college campuses, where polls show college students lack a basic understanding of the First Amendment and increasingly support the heckler’s veto. These poll results also speak to the increasing predilection of public officials to simply block constituents with whom they disagree. And it perhaps explains some of the push-and-pull we’re seeing between big, blue social media platforms and big, red states like Florida and Texas, where one side purports to protect free speech by infringing on the speech rights of others. While these results are interesting from an academic perspective, the suggested remedies raise major red flags. Americans want private technology companies to be the arbiters of truth. A lesser but still significant percentage wants the federal government to serve that role. Any institution comprised of human beings is bound to fail at such a task. Ultimately, if we want to protect the free exchange of information, that role must necessarily fall to each of us as discerning consumers of news. The extent to which we are unable to differentiate between factual and false information is an indictment of our educational system. And, as far as content moderation policies are concerned, they must be clear, standardized, and include some form of due process for those subjected to censorship decisions. More than anything, Americans need to relearn that if we open the door to a private or public sector “Ministry of Truth,” we will eviscerate the First Amendment as we know it. You might be on the winning side initially, but eventually we all lose. A federal judge in Texas has upheld the state’s TikTok ban on devices used for government business. It’s the right ruling – a correct response to a precise law which undergirds the state’s legitimate interest in prohibiting the use of a potentially harmful social media app in official settings.

TikTok is a Chinese company with user data stored on servers in the PRC. It holds inordinate sway over young people in the US, with 67% of teens using the platform with some regularity, according to Pew. Yet, there is now credible public evidence that China’s officials enjoy open access to personal data on the platform, using it to spy on pro-democracy protestors. An employee of ByteDance, the corporate owner of TikTok, has made that claim. The Coalition for Independent Technology Research filed the lawsuit in July, arguing that the Texas ban compromises academic freedom. One teacher from the University of North Texas even suggested that they cannot sufficiently assign work without use of the app. Texas’ law specifically disallows the use of TikTok on state-owned, official devices. That’s in contrast to Montana’s outright ban on the app – for everyone. There, U.S. District Judge Molloy asserted that Montana’s law infringed on free speech rights and exceeded the bounds of state authority. He was right, too, and it was a significant affirmation of the importance of safeguarding fundamental rights in the digital age, particularly within the context of online platforms that serve as crucial arenas for expression. This court split exemplifies the balance we must strike between protecting user freedoms and enabling a safe digital environment without compromising free expression. States have every right to prohibit use of a foreign-controlled app on government owned phones. At the same time, blanket banning of TikTok is neither a constitutional nor reasonable response. Americans can speak freely and freely associate, even if they are unaware of the implications in doing so. State officials and employees, by contrast, are subject to different rules. But they are welcome to use TikTok on their personal phones. As Judge Robert L. Pitman correctly asserts, state universities constitute a “non-public” forum – the touchstone of which is whether “[restrictions] are reasonable in light of the purpose which the forum at issue serves.” Here, “Texas is providing a restriction on state-owned and -managed devices, which constitute property under Texas’s governmental control….” It is both viewpoint neutral and reasonable – which is all that is needed in such cases. Whether TikTok itself is viewpoint neutral is a question for another day. PruneYard Shopping: Are the Speech Rights of Shopping Centers Really Like Those of Social Media?12/19/2023

The Cato Institute’s recent amicus brief making the case that social media laws passed by the states of Texas and Florida are unconstitutional also takes aim at a precedent from 1980, PruneYard Shopping Center v. Robins. Cato’s brief raises the question: Does it make sense to analogize the speech rights of those who own a physical property with those who own a social media company?

In PruneYard, the U.S. Supreme Court held that the California Constitution protected reasonably exercised speech on the privately owned PruneYard shopping center against the owner’s wishes. The Court noted the California Constitution has broader protections for speech than the Bill of Rights. The Court correctly reasoned that states can have greater and positive protections for speech than the negatively defined rights of the First Amendment, which forbids government censorship and curtailments of speech rights. Based on this singular insight, the Court’s opinion established that the shopping center could not prevent outsiders from protesting or soliciting for political purposes on its private property. In its brief, Cato argues that the Supreme Court should at the proper time address this odd ruling and hold that forcing private property owners to accommodate on their premises speech they do not support is a violation of the property owners’ First Amendment rights. Cato also argues that social media platforms should similarly be protected from being forced to carry the speech of others. While Protect The 1st agrees with Cato that the Texas and Florida laws are unconstitutional, the analogy to PruneYard is flawed. Cato’s comparison with real property, however, remains useful, offering an illuminating look at what is unique about social media. As Protect The 1st previously reported, the Florida law would prohibit social media platforms from removing the posts of political candidates, while the Texas law would bar companies from removing posts based on a poster’s political ideology. The former law was struck down by the Eleventh Circuit, while the latter was upheld by the Fifth Circuit. Both cases are now headed to what promises to be a landmark digital speech review by the Supreme Court. But is the extension of the critiques of the PruneYard applicable to social media? This seems inapt because property owners who allow outsiders to mount politically-charged events on their premises might face liability for that speech, just as newspapers can be sued for speech contained in letters-to-the-editor. Social media is different. Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act is a government grant of immunity to social media platforms for third-party speech, while allowing some discretion for the platforms to moderate content. Despite frustrations over actual content management by social media companies, and government involvement in it, Section 230 has allowed a thriving online world to develop – along, of course, with all the attendant psychic garbage. This is utterly unlike shopping centers, which don’t enjoy any such government immunity and could be held legally accountable for the speech that occurs on their property. The two state laws have obvious First Amendment flaws and striking them down doesn’t require revising precedents. The authors of the Texas and Florida laws, concerned about the manipulation of the online debate, would further intrude government meddling into social media content moderation. This power would likely extend far beyond what these politicians imagine (and perhaps even to their specific detriment). We suggest the Supreme Court take a more straightforward analysis of the Florida and Texas laws as it invalidates them under the First Amendment. U.S. District Judge Donald Molloy recently blocked Montana's ban of the Chinese-owned social media platform TikTok, standing up for free speech but leaving a host of issues for policymakers to resolve. Montana’s ban, which was slated to take effect at the beginning of 2024, made it the first U.S. state to take such a measure against the popular video sharing app.