|

Over the weekend, former Secretary of Defense Mark Esper unveiled a lawsuit against the department he once led. As the law requires former U.S. officials to do, Esper submitted his memoir – A Sacred Oath – to the government for a review of any material that could damage national security. The Pentagon sent his manuscript back with redactions of words, sentences and whole paragraphs across about 60 pages. No written explanation for the redactions was offered.

A week before Esper filed suit to free his book from redaction, the American Civil Liberties Union and the Knight First Amendment Institute petitioned the U.S. Supreme Court to review this whole process of “prepublication review.” They acted on behalf of five former employees of the Office of Director of National Intelligence, the CIA, the Naval Criminal Investigative Service and the Marine Corps. Prepublication reviews, once a limited program imposed on former CIA and other intelligence-agency employees, have since widened into a vast system of lifelong prior restraint applied to millions of Americans who were once in government service. In the prepublication arena, ACLU and Knight are taking dead aim at a 41-year-old precedent, Snepp v. United States (1980). Frank Snepp was a CIA intelligence analyst in Saigon and one of the last Americans to leave after the collapse of the South Vietnamese regime. In private life, Snepp published a scathing book in 1977, Decent Interval, portraying the CIA as inept and the Nixon Administration as both self-deceiving and Machiavellian. Snepp did not clear his book with the CIA, despite having signed an employment contract committing him to do so. When the agency sued Snepp, the former analyst argued that he was being subjected to prior restraint, a violation of the First Amendment. The Court disagreed. Six Justices upheld a lower court ruling that Snepp had breached the “constructive trust” between himself and the CIA. The Court also stripped Snepp of all his royalties, about $300,000. The courts might also take note of a more recent standard, however, applied to former National Security Advisor John Bolton after he wrote a memoir, The Room Where It Happened. When officials in the Trump Administration sat on Bolton’s book, which included many anecdotes embarrassing to President Trump, Bolton published his book anyway. The Department of Justice sued for Bolton’s profits and launched a criminal investigation. In June, the current attorney general, Merrick Garland, dropped the lawsuit and investigation. General Garland is moving toward a better approach, a direction that should be picked up by the courts. Revelations and insights from former government officials give Americans a sharper understanding of the workings of our government. The current prepublication system is too broad, too clunky, and a defilement of the First Amendment. Update: Shurtleff v. Boston: DOJ Cites “Viewpoint Discrimination” in Religious Liberty Case11/29/2021

Protect the First Foundation filed an amicus brief in Shurtleff v. Boston on Nov. 22nd in support of petitioners Harold Shurtleff and Camp Constitution. On the same day, the U.S. Department of Justice filed a brief of its own in support of the petitioners.

In this case, the city government of Boston allowed groups that host events on a city plaza to hoist their flags on a city-owned flagpole. Boston’s website states that the flag-raising program commemorates “flags from many countries and communities” with a goal to “foster diversity and build and strengthen connections among Boston’s many communities.” But when Camp Constitution — a group dedicated to celebrating the nation’s Judeo-Christian heritage and the Constitution — sought to fly its flag, the city denied it permission. The U.S. Court of Appeals for the First Circuit ruled that Boston was permitted to deny the flying of Camp Constitution’s flag (which includes a crimson cross against a blue background). The 1st Circuit reasoned that the decision was permissible because the flag would have been a “powerful governmental symbol” in favor of a religion. (Many have noted the irony of Boston taking this position. Its city flag proclaims in Latin, “God be with us as he was with our fathers.”) Now the Biden Administration’s DOJ is lining up behind arguments made by Protect the First Foundation and 15 other groups that have filed amicus briefs, including the Becket Fund and the American Civil Liberties Union. The DOJ wrote that the city’s flag-flying program “is not government speech” at all. The DOJ brief noted that the Supreme Court has “emphasized that the government cannot transform private speech into government speech merely by approving private messages expressed in a forum for private speakers.” Most importantly for free speech and religious liberty, the DOJ brief argues that while some reasonable content- and speaker-based restrictions are allowed in some of these forums, viewpoint discrimination is prohibited. DOJ asserted: The Court has long held that denying access to an otherwise-available forum simply because of the religious nature of the speech is viewpoint discrimination. DOJ’s position is rooted in a Supreme Court ruling in Lamb’s Chapel v. Center Moiriches Union Free School District, 508 U.S. 384 (1993) and Rosenberger v. Rector & Visitors of University of Virginia, 515 U.S. 819 (1995). In Lamb’s Chapel, the Court upheld the right of a Christian organization to conduct a series of films and discussions “from a Christian perspective” after hours at a public school otherwise open to many other civic and community organizations. And in Rosenberger, the Court held that the University of Virginia unconstitutionally discriminated based on viewpoint when it excluded religious activities from otherwise available funding. Bottom line: The Justices of the Supreme Court should reaffirm that when government treats religious speakers less favorably than nonreligious speakers, it is engaging in impermissible viewpoint discrimination. Becket Law recently released its third Religious Freedom Index, 21 questions put to a nationally representative group of 1,000 American adults. The results portray a nation that values the contributions of religious organizations to the well-being of the United States.

The poll also shows that Americans strongly support a level playing field for faith-based organizations, wanting the government to partner with them on fair and equal terms. Becket’s Religious Freedom Index demonstrates a widespread desire to hear faith-based opinions and worldviews, important to many Americans in these disruptive times. Religious Freedom: Overall, backing for religious freedom increased in this year’s index, pushing it to a new high of 68 percent on a 0-100 scale. Level Playing Field: More Americans than ever before responded that they believe religious organizations should be just as eligible to receive government funding as non-religious organizations – a six-point increase from the previous year to a high of 71 percent. Value of Free Speech: 62 percent of respondents believe people of faith should be free to voice their religiously based opinions in public, even on controversial topics. Parents and Children: 63 percent of respondents said that parents are the primary educators of their children and should have the final say in what their children are taught. Closures: In some parts of the United States during the pandemic, there was an imbalance between how local and state governments treated many commercial and cultural activities and religious ones when it came to pandemic management and closures. In Becket’s poll, a majority said that funerals and religious services should be considered essential activities. Becket’s Religious Liberty Index demonstrates that Americans have a growing appreciation of the role of religious organizations and religious liberty. Most Americans still agree with Tocqueville’s adage: “The safeguard of morality is religion, and morality is the best security of law and the surest pledge of freedom.” The Filming of George Floyd’s Murder Would Have Been Illegal in Boston James O’Keefe and his Project Veritas brand of gotcha reporting has twice now made him the test case of the boundaries of First Amendment protection of journalists. “You might love, hate or simply want to ignore Project Veritas,” said Gene Schaerr, Protect The 1st general counsel. “But their rights are everyone’s rights.”

The recent raid on O’Keffe’s home by the FBI and the confiscation of his cellphone provoked critical comment from the American Civil Liberties Union and New York Times media columnist Ben Smith. Less noticed was the denial today by the U.S. Supreme Court of Project Veritas Action Fund v. Rollins, in which that conservative activist group sought to overturn a ruling from the U.S. Court of Appeals for the First Circuit. Unlike many other federal courts, the First Circuit ignored the threat to the First Amendment posed by a Massachusetts law that makes it illegal for anyone but law enforcement officers to record others without their permission. In our amicus brief, Protect The 1st noted a long history of the public interest being served by the exposure of misdeeds, from the undercover reporting of Nellie Bly in 1887 to 18-year-old Darnella Frazier, who received a Pulitzer Prize citation for recording the murder of George Floyd by a policeman in Minneapolis in 2020. Protect The 1st will continue to defend the standard in many parts of the country that affirms Americans’ right to record. We will continue to look for other opportunities to encourage the Court to resolve the important legal issues presented in Project Veritas’ petition. When the U.S. Supreme Court hears oral arguments in Shurtleff v. City of Boston on Jan. 18, 2022, it will examine a case in which Boston city officials allowed hundreds of groups that applied to fly a flag on a city flagpole to do so – with one exception.

Boston had designated a flagpole near City Hall Plaza to be available for private persons and groups for events. From 2005 to 2017, Boston allowed 284 flag raising events, from a gay pride flag to a Bunker Hill Flag, with no prior review of their messages. No applications were rejected. Then came Camp Constitution, a group whose mission is to “enhance understanding of the country’s Judeo-Christian heritage, the American heritage of courage and ingenuity, the genius of the United States Constitution, and free enterprise.” The group wanted to host an event celebrating the ”historical civic and social contributions of the Christian community to the City of Boston, the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, religious tolerance, the Rule of Law, and the U.S. Constitution,” by hosting an event at Boston’s City Hall Plaza that would raise “the Christian Flag,” which displays a red Latin cross. But the Boston city government refused to grant permission, claiming it had a policy of not allowing religious flags to be raised on city-owned flag poles—even though many of the flags raised previously, including Boston’s own flag, display religious words or imagery. Harold Shurtleff and other members of his Camp Constitution group sued. The U.S. Court of Appeals for the First Circuit upheld the city’s decision, holding that when private groups and individuals raised flags on City Hall Plaza, it was Boston, not those groups or individuals, that did the speaking. That meant, in the First Circuit’s eyes, that Camp Constitution’s request wasn’t protected by the First Amendment. In an amicus brief filed in support of Shurtleff and Camp Constitution, Protect the First Foundation demonstrates that: “By reducing the amount of protection speech receives as governmental regulation of that speech increases, the courts have turned the First Amendment on its head.” Protect The 1st shows that the First Circuit Court erred in defining the flagpole as “government speech.” If that ruling is correct, then the court is forcing the Boston taxpayers to endorse all the messages contained in the 284 flags that were flown. It is easy to see how obnoxious that doctrine would be in a free society: If in 2020 the White House had hoisted a flag proclaiming “Trump 2020—Keep America Great,” it would have been clear that the government was using taxpayer-funded property to express a political message. Likewise, the Commonwealth of Virginia surely could not use state funds to erect a giant billboard reading, “Virginia Says Keep Our State Blue!” Such efforts have the self-evident goal of using the compelled funding and machinery of the State to manipulate public opinion. Protect The 1st’ Foundation quoted Thomas Jefferson, who wrote that “to compel a man to furnish contributions of money for the propagation of opinions which he disbelieves and abhor[s] is sinful and tyrannical.” If the First Circuit is correct, then Boston is forcing taxpayers to pay for government speech that they may or may not agree with. In fact, as the brief asserts, the City of Boston was merely allowing private speech on a public venue. “If private speech could be passed off as government speech by simply affixing a government seal of approval, government could silence or muffle the expression of disfavored viewpoints.” And because the flag raisings are not government speech, Boston can’t choose to exclude disfavored viewpoints—including religious viewpoints. But that’s exactly what Boston did, which is why the Supreme Court should reverse the First Circuit. Oak Flat Religious Site: The Rio Tinto/BHP Plan to Dig a Crater Two Washington Monuments Deep11/17/2021

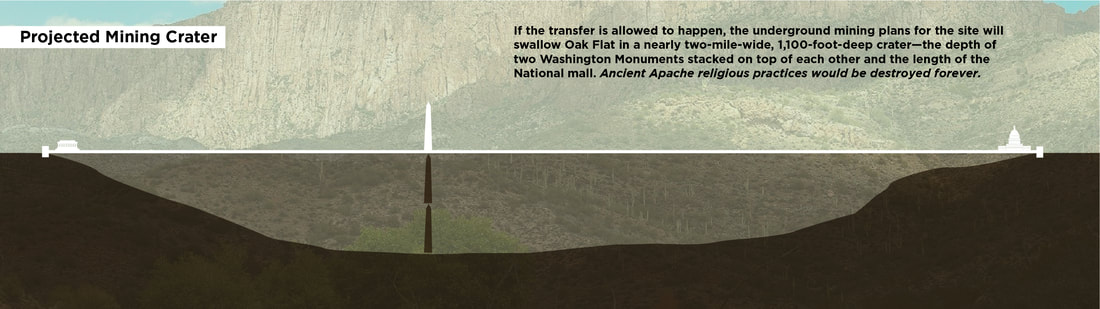

Legacy of a DesecrationProtect The 1st works with a coalition of religious liberty advocates to support the efforts of the Apache Stronghold to prevent the utter destruction of their sacred site.

This site in the Tonto National Forest, known as Oak Flat, is the sole place for the Western Apache to perform key religious ceremonies. What Mount Sinai is for the Jews and the Vatican is for Catholics, Oak Flat is for the Apache. In a last-minute, midnight Congressional deal, the Apache’s sacred land was targeted in a land swap deal to allow a foreign mining consortium – Resolution Copper, combining mining companies Rio Tinto with BHP – to obliterate that site. This would be a staggering violation of religious freedom and the Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA), the U.S. Constitution and solemn treaty agreements between the Apache and the U.S. government. As the Apache exhaust their judicial and administrative remedies, Protect The 1st provides the following graphic – courtesy of the Becket law firm – that shows exactly what this Rio Tinto-BHP project will leave in its wake. When the U.S. Supreme Court heard oral argument last Wednesday in Austin, v. Reagan National Advertising, a case asking about the city of Austin’s restriction on billboards and signage, many of the Justices’ questions echoed themes advanced in the amicus brief filed by Protect The First Foundation.

Austin city code prohibits signs from displaying messages that advertise “a business, person, activity, goods, products or services not located where the sign was installed.” A sign cannot even direct people to another location. Such “off-premise” signs are forbidden, with allowance made only for older, grandfathered signs. Protect The First Foundation’s brief explained that regulations “that turn on the content of speech are particularly troubling and prone to abuse, even where they are not overtly based on the viewpoint of the restricted speech. Often, a content restriction is merely a proxy for viewpoint discrimination.” The Supreme Court unanimously reached a similar conclusion in 2015 in Reed v. Town of Gilbert, when it held that an Arizona town could not impose different restrictions on the display of temporary signs based on the messages they conveyed. The Fifth Circuit applied this logic to the Austin law and held that any time an officer must read a sign to apply the law, the law is content based and must meet exacting strict scrutiny under the First Amendment. Justice Clarence Thomas defined the issue in culinary terms, asking if Austin’s famous Franklin BBQ could post a sign at the restaurant, but could not post such a sign somewhere else. The attorney for Austin said that was the case under the city code. Justice Thomas pointedly asked if location-based regulation of speech is also a content-based distinction: “So, in other words, I can’t say certain things unless I’m at a certain location? I can’t say ‘Eat at Franklin’s’ unless I’m at Franklin’s?” Justice Brett Kavanaugh asked whether strict scrutiny would apply if the standards were content-based. He also asked whether, if the standards are not content-based, the weaker standard of intermediate scrutiny apply. Austin’s attorney agreed strict scrutiny would be tough for a signage regulation to meet and argued for intermediate scrutiny. Kannon Shanmugam, the attorney for Reagan National, a family-owned business in Austin, saw an opening. He said: “Under this Court’s decision in Reed, Austin’s distinction between signs advertising on-premises and off-premises activities is content-based … A through line of this Court’s First Amendment cases is that whatever the standard of review, a regulatory distinction between different types of speech has to bear some relation to the governmental interest asserted.” He then put forward an example of how content cannot be separated from Austin’s regulation: “[I]f you think about it from the perspective of the owner of the premises, that owner’s speech is being limited and plainly being limited on the basis of content … Let’s say you’re a church and you want to advertise the services that take place every Sunday on your premises. Of course, under Austin’s ordinances, you can do that. “But what you can’t do is to use your digital sign to advertise an interfaith service that might be taking place at the Jewish synagogue down the road. That is a limitation on the subject matter of your speech.” The Protect The First brief took an approach that was as broad as the synagogue example was specific. The brief compared the compromising of First Amendment rights in the Austin case to the compromising of the Fourteenth Amendment’s Equal Protection and Due Process Clauses in the landmark case Loving v. Virginia, which struck down restrictions on interracial marriage. That the substance of the content restriction depends upon the non-content fact of location, and varies with every location involved, does not make it content neutral any more than the restrictions on interracial marriage struck down in Loving were race-neutral because they applied to persons of any race and varied based on the race of their prospective spouse. From the oral argument, there is a significant chance the Court will agree with Protect The First Foundation that the Austin code is subject to and fails First Amendment strict scrutiny. But even if strict scrutiny does not apply, we demonstrated the code should fail even lesser scrutiny because the city has not identified any valid, specific and genuine government interest in limiting signs to messages about their specific location. Analisa Torres, a federal judge from the Southern District of New York, made the right call late last week in ordering the Department of Justice to stop the “extraction and review” of contents from two cellphones belonging to Project Veritas founder James O’Keefe.

This order followed a raid on O’Keefe’s home and that of two of his colleagues presumably to learn the identities of “tipsters” who gave the conservative journalist access to the diary of President Biden’s daughter, Ashley Biden. The FBI launched a pre-dawn raid on O’Keefe’s home, handcuffed him and removed his electronic devices. O’Keefe told Fox News: “They confiscated my phone. They raided my apartment. On my phone were many of my reporters’ notes, a lot of my sources unrelated to this story and a lot of confidential donor information to our news organization.” O’Keefe acknowledges Project Veritas was given the diary, but insists he had no idea that the diary was stolen. He also maintains that he had turned it over to law enforcement, sought to turn it over to a lawyer for Ms. Biden, and had not published its contents. Provided that O’Keefe is telling the truth that he or his colleagues were not involved in skullduggery behind the theft of a diary, his actions were no different from that of many other journalists. ACLU, which is no admirer of O’Keefe and said a reasonable observer could question if Project Veritas’s activities are journalism, nevertheless condemned the actions of the FBI as bad precedent. ACLU’s Brian Hauss wrote: "Unless the government had good reason to believe that Project Veritas employees were directly involved in the criminal theft of the diary, it should not have subjected them to invasive searches and seizures." The same justification for rifling through physical or digital files in this case could have been made for any number of award-winning investigative works by The Washington Post and The New York Times, where anonymous sources provided access to information. Perhaps with this in mind, Times media columnist Ben Smith tweeted: “Don’t think journalists should be cheerleading this one.” Whatever one thinks of O’Keefe and his gonzo journalism from the right, the heavy-handed treatment of any journalist is a deterrent to reporting, prior restraint inimical to the First Amendment. Justices of the U.S. Supreme Court in the oral argument for Ramirez v. Collier Tuesday addressed the issue of a condemned man’s religious rights at his execution – coming from angles both critical and approving of an expansive view of those rights.

John H. Ramirez was convicted of stabbing a convenience store clerk to death when he was twenty years old. Now 37, Ramirez claims to have had a conversion experience and requests that his pastor be allowed to lay hands on him and pray while he is executed by lethal injection. Ramirez based his request on the Religious Land Use and Institutionalized Persons Act (RLUIPA), which the Court had previously found to grant inmates an “expansive protection of religious liberty.” Texas rejected his request. (In September, Protect The 1st filed a brief urging the Court to recognize that denying Ramirez’s wish would be a substantial burden on his free exercise of religion.) In Tuesday’s hearing, Justice Brett Kavanaugh’s circled around the question of whether the State of Texas has a compelling interest in ensuring that executions are carried out with “zero risk” of interference with the process. He noted that having “another person in the room” heightens risk to the execution process. Later, Justice Amy Coney Barrett asked if the State of Texas expected “zero risk” to the procedure to be the acceptable compelling interest for the state. Ramirez’s attorney, Seth Kretzer, said no such incidents of interference from clergy in Texas executions had occurred in the last 100 years. He also noted that any religious accommodation – such as gathering inmates for religious ceremonies as envisioned by RLUIPA – would necessarily entail some small degree of tolerable risk. Justice Samuel Alito expressed concern that granting Ramirez’s request could lead to “an unending stream” of variations on this case. Noting that correctional officers would prefer any contact between the prisoner and pastor be as far from the site of a lethal injection to the arm, Alito suggested the touching could be done on the foot. Would the court later have to hear cases about touching a knee, the hand or the head, Alito asked, adjudicating “the whole human anatomy?” Justice Sonia Sotomayor showed the greatest sympathy for Ramirez. She batted down the complaint of the Texas Solicitor General that Ramirez’s filings had delayed his execution, while ignoring the delays the state’s own, often tardy, denials have caused. Attorney Kretzer got the last word, telling the court that the only botched executions in recent history occurred at the hands of incompetent administrators of fatal drugs. Kretzer summed up the case for Ramirez in an eloquent statement to The Corpus Christi Caller-Times. The First Amendment applies in the most glorified halls of power and also in the hell of an execution chamber. This is the season when leaves turn orange and red. The air becomes delightfully crisp. And college administrators turn out to tell student political organizations that they cannot exercise their First Amendment right to advocate for political candidates in the upcoming election.

In this off-year election cycle, the director of student activities at Washington & Lee University told that school’s Young Republicans that they could not display campaign materials in support of Glenn Youngkin, the Republican candidate for governor. In 2016, administrators for the Georgetown University Law Center prevented a group of students supporting Sen. Bernie Sanders’ bid for the Democratic nomination for president from handing out campaign materials on campus. “The protection of political speech is at the very core of the purpose and meaning of the First Amendment,” said Bob Goodlatte, senior policy adviser to Protect The 1st and a graduate of Washington & Lee University law school. “Every college and university must have a keen recognition of this central truth of our system.” In these incidents, administrators incorrectly claim that the school’s tax-exempt status requires this limitation. And it does – for non-profit colleges and universities, and for administrators and faculty themselves when acting in their official capacities on behalf of or through their organizations. IRS Code § 501 (c) (3) requires tax-exempt organizations “not to participate in, or intervene in (including the publishing or distributing of statements), any political campaign on behalf of (or in opposition to) any candidate for public office.” But the language of the Internal Revenue Service is unequivocal regarding the rights of students to exercise political speech. For example, IRS code explicitly allows student newspapers to express political views. Even though the facilities for the newspaper are furnished by the university, the IRS recognizes that the educational mission of a university benefits from allowing student journalists to express their views on the issues and candidates of the day. Similarly, another rule allows political science courses to dispatch students to work on political campaigns as a part of their education. And there is no IRS prohibition against student political organizations from putting up booths and handing out literature for “Bernie,” “Glenn,” “Donald” or “Joe.” Washington & Lee’s own policy states: Student political organizations (College Republicans, Young Democrats, etc.) are not prohibited from pursuing their normal activities consistent with the academic nature of their endeavors. Washington & Lee requires such groups to pay the student organization rates for using institutional facilities and declare any appearance by a candidate for political office to be for “educational” purposes. And, of course, it would be a violation of the IRS code for a student group to undertake political activity at the behest of a college, its administrators or faculty. And even if at some future date the IRS code insisted that private universities suppress the independent political speech and association of its students, that would be such a severe restriction on freedom of speech that it is hard to imagine such a law or regulation surviving any level of constitutional scrutiny. “It is likely that Washington & Lee University will live up to its policies and ideals,” Goodlatte said. “The quest for political freedom on campus, however, is an ongoing struggle with students as well as administrators.” Last week, the student senate of Wichita State University denied the application of a student chapter, Turning Point USA, which advocates “principles of freedom, free markets and limited government.” The student senators voted 21-14 not to grant the club and its 165 members status as a student organization. As it turns out, however, there is a student supreme court on campus, which overturned the vote and allowed Turning Point to be recognized. That ruling cited the First Amendment and many clauses in the university’s Student Bill of Rights. (And while a state university is directly bound by the Fourteenth and First Amendments, the principle is the same regarding any supposed IRS compulsion for private universities: What government cannot do directly it cannot do as a condition of tax exempt status.) It is easy to see why some might be offended by Turning Point, whose slogan is “Socialism Sucks,” or partisans by Bernie Sanders, or by Glenn Youngkin. A 2017 poll of 1,500 undergraduates reported by the Brookings Institution shows that 51 percent of students believe they have a right to shout down controversial speakers. Nineteen percent believe that violence is justified. “Perhaps the continuing inability of students and administrators alike to respect or even understand the First Amendment may point to the deficiencies of not just higher education, but in what used to be called a civics education in high school,” Goodlatte said. Priscilla Villarreal is a citizen journalist who uses her cell phone to live-stream videos of traffic accidents and crime scenes. Known on Facebook as Lagordiloca (“the big, crazy lady”), Villarreal has managed to crawl under the skin of local law enforcement.

She live-streamed Laredo Police Department officers choking an arrestee during a traffic stop. She criticized the Webb County District Attorney for not charging a relative of one of its prosecutors, despite evidence that the relative had abused animals. When she recorded a crime scene from behind a barricade, an officer threatened to confiscate her phone – while ignoring members of the traditional media standing next to her. In April, 2017, Villarreal posted a story about a U.S. Border Patrol agent who had committed suicide. A month later, she posted the last name of a family involved in a fatal car crash. In both instances, she had confirmed her information with a Laredo Police Department officer, just as any journalist would. Six months later, Villarreal was arrested and charged with two third-degree felony counts for violating a Texas statute outlawing “Misuse of Public Information.” The affidavit in support of the arrest warrant said she had published “nonpublic” information. After turning herself in, Villarreal was followed in the booking process by police officers who mocked her and took pictures of her in handcuffs. The statute in question largely deals with public officials who use inside information for their own benefit. The “benefit” that private citizen Villarreal was charged with illicitly seeking was attracting more followers to the then-120,000 audience for Lagordiloca. By this logic, a similar “benefit” could be construed from any story that brings followers, watchers or readers to a commercial media news outlet. A district court dismissed Villarreal’s First, Fourth and Fourteenth Amendment claims for her defense and rejected her right to seek redress. On Nov. 1, Judge James Ho of the 5th Circuit of Appeals reversed this ruling. His findings should be printed and posted in every police station in the United States. If the First Amendment means anything, it surely means a citizen journalist has the right to ask a public official a question, without fear of being imprisoned. Yet that is exactly what happened here: Priscilla Villarreal was put in jail for asking a police officer a question. If that is not an obvious violation of the Constitution, it’s hard to imagine what would be. Judge Ho went on to address the district court’s next mistake, which prevented Villarreal from pursuing a wrongful arrest claim. And as the Supreme Court has repeatedly held, public officials are not entitled to qualified immunity for obvious violations of the Constitution. The district court accordingly erred in dismissing Villarreal’s First and Fourth Amendment claims on qualified immunity grounds. The district court also erred in dismissing her Fourteenth Amendment claims for failure to state a claim. This case should resonate on Capitol Hill, where Rep. Jamie Raskin and Sen. Ron Wyden have introduced the Protect Reporters from Exploitive State Spying (PRESS) Act. This bill would create a federal statutory privilege to protect journalists from being compelled to reveal confidential sources and prevent federal law enforcement from abusing subpoena power. Though the PRESS Act addresses different issues than the ones at the heart of the Villarreal case, debate about the role of the press should be informed by the need to offer wide protections to citizen journalists. While law enforcement in Laredo comes to terms with the law – and the likelihood they will be sued – they should also contemplate the law of unintended consequences. Since her arrest, Lagordiloca has added another 70,000 followers. |

Archives

June 2024

Categories

All

|

ABOUT |

ISSUES |

TAKE ACTION |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed