|

Harvard University canceled its invitation to a feminist philosopher who was prepared to talk on British romanticism because she had, in her other writings, expressed disagreement with the tenets of transgender ideology that prevail in academia.

Dr. Devin Buckley had asserted that sex is immutable and that the inclusion of transgender women in women’s sports violates “fair play on sports teams.” Dr. Buckley also questioned the growing practice of putting transgendered females in women’s prisons. For such atrocities, she was cancelled by Erin Saladin, coordinator of the Harvard English Department, who “found at least one piece of her writing online that explicitly denies the possibility of trans identity.” Whatever one’s views on the psychological and social reality of transgenderism, the cancelling of scholars like Dr. Buckley – or the exclusion of celebrity writer J.K. Rowling from Harry Potter events – will not settle any questions or win over hearts and minds. The views in the Harvard English Department notwithstanding, the statements of Buckley and Rowling are hardly outside of the mainstream of public opinion. “I have never written anything hateful towards any transgender individual,” Dr. Buckley told National Review. “I’ve been shunned and ostracized by people at my graduate program. I’ve had people walk down the street refusing to acknowledge that I exist in ritualized shunning and social cancellation.” The same First Amendment that protects Dr. Buckley’s speech also protects Harvard’s right to disinvite her. But a robust culture of speech rests not just on legal protections, but also on a willingness to engage those with whom we disagree. Harvard is poorer for its unwillingness to engage contrary views. As for Dr. Buckley, she says, “For my part, I’d rather be damned with the Romantics and Plato than go to woke heaven with Erin and the Harvard faculty.” Whether one agrees with her sentiment or not, there’s no denying that the Harvard educational experience is diminished when people with her views are denied the opportunity to share them. Coach Kennedy v. Bremerton School DistricT Joe Kennedy – the “praying coach” fired by the Bremerton, Washington, school district for praying on the 50-yard-line after games were concluded – enjoyed mostly friendly questioning in oral argument before the U.S. Supreme Court today.

Justices Samuel Alito, Neil Gorsuch, Clarence Thomas and Brett Kavanaugh all framed most of their questions in terms sympathetic to Coach Kennedy. Given the record of Justice Amy Coney Barrett of support for religious expression, some long-time observers of the Court predicted today’s hearing suggests an eventual 6-3 ruling in favor of upholding the coach’s prayer as a legitimate and private expression of faith by a government employee. The school district had argued that athletes could feel pressure to participate in prayers with a coach who decides who plays and who does not. “We’re worried that the students will feel he gets to put me into a football game, or not,” said Justice Elena Kagan to Kennedy’s lawyer. But the school district’s contention that Coach Kennedy made a spectacle of his prayer was knocked down by Justice Brett Kavanaugh, who questioned the practicality of drawing a line around private prayer that must not draw anyone’s attention. The assertion by the school district’s lawyers that Kennedy’s actions amounted to government speech, however, fell flattest of all. The tenor of the Justices’ questioning echoed the brief filed by Protect the 1st, which offered many examples of how far the First Amendment’s prohibition of “no establishment of religion” can go with a government employee before violating that same amendment’s promise to protect the free exercise of religion. In the brief of our legal arm, the Protect the First Foundation, we noted that government employees, including teachers, often wear religious garments and undertake short, devotional expressions of faith at work without violating policy. Native Americans wear eagle feathers, Christians show up to work on Ash Wednesday with a smudge on their foreheads, Muslim women wear headscarves, Jewish and Muslim men wear prayer caps. A teacher who is Christian might say grace before lunch. A Muslim teacher might pray during a break between classes. All these actions are routine expressions of private faith that do not in any way constitute government speech. Taken literally, a strict effort to block out all such religious characteristics of government employees would quickly turn oppressive. Based on today’s oral argument, Protect The 1st is optimistic the court will see that expressions of faith by public employees deserve protection. Is speech that produces emotional injury a form of stalking? Or is speech – private speech about deeply personal matters – protected by the Constitution? The latter is the case Protect the First Foundation made before the District of Columbia Court of Appeals in a highly charged case about accusations of adultery in the workplace.

It all began when a Washington, D.C., executive, received an email from a distraught husband accusing him of having had an affair with his wife when she worked at his firm as an intern. Messages were sent by email and Facebook to the executive’s network of coworkers, family and friends. Public shaming in the digital age can be robust, vivid, instantaneous and comprehensive. But is it cause for a civil protection order? Protect the First Foundation is asking the District of Columbia’s highest court to revisit the implications of a judgment upholding a D.C. stalking statute that defines it as a crime to “directly or indirectly … in person or by any means, on two or more occasions” to communicate “about another individual” where the speaker “should have known” that such communications would cause “significant mental suffering or distress.” The D.C. law does include exceptions for constitutionally protected speech, such as protests. Thus, the depraved people who inflict emotional distress on the relatives of fallen soldiers at funerals – or neo-Nazis who parade through neighborhoods of elderly Holocaust victims and their descendants – are exercising protected speech. But people who talk trash about someone are not? If rigorously enforced, the District of Columbia might have to slap a civil order on most of its adult citizens. For those who continue to defy the law, perhaps their internment could define a new use for RFK Stadium. Fortunately, precedent points to a different conclusion. In our brief, we noted that the Supreme Court made clear in Engquist v. Oregon Dep’t Agric (2008) that government cannot “generally prohibit or punish, in its capacity as sovereign, speech on the grounds that it does not touch upon matters of public concern.” Well established First Amendment exceptions remain for libel, threats, or obscenity. But an aggrieved husband has First Amendment rights courts are bound to respect at least as much as neo-Nazis and funeral disrupters. Jonathan Yardley, former book critic of The Washington Post, defined the kernel of the issue: “The trouble with free speech is that it insists on living up to its name.” City of Austin, Texas v. Reagan National AdvertisingEven in this digital age, signage remains prominent as a form of speech. In City of Austin, Texas v. Reagan National Advertising, the question before the U.S. Supreme Court was whether a city ordinance forbidding “off-premises” signs was an infringement of the First Amendment.

Protect The First Foundation made the case in an amicus brief that Austin’s prohibition of messages that advertise “a business, person, activity, goods, products, or services not located where the sign was installed” is inherently a regulation of content. A Supreme Court 5-4 majority today disagreed, narrowing the scope of First Amendment protection for billboards and similar signs. The Court’s reasoning seems straightforward. Writing for the majority, Justice Sonia Sotomayor declared that the distinction in location is “agnostic as to content” and is therefore constitutional. “Rather, the City’s provisions distinguish based on location: A given sign is treated differently based solely on whether it is located on the same premises as the thing being discussed or not.” The majority reasons that if a regulation is based on a sufficiently general or broad category, it is not actually content based. Justice Clarence Thomas, with Justices Gorsuch and Barrett, wrote an eloquent dissent: “Under Reed, Austin’s off-premises restriction is content based. It discriminates against certain signs based on the message they convey--e.g., whether they promote an on- or off-site event, activity, or service.” Justice Thomas wrote that the majority ignored the Reed precedent’s “rule for content- based restrictions and replaces it with an incoherent and malleable standard.” Justice Thomas then offered this vivid example: “Take, for instance, a sign outside a Catholic bookstore. If the sign says, ‘Visit the Holy Land,’ it is likely an off-premises sign because it conveys a message directing people elsewhere (unless the name of the bookstore is ‘Holy Land Books’). But if the sign instead says, ‘Buy More Books,’ it is likely a permissible on-premises sign (unless the sign also contains the address of another bookstore across town). Finally, suppose the sign says, ‘Go to Confession.’ After examining the sign’s message, an official would need to inquire whether a priest ever hears confessions at that location. If one does, the sign could convey a permissible ‘on-premises’ message. If not, the sign conveys an impermissible off-premises message. Because enforcing the sign code in any of these instances ‘requires [Austin] officials to determine whether a sign’ conveys a particular message, the sign code is content based under Reed … “The majority concedes that ‘[t]he message on the sign matters’ when applying Austin’s sign code. Ante, at 8. That concession should end the inquiry under Reed.” Justice Thomas found that the majority transforms the clear precedent of “content based regulation” into an “opaque and malleable ‘term of art’ that “turns the concept of content neutrality into a vehicle for the implementation of individual judges’ policy preferences.” He warned the acceptance of Austin’s “content-based distinction” of off-premises speech restriction “plainly lends itself to “suppress[ing] disfavored speech.” Protect The 1st and the Protect The First Foundation will remain alert to any use of today’s opinion by jurisdictions to invent novel infringements on speech. As we approach Earth Day, Protect The 1st Senior Policy Advisor and former Congressman Rick Boucher (D-VA) describes the two national treasures at risk in the plan to destroy the sacred lands of Oak Flat. One is the incomparable beauty and wildlife habitat of 2,400 acres of the Tonto National Forest. The other is the constitutional right to the free exercise of religion enjoyed by all Americans.

By all accounts, Mike Pence gave a spirited talk this week at the University of Virginia. He elicited cheers and a little protest. In these days of polarization, the peaceful appearance of a national, partisan figure on a college campus counts as a “win” for free speech.

At another university, this high-profile event might not have happened. When news broke that Pence had been invited to speak to a conservative student group, student Elisabeth Bass of The Cavalier demanded the former vice president be banned from campus as a threat to LGBTQ students. An editorial board piece for that student newspaper likened Pence’s promise to “take a stand for America’s founding” to the white supremacists who rioted in Charlottesville in 2017. The university administration held firm and rightly allowed the event to go forward. Not incidentally, their decision protected the rights of students to dissent and protest Pence as well. It is UVA’s principled stand for free speech that prompted the Foundation for Individual Rights in Education (FIRE) to give the university a “green light” rating. FIRE’s rating puts the university near the top of schools that notably respect free speech. Not every university is as firm as UVA. Administrators at other institutions often waver, allowing the silencing of speakers left, right and center.

Despite Pence’s successful appearance, institutions founded on a love of discovery and discourse are still in danger of becoming silos of censorship and shaming. What’s lost is the opportunity for all sides to learn from each other. Let’s hope more students and faculty realize the surefire way to lose a debate is to ban one. The First Amendment guarantees our free exercise of religion. The Religious Freedom Restoration Act forbids the government from “substantially burdening a person’s exercise of religion.”

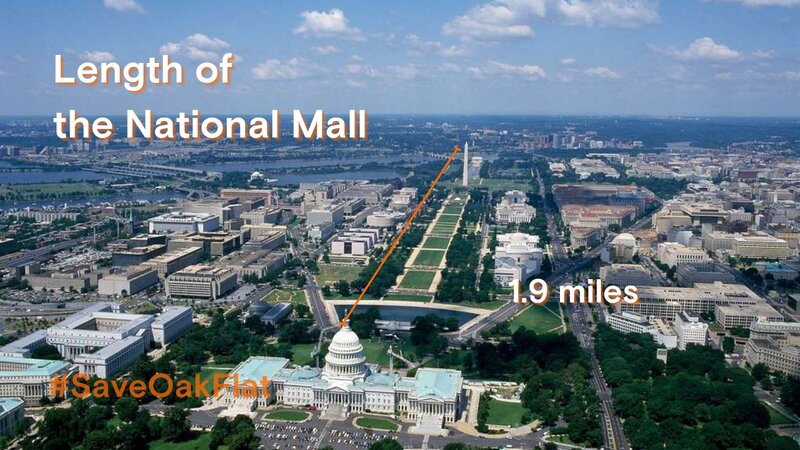

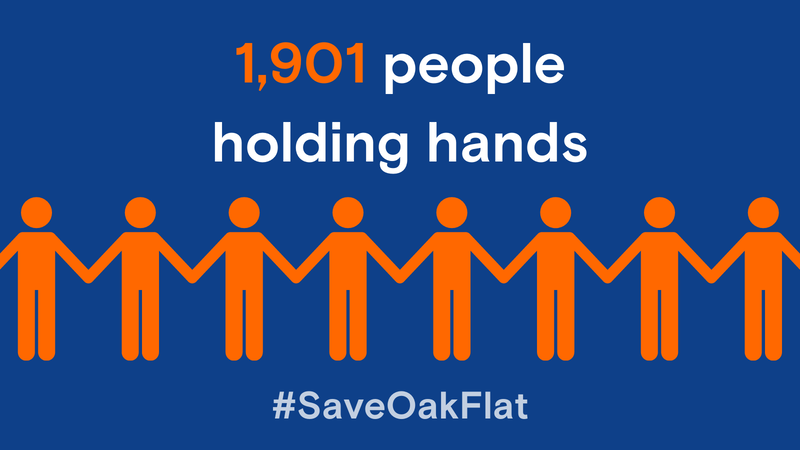

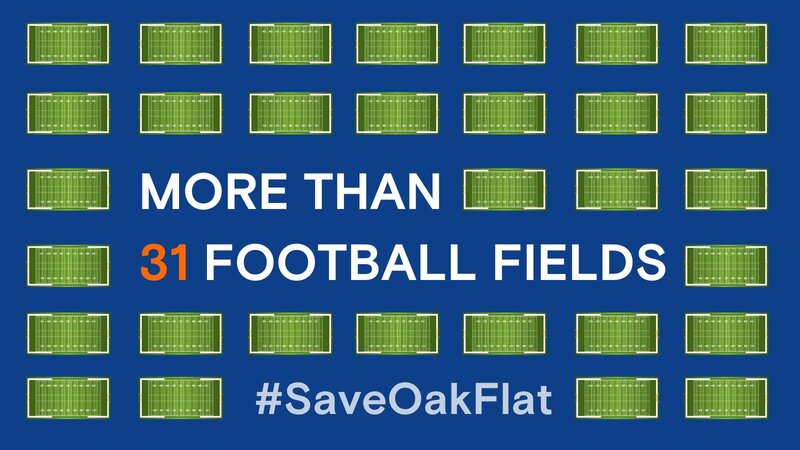

So what does a substantial burden look like? If Congress and the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals fail to protect the sacred religious lands of the Apache at Oak Flat in the Tonto National Forest in Arizona, a foreign mining company will transform this site into a crater 1.8 miles long and as deep as two Washington Monuments. Try holding a worship service, a coming-of-age ceremony, or a gathering of ceremonial and medicinal herbs at the bottom of such a hole surrounded by almost two miles of empty space. Here are some great tools for visualizing a substantial burden (hat tip to BJC). Rick Boucher: Necessary for the Protection of Civil LibertiesOn Wednesday, the House Judiciary Committee unanimously advanced the Protect Reporters from Exploitive State Spying, or PRESS Act, sponsored by Rep. Jamie Raskin (D-MD), setting it up for likely passage on the House floor.

Prior versions of this bill, introduced by Protect The 1st senior advisor, Rep. Rick Boucher (D-VA), and then-Rep. Mike Pence (R-IN), passed the House in 2007 and 2009 with more than 400 votes. It has been promoted in years past, not only by the current Committee Chair and Ranking Member, but also by now-Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer (D-NY) and Sen. Lindsey Graham (R-SC). Today’s rare and spirited agreement between committee members of both parties reflects their awareness of a serious concern. In recent years, there have been many media accounts of investigations by overweening prosecutors amounting to fishing expeditions into the notes, files, records, cellphones, laptops, and computers of reporters. Journalists from CNN to Fox News have been targeted under Democratic and Republican administrations. There have been suspicions of political motives in some of these investigations. The PRESS Act would grant journalists in legal proceedings arising under federal law a privilege to refrain from revealing confidential news sources, with reasonable exclusions. “The revelations of investigative journalists and the protection of their sources irritate the powerful,” said Rick Boucher, advisor to Protect The 1st who sponsored the bill when he served on the House Judiciary Committee. “But journalistic inquiry is absolutely necessary for citizens to hold our government accountable in the protection of our civil liberties.” Boucher called on the House to schedule a vote and for past sponsors in the Senate to take up the measure as well. |

Archives

June 2024

Categories

All

|

ABOUT |

ISSUES |

TAKE ACTION |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed