|

California, known for its progressive values and innovation, is increasingly becoming a battleground over the regulation of speech. The state's regulatory, political, and educational bodies are systematically encroaching on the fundamental right to free expression, attempting to manage and control speech in ways that undermine the First Amendment in the schools and among businesses.

When California sets a precedent, the implications for free speech rights across the country are profound, warranting close scrutiny and robust debate. Yet in California, recent actions reflect a shift towards control and censorship, challenging this essential liberty. Consider the legal battle involving X Corp., formerly known as Twitter. The company has been fighting against surveillance and gag orders that infringe on X’s First Amendment rights while also threatening the Fourth and Sixth Amendment rights of its users. When the government demands access to personal data stored by companies like X Corp. and then issues Non-Disclosure Orders (NDOs) to keep this secret, it coerces companies into acting as government spies, unable to speak to their users about the breaches of their privacy. This case highlights a broader pattern in California's legislative and judicial landscape. One recent law, California Bill AB 587, mandates that social media companies disclose their content moderation practices. Legal scholar Eugene Volokh has argued that this law pressures companies to engage in viewpoint discrimination, reveal their internal editorial processes, and do the government's bidding in managing speech. How would that be different from requiring newspapers to explain their editorial decisions to the government? These laws and regulations are often claimed to be justified as necessary for combating hate speech, misinformation, and harassment; however, they impose significant burdens on companies and threaten to stifle free expression. A court recently ruled against X Corp. in its attempt to block the law requiring it to disclose to the government the internal deliberations of its content moderation policies. While transparency in moderation practices might seem beneficial, the forced disclosure could lead to state-enforced censorship and coercion of private editorial processes, undermining the very principles of free speech the First Amendment is meant to protect. The state's approach to managing speech extends beyond digital platforms. In a recent disturbing case, an elementary school disciplined a first grader for drawing a benign picture with the phrase “Black Lives Matter.” Being young and probably unaware of the larger sensitivities, this elementary school child added: “any life.” The school promptly disciplined the child without telling her parents. This overreaction reflects a broader problem with educational institutions, driven by a hypersensitivity to the perceived (or mis-perceived) demands of political correctness, that end up punishing even innocent expressions of empathy and solidarity. A federal court's support for the school's actions further highlights the precarious state of free speech rights in educational settings, from elementary school up to graduate school, law school, and medical school. California's aggressive stance on speech regulation also manifests in its legal battles over the Second Amendment. A controversial state law tried to impose attorney's fees on plaintiffs challenging gun restrictions even if they win their case, but lose any small portion of their claims. This tactic aims to deter legal challenges and silence dissent, directly contravening First Amendment rights. The law’s similarity to a Texas statute targeting abortion challengers underscores a worrying trend of using financial penalties to stifle constitutional challenges. These cases collectively illustrate a dangerous trajectory in California's approach to managing speech. The state's efforts to regulate and control various forms of expression, whether online, in schools, or through legal deterrents, represent a direct assault on the First Amendment. The complexities and nuances of speech, inherently messy as they are, cannot and should not be sanitized by governmental oversight. Fortunately, the U.S. Supreme Court remains a bulwark against regulations violating the First Amendment. The Court’s decision in AFP v. Bonta, which struck down California's requirement for non-profit organizations to disclose their donors, was a significant victory for free speech. The Court recognized that such disclosure requirements pose a substantial burden on First Amendment rights, particularly by exposing donors to potential harassment and retaliation. This case reinforces the principle that anonymity in association is crucial for protecting free expression and dissent. In the recent NetChoice opinion, a majority of the Court gave a ringing endorsement of editorial freedom, even while sending the case back for a more detailed review of the laws. We remain optimistic the Supreme Court will likewise rein in California’s antagonism toward the First Amendment if, and when, it has the opportunity. The recent session of the U.S. Supreme Court will likely be remembered for two major rulings implicating fundamental separation of powers doctrine: Trump v. United States, establishing presumptive immunity from prosecution for official presidential acts; and Loper Bright Enterprises v. Raimondo, dispensing with the long-established “Chevron Two Step” granting deference to a federal agency’s interpretation of statutes. In both instances, the Court reaffirmed our constitutional system of checks and balances, including protection against encroachment on the powers and privileges of one branch of government by another.

Against the backdrop of those headline-dominating developments, the Supreme Court also took on several important First Amendment cases, with results that were constitutionally sound. Below are the highlights – and summaries – of the Court’s First Amendment jurisprudence released in recent weeks. Food and Drug Administration v. Alliance for Hippocratic Medicine In a unanimous ruling, the Supreme Court rejected a challenge to the Food and Drug Administration’s regulation of the abortion drug mifepristone. Little noticed by the media, the Court’s opinion also firmly nailed down the conscience right of physicians to abstain from participating in abortions and prescribing the drug. Writing for the Court, Justice Kavanaugh said that the Church Amendments, which prohibit the government from imposing requirements that violate the conscience rights of physicians and institutions, “allow doctors and other healthcare personnel to ‘refuse to perform or assist’ an abortion without punishment or discrimination from their employers.” From now on, any effort to restrict or violate the conscience rights of healers will go against the unanimous opinion of all nine justices of the U.S. Supreme Court. Vidal v. Elster The Supreme Court, in another unanimous decision, overturned a lower court ruling that found that the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office’s denial of an application to trademark a phrase including the name “Trump” violated the filer’s First Amendment rights. Writing for the Court, Justice Thomas wrote that “[o]ur courts have long recognized that trademarks containing names may be restricted.” But such trademark restrictions, while “content-based” must be “viewpoint neutral.” This opinion prevents commercial considerations to scissor out pieces of the national debate. While the decision rejected a novel First Amendment claim to a speech-restricting trademark, it affirms sound First Amendment principles and protects the speech of all others who would discuss and debate the virtues and vices of prominent public figures. The Court was right to refuse the endorsement of a government-granted monopoly on a phrase about a presidential candidate. NRA v. Vullo NRA v. Vullo – yet another unanimous opinion – cleared the way for the National Rifle Association to pursue a First Amendment claim against a New York insurance regulator who had twisted the arms of insurance companies and banks to blacklist the group. Maria Vullo, former superintendent of the New York State Department of Financial Services, met with Lloyd’s of London executives in 2018 to bring to their attention technical infractions that plagued the affinity insurance market in New York, unrelated to NRA business. Vullo told the executives that she would be “less interested” in pursuing these infractions “so long as Lloyd’s ceased providing insurance to gun groups.” She added that she would “focus” her enforcement actions “solely” on the syndicates with ties to the NRA, “and ignore other syndicates writing similar policies.” The Court found for the NRA, writing that, “[a]s alleged, Vullo’s communications with Lloyd’s can be reasonably understood as a threat or as an inducement. Either of those can be coercive.” The Supreme Court’s opinion vacates the Second Circuit’s ruling to the contrary and remands the case to allow the lawsuit to continue. As the Court wrote, “the critical takeaway is that the First Amendment prohibits government officials from wielding their power selectively to punish or suppress speech, directly or (as alleged here) through private intermediaries.” And we wholeheartedly agree – censorship by proxy is still government censorship. Moody v. NetChoice In one of two cases involving the nexus of government and social media, the Court seemed to punt on making a final decision on the constitutionality of laws from Florida and Texas restricting the ability of social media companies to regulate access to, and content on, their platforms. Many commentators believed the Court would resolve a split between the Fifth Circuit (upholding a Texas law restricting various forms of content moderation and imposing other obligations on social media platforms) and the Eleventh Circuit (which upheld the injunction against a Florida law regulating content and other activities by social media platforms and by other large internet services and websites). The Court’s ruling was expected to resolve the hot-button issue of whether Facebook and other major social media platforms can depost and deplatform. Instead, the Court found fault with the scope and precision of both the Fifth and the Eleventh Circuit opinions, vacating both of them and telling the lower courts to drill down on the varied details of both laws and be more precise as to the First Amendment issues posed by such different provisions. The opinion did, however, offer constructive guidance with ringing calls for stronger enforcement of First Amendment principles as they relate to the core activities of content moderation. The opinion, written by Justice Elena Kagan, declared that: “On the spectrum of dangers to free expression, there are few greater than allowing the government to change the speech of private actors in order to achieve its own conception of speech nirvana.” Murthy v. Missouri In what looked to be a major case regarding the limits of government “jawboning” to get private actors to restrict speech, the Court instead decided that Missouri, Louisiana, and five individuals whose views were targeted by the government for expressing misinformation could not demonstrate a sufficient connection between the government’s action and their ultimate deplatforming by private actors. Accordingly, the Court’s reasoning in this 6-3 decision is that the two states and five individuals lacked Article III standing to bring this suit. A case that could have defined the limits of government involvement in speech for the central media of our time was thus deflected on procedural grounds. Justice Samuel Alito, in a fiery dissent signed by Justices Clarence Thomas and Neil Gorsuch, criticized the punt, calling Murthy v. Missouri “one of the most important free speech cases to reach this Court in years.” Fortunately, NRA v. Vullo, discussed above, sets a solid baseline against government efforts to pressure private actors to do the government’s dirty work in suppressing speech the government does not like. Later cases will, we hope, expand upon that base. Secret communications from the government to the platforms to take down one post or another is inherently suspect under the Constitution and likely to lead us to a very un-American place. Let us hope that the Court selects a case in which it accepts the standing of the plaintiffs in order to give the government, and our society, a rule to live by. Gonzalez v. Trevino Protect The 1st has reported on the case of Sylvia Gonzalez, a former Castle Hills, Texas, council member who was arrested for allegedly tampering with government records back in 2019. In fact, she merely misplaced them, and was subsequently arrested, handcuffed, and detained in what was likely a retaliatory arrest for criticizing the city manager. In turn, Gonzalez brought suit. Gonzalez’s complaint noted that she was the only person charged in the past 10 years under the state’s government records law for temporarily misplacing government documents. In 2019’s Nieves v. Bartlett, the Supreme Court found that a plaintiff can generally bring a federal civil rights claim alleging retaliation if they can show that police did not have probable cause. The Court also allowed suit by plaintiffs claiming retaliatory arrests if they could show that others who engaged in the same supposedly illegal conduct, but who did not engage in protected but disfavored speech, were not arrested. The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit threw out Gonzalez’s case, finding that she would have had to offer examples of those who had mishandled a government petition in the same way that she had but – unlike her – were not arrested. The Supreme Court, by contrast, found that, “[a]lthough the Nieves exception is slim, the demand for virtually identical and identifiable comparators goes too far.” The Court thus made it a bit easier for the victims of First Amendment retaliation to sue government officials who would punish people for disfavored speech. The controversy will now go back to the Fifth Circuit for reconsideration. *** While the Court avoided some potentially landmark decisions on procedural grounds, and offered a mixed bag of decisions concerning plaintiffs’ ability to obtain redress against potential First Amendment violations, the majority consistently showed a strong desire to protect First Amendment principles – shielding people and private organizations from government-compelled speech. Who qualifies as a journalist? Do you have to work for a mainstream media outlet? If you don’t have the imprimatur of an award-winning newspaper like The New York Times or Washington Post, does that negate your right to gather and convey information?

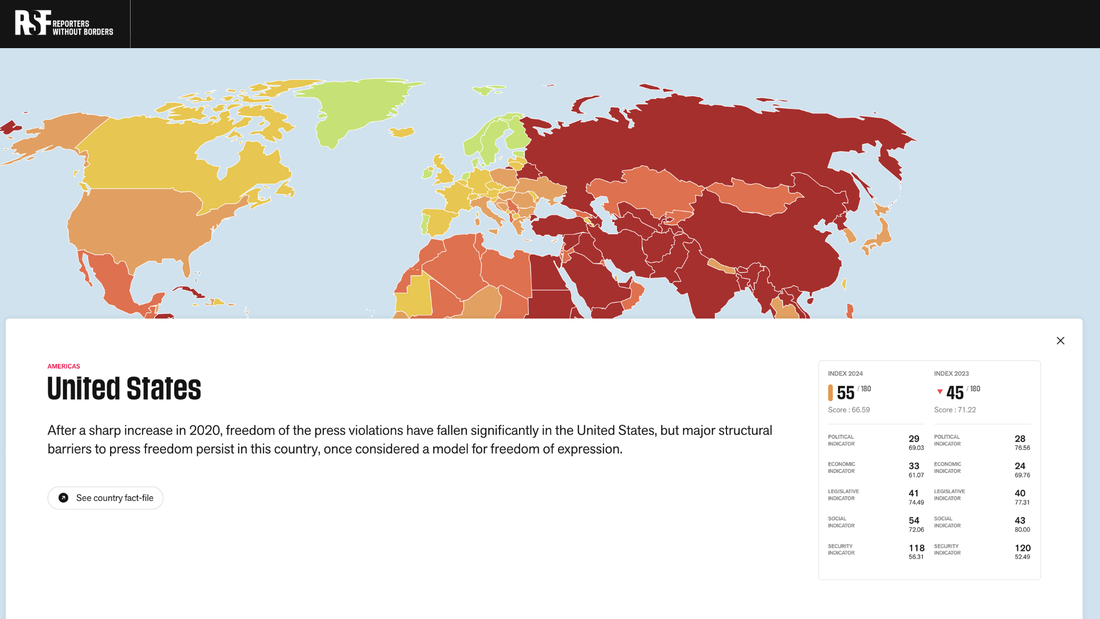

That seems to be the case in certain parts of Texas, where police have twice recently arrested private citizens for committing the crime of journalism. In 2021, the Fort Bend County Sheriff’s Office arrested and strip-searched Justin Pulliam – who posts on the YouTube channel Corruption Report – for filming police during a mental health call. Despite following police instructions to stand away from the interaction, Pulliam was charged with “Interference with Public Duties,” a Class B misdemeanor under Texas state law. It wasn’t the first time Pulliam had been legally harassed – earlier that year he was ejected from a press conference because authorities said he did not qualify as a journalist. A similar situation happened back in 2017, when Laredo police arrested citizen journalist Priscilla Villareal under a statute prohibiting the solicitation of nonpublic information where there is “intent to obtain a benefit.” AKA journalism. The Fifth Circuit initially sided with Villareal, with Judge Ho writing: “If the First Amendment means anything, it surely means a citizen journalist has the right to ask a public official a question, without fear of being imprisoned. Yet that is exactly what happened here: Priscilla Villarreal was put in jail for asking a police officer a question. If that is not an obvious violation of the Constitution, it’s hard to imagine what would be.” Unfortunately, the full court backtracked during an en banc appeal, finding that city officials had qualified immunity. As we wrote at the time, that ruling set a terrible precedent for freedom of the press – sending a message that reporters should be wary of arrest and reprisal for daring to ask questions of government officials. Now, Pulliam’s case is up before the Fifth Circuit too, following a Texas district court’s rejection of the defendants’ qualified immunity argument. We’ll see whether the judges get it right this time and acknowledge that Corruption Report constitutes a “legitimate” media outlet. In Villareal’s case, Judge Edith Jones suggested that her Lagordiloca page was not. We respectfully disagree. Courts should not be in the business of determining who is and who is not a “legitimate” reporter according to platform or reporting style. The changing technological landscape has enfranchised a new class of citizen journalists no less deserving of respect and the protections of the First Amendment than their more well-heeled counterparts. Offering a step in the right direction, the Protect Reporters from Exploitive State Spying (PRESS) Act, introduced by Sen. Ron Wyden and Rep. Jamie Raskin, brings all sorts of journalists into the fold and provides a shield for reporters’ notes and sources from prying prosecutors. The PRESS Act defines a covered journalist as someone who “gathers, prepares, collects, photographs, records, writes, edits, reports, or publishes news or information that concerns news events or other matters of public interest for dissemination to the public.” That would certainly include Pulliam and Villareal. The House passed the PRESS Act by unanimous voice vote earlier this year. The Senate should follow up and send it to the president’s desk for signature. As for the Fifth Circuit, the Pulliam case is a great chance to revise its stance and catch up with the evolution of the fourth estate. Reporters Without Borders dropped the United States 10 places on its annual rankings from last year, from 45th to 55th place out of 180 countries in its 2024 World Press Freedom Index. This is part of a trend. This NGO has downgraded the United States, which enshrines freedom of the press in our Constitution, from 17th best for press freedom in 2002 to that 55th place now.

To be fair, some of the organization’s metrics are questionable. For example, Argentina fell from 40th place last year to 66th place in 2024 after newly elected President Javier Miliei shuttered news outlet Télam and put its 700 journalists on the street. It should be noted, however, that Télam was a money-losing, state-funded news agency founded by Juan Perón and known for being a government and Peronista mouthpiece under previous administrations. So how fairly did Reporters Without Borders treat the United States? It seems overkill to us to rank the United States below the Ivory Coast, where reporters are routinely called in by prosecutors and newspapers are suspended – or Romania, where a prominent journalist who investigated the government had her personal images hacked and uploaded to an adult website. At the same time, while we can take issue with the overall ranking of the United States, this NGO is correct on what the British call the direction of travel. Protect The 1st has reported what Reporters Without Borders states: “In several high-profile instances, local law enforcement has carried out chilling actions, including raiding newsrooms and arresting journalists.” We would add to that the lack of a federal press shield law also leaves reporters vulnerable to being wiretapped and worse. The good news is that protections for reporters have a strong basis of public support in the United States. A recent survey by the Pew Research Center reveals robust support among Americans for the principle of press freedom, underscoring its vital role in our democracy. It’s heartening to note that nearly three-quarters of U.S. adults (73 percent) consider the freedom of the press — enshrined in the First Amendment — extremely or very important to the well-being of society. Still, we have reason for caution. While a significant majority of Americans acknowledge the importance of a free press, many are concerned about threats to journalistic freedom. Notably, a substantial portion of the population believes U.S. media is influenced by corporate and political interests — 84 percent and 83 percent respectively. In our polarized society, partisan differences color these perceptions of press freedom. Republicans and Independents consistently express greater concern over media restrictions and the influence of political interests compared to Democrats. Equally concerning is the broader debate over the balance between safeguarding press freedom and curbing “misinformation.” Approximately half of the American population is torn between the necessity to prevent the spread of false information and the imperative to protect press freedoms, even if it means some false information might circulate. While it's encouraging to see strong support for journalistic freedoms among Americans, local authorities must understand that raids and legal threats against reporters is intolerable under our Constitution and under the press shield laws of 49 states. And we need a federal press shield law – the PRESS Act, which recently passed the U.S. House – to reduce the shadow the Department of Justice can cast over the free exercise of journalism. We’ve got work to do. Congress Should Celebrate It by Passing the PRESS ActLike many declarations of the United Nations, the 31st anniversary of World Press Freedom Day is more aspirational than reality in many UN member countries.

In some countries, journalists are routinely killed for reporting on corrupt politicians and police agencies. UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres’ says that violence is also common among journalists covering local environmental issues like illegal mining, logging, poaching and other acts of “environmental vandalism.” Much of the repression comes from sophisticated state actors. In China, imprisoned Hong Kong publisher Jimmy Lai stayed in that jurisdiction to bravely stare down official repression after his newspaper, Apple Daily, was shuttered. In Russia, Evan Gershkovich of The Wall Street Journal remains held on specious charges of spying for the CIA by Vladimir Putin’s judicial puppets. “Journalism should not be a crime anywhere on the earth,” President Biden declared today. We agree and would only add, for unfortunately necessary emphasis, “including the United States.” While 49 U.S. states have press shield laws, there is no federal law that protects the notes and sources of a journalist from being seized by a federal prosecutor. Many U.S. reporters have gone to jail rather than bow to a prosecutor’s demand to reveal his or her sources. All the more reason to celebrate World Press Freedom in America by asking Congress to get behind the PRESS Act, which would extend these basic protections to the federal government. “If you cannot offer a source a promise of confidentiality as a journalist, your toolbox is empty,” celebrated investigative journalist Catherine Herridge told members of a House Judiciary subcommittee. “No whistleblower is coming forward, no government official with evidence of misconduct or corruption. And what that means is that it interrupts the free flow of information to the public … Journalism is about an informed electorate, which is the bedrock of our democracy.” We urge Congress to honor the First Amendment and the freedom of the press by passing the PRESS Act. Can a protest organizer be held civilly liable for the unlawful actions of another at a demonstration? That’s the question at issue in McKesson v. Doe, one with significant implications for protected speech.

The case’s circuitous journey through the courts started in 2016, when an anonymous Louisiana law enforcement officer was struck with a “rock-like” object hurled by an unknown person at a Black Lives Matter protest. This was a despicable act of violence that was in no sense expressive speech. Those who commit such acts of violence must be prosecuted to the fullest extent of the law. But what is the liability of those who organize a peaceful protest that is infiltrated by the violent? Plaintiff John Doe brought suit against activist DeRay McKesson, who organized the event, on the theory that McKesson’s role as the event organizer encompassed a duty to protect everyone present. In 2020, the U.S. Supreme Court vacated the Fifth Circuit’s decision against McKesson, which upheld a novel theory from Doe of “negligent protest.” The Court remanded the case to the Louisiana Supreme Court, instructing it to analyze whether state law actually provides for negligence liability in such situations. This decision seems to ignore precedent in NAACP v. Claiborne Hardware, which held that “[c]ivil liability may not be imposed merely because an individual belonged to a group, some members of which committed acts of violence.” The Louisiana Supreme Court ultimately reached the conclusion that state tort law does, in fact, provide Doe with a cause of action. As a result, the Fifth Circuit reinstated its ruling and the case returned again to the highest court in the land. Notably, the Supreme Court ruled in the intervening years in Counterman v. Colorado that a subjective, mens rea standard (meaning specific intent, not just negligence) is required for a finding of liability in lawsuits that seek to punish speech. Justice Kagan wrote that the “First Amendment precludes punishment, whether civil or criminal, unless the speaker’s words were ‘intended’ (not just likely) to produce imminent disorder.” Accordingly, in an order rejecting certiorari in the McKesson case earlier this month, Justice Sotomayor strongly implied that the Court has already settled this question of law. She wrote, “Although the Fifth Circuit did not have the benefit of this Court’s recent decision in Counterman when it issued its opinion, the lower courts now do. I expect them to give full and fair consideration to arguments regarding Counterman’s impact in any future proceedings in this case.” The Supreme Court clearly wants to allow some deference to state law. However, it seems entirely reasonable to require a showing of intent in situations involving the random outbreak of violence at protests. Failure to do so could have a significant, chilling effect on political speech. If civil liability can be assigned for merely organizing an event, then we’re likely to see a lot less civil discourse in the future. Journalists have similar concerns. As the Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press explains, protecting against liability for the “uncoordinated,” lawless actions of others “is a critical safeguard for reporters who attend tumultuous events where violence may break out — political rallies, say, or mass demonstrations — in order to bring the public the news.” It remains possible the Fifth Circuit may reevaluate its ruing in light of Counterman, but it’s disappointing that the Supreme Court declined to weigh-in in a meaningful way. When states start imposing low liability thresholds on protestors, it jeopardizes First Amendment protections for all of us. A House hearing on the protection of journalistic sources veered into startling territory last week.

As expected, celebrated investigative journalist Catherine Herridge spoke movingly about her facing potential fines of up to $800 a day and a possible lengthy jail sentence as she faces a contempt charge for refusing to reveal a source in court. Herridge said one of her children asked, “if I would go to jail, if we would lose our house, and if we would lose our family savings to protect my reporting source.” Herridge later said that CBS News’ seizure of her journalistic notes after laying her off felt like a form of “journalistic rape.” Witnesses and most members of the House Judiciary subcommittee on the Constitution and Limited Government agreed that the Senate needs to act on the recent passage of the bipartisan Protect Reporters from Exploitative State Spying (PRESS) Act. This bill would prevent federal prosecutors from forcing journalists to burn their sources, as well to bar officials from surveilling phone and email providers to find out who is talking to journalists. Sharyl Attkisson, like Herridge a former CBS News investigative reporter, brought a dose of reality to the proceeding, noting that passing the PRESS Act is just the start of what is needed to protect a free press. “Our intelligence agencies have been working hand in hand with the telecommunications firms for decades, with billions of dollars in dark contracts and secretive arrangements,” Attkisson said. “They don’t need to ask the telecommunications firms for permission to access journalists’ records, or those of Congress or regular citizens.” Attkisson recounted that 11 years ago CBS News officially announced that Attkisson’s work computer had been targeted by an unauthorized intrusion. “Subsequent forensics unearthed government-controlled IP addresses used in the intrusions, and proved that not only did the guilty parties monitor my work in real time, they also accessed my Fast and Furious files, got into the larger CBS system, planted classified documents deep in my operating system, and were able to listen in on conversations by activating Skype audio,” Attkisson said. If true, why would the federal government plant classified documents in the operating system of a news organization unless it planned to frame journalists for a crime? Attkisson went to court, but a journalist – or any citizen – has a high hill to climb to pursue an action against the federal government. Attkisson spoke of the many challenges in pursuing a lawsuit against the Department of Justice. “I’ve learned that wrongdoers in the federal government have their own shield laws that protect them from accountability,” Attkisson said. “Government officials have broad immunity from lawsuits like mine under a law that I don’t believe was intended to protect criminal acts and wrongdoing but has been twisted into that very purpose. “The forensic proof and admission of the government’s involvement isn’t enough,” she said. “The courts require the person who was spied on to somehow produce all the evidence of who did what – prior to getting discovery. But discovery is needed to get more evidence. It’s a vicious loop that ensures many plaintiffs can’t progress their case even with solid proof of the offense.” Worse, Attkisson testified that a journalist “who was spied on has to get permission from the government agencies involved in order to question the guilty agents or those with information, or to access documents. It’s like telling an assault victim that he has to somehow get the attacker’s permission in order to obtain evidence. Obviously, the attacker simply says no. So does the government.” This hearing demonstrated how important Fourth Amendment protections against unreasonable searches and seizures are to the First Amendment’s guarantee of freedom of the press. If Attkisson’s claims are true, the government explicitly violated a number of laws, not the least of which is mishandling classified documents and various cybercrimes. And it relies on specious immunities and privileges to avoid any accountability for its apparent crimes. Two proposed laws are a good way to start reining in such government misconduct. The first is the PRESS Act, which would protect journalists from being pressured by prosecutors in federal court to reveal their sources. The second proposed law is the Fourth Amendment Is Not For Sale Act, which passed the House this week. This bill would require the government to get a warrant before it can inspect our personal, digital information sold by data brokers. And, of course, these and other laws limiting government misconduct need genuine remedies and consequences for misconduct, not the mirage of remedies enfeebled by improper immunities. The growth of the surveillance state in Washington, D.C., is coinciding with a renewed determination by federal agencies to expose journalists’ notes and sources. Recent events show how our Fourth Amendment right against unreasonable searches and seizures and our First Amendment right of a free press are inextricable and mutually reinforcing – that if you degrade one of these rights, you threaten both of them.

In May, we reported that the FBI raided the home of journalist Tim Burke, seizing his computer, hard drives, and cellphone, after he reported on embarrassing outtakes of a Fox News interview. It turns out these outtakes had already been posted online. Warrants were obtained, but on what credible allegation of probable cause? Or consider CBS News senior correspondent Catherine Herridge who was laid off, then days later ordered by a federal judge to reveal the identity of a confidential source she used for a series of 2017 stories published while she worked at Fox News. Shortly afterwards, Herridge was held in contempt for refusing to divulge that source. This raises the question that when CBS had earlier terminated Herridge and seized her files, would network executives have been willing to put their freedom on the line as Herridge has done? In response to public outcry, CBS relented and handed Herridge’s notes back to her. But local journalists cannot count on generating the national attention and sympathy that a celebrity journalist can. Now add to this vulnerability the reality that every American who is online – whether a national correspondent or a college student – has his or her sensitive and personal information sold to more than a dozen federal agencies by data brokers, a $250 billion industry that markets our data in the shadows. The sellers of our privacy compile nearly limitless data dossiers that “reveal the most intimate details of our lives, our movements, habits, associations, health conditions, and ideologies.” Data brokers have established a sophisticated system to aggregate data from nearly every platform and device that records personal information to develop detailed profiles on individuals. To fill in the blanks, they also sweep up information from public records. So if you have a smartphone, apps, or search online, your life is already an open book to the government. In this way, state and federal intelligence and law enforcement agencies can use the data broker loophole to obtain information about Americans that they would otherwise need a warrant, court order, or subpoena to obtain. Now imagine what might happen as these two trends converge – a government hungry to expose journalists’ sources, but one that also has access to a journalist’s location history, as well as everyone they have called, texted, and emailed. It is hardly paranoid, then, to worry that when a prosecutor tries to compel a journalist to give up a source through legal means, purchased data may have already given the government a road map on what to seek. The combined threat to privacy from pervasive surveillance and prosecutors seeking journalists’ notes is serious and growing. This is why Protect The 1st supports legislation to protect journalistic privacy and close the data broker loophole. The Protect Reporters from Exploitive State Spying, or PRESS Act would grant a privilege to protect confidential news sources in federal legal proceedings, while offering reasonable exceptions for extreme situations. Such “shield laws” have been put into place in 49 states. The PRESS Act, which passed the House in January with unanimous, bipartisan support, would bring the federal government in line with the states. Likewise, the Fourth Amendment Is Not For Sale Act would close the data broker loophole and require the government to obtain a warrant before it can seize our personal information, as required by the Fourth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution. The House Judiciary Committee voted to advance the Fourth Amendment Is Not For Sale Act out of committee with strong bipartisan support in July. The Judiciary Committee also reported out a strong data broker loophole closure as part of the Protect Liberty Act in December. Now, it’s up to Congress to include these protection and reform measures in the reauthorization of Section 702. Protect The 1st urges lawmakers to pass measures to protect privacy and a free press. They will rise or fall together. Reporters treat promises of confidentiality to potential sources as sacred for a reason. The promise of anonymity is the bedrock upon which investigative journalism rests. This promise is so central to a free press that a bill to codify its protection is currently wending its way through Congress. The PRESS Act would protect journalists and their sources by granting a privilege to shield confidential news sources in federal legal proceedings.

CBS went one step further after it terminated investigative journalist Catherine Herridge: the news division reportedly seized her files, including private information about privileged sources. Lawyer Jonathan Turley writes CBS is “moving toward a resolution,” with some reports indicating CBS has already returned the files. But the initial action, which sparked widespread concern among CBS employees, is instructive about the need to protect reporters and sources. Turley in The Hill wrote that the “the timing of Herridge’s termination immediately raised suspicions in Washington. She was pursuing stories that were unwelcomed by the Biden White House and many Democratic powerhouses,” which landed her in hot water with CBS executives. After she was terminated, the network seized her notes and files, informing her that it would decide what would be released to her. Such an action defied established media tradition. “Journalists are generally allowed to leave with their files,” Turley writes. “Under the standard contract, including the one at CBS, journalists agree that they will make files available to the network if needed in future litigation. That presupposes that they will retain control of their files.” CBS also suggested that it would allow unnamed individuals to look through Herridge’s files to determine what she would have been allowed to keep. A former CBS manager said that he had “never heard of anything like this.” The Screen Actors Guild-American Federation of Television and Radio Artists union (SAG-AFTRA) has raised the issue with CBS, noting the effect of this action could have on journalistic practices and source confidentiality. If this issue is, in fact, not resolved as reported, the union could well take this to court to test Herridge’s claim to her notes. Why did CBS News risk tarnishing its own legacy? It shouldn’t matter if Herridge’s investigation is of Hunter Biden’s laptop, Donald Trump, Robert F. Kennedy Jr., or the My Pillow Guy. By originally suggesting that CBS will unilaterally decide the fate of Herridge's files, including those originating from her tenure at Fox News, the network risked undermining the willingness of sources to come forward with sensitive information for all news gatherers. This is one more reason why Protect The 1st stands firmly in favor of The PRESS Act. As we wrote last November, ironically about Catherine Herridge in a different context, the PRESS Act would have made a difference when she was ordered by a federal judge to reveal the identity of confidential sources she used for a series of 2017 stories published while she worked at Fox News. If CBS did hold on to the files, it could easily lose control of them through a leak or litigation. If ordered by a court to reveal these documents, would executives have risked jail time like Herridge has done? Although the First Amendment does not apply to a private company, CBS News should not be less supportive of a free press than the government. The accidental release by the Los Angeles Police Department of thousands of officers’ photo headshots – including, inadvertently, those of police working undercover – has resulted in a spiderwebbing series of hostile legal actions drawing in the LAPD, an angry police union, an even angrier group of undercover officers, press advocates, City Attorney Heidi Feldstein Soto, and Mayor Karen Bass. Finger pointing abounds. Yet, the party arguably at the center of the controversy is Knock LA journalist Ben Camacho, now being sued by the city to recover the costs of its own clerical error.

Camacho received the photos in 2022 pursuant to a California Public Records Act request. While the LAPD initially fought back against providing headshots of active-duty officers, they eventually capitulated following a settlement agreement in which they assented to providing all available photos except for those of officers serving in an undercover capacity. Except, they provided those, too. Soon after, at least two groups of police officers sued the LAPD. And in April, the LAPD filed suit against Camacho to prevent publication of the more than 9,300 images. That’s where press advocates came into the picture. As the Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press pointed out in its amicus brief, “the Supreme Court of the United States has long recognized prior restraints as the ‘most serious and the least tolerable infringement on First Amendment rights’ because they are ‘an immediate and irreversible sanction’ not only ‘chill[ing]’ speech but also ‘freez[ing]’ it, at least for a time. This constitutional harm is magnified when the government seeks the removal of already published information.” Indeed, the Court has on multiple occasions made it clear that when the government releases information, even if accidentally, it can’t then attempt to gag the press to prevent publication. That established legal reasoning apparently didn’t sway the Los Angeles Superior Court, which ruled for the City of Los Angeles. Camacho has since appealed. Another twist in this saga occurred more recently when the city sued Camacho for indemnification. As Freedom of the Press Foundation advocacy director Seth Stern said, the “city has hit the trifecta of anti-press First Amendment violations: first, demanding journalists give back documents the government released, second, censoring journalists from publishing information, and now, holding journalists financially liable for truthful publications ...” State intimidation of the press is nothing new, but it seems to be taking on a troubling new tenor. At Protect The 1st, we’ve documented a series of recent efforts by power-drunk officials to punish reporters for committing acts of journalism. In Alabama, a small town publisher and reporter were arrested for reporting on a grand jury leak about the alleged mishandling of COVID relief funds. In Kansas, police raided the Marion County Record in an effort to track down an informant who revealed information about a local restauranteur’s DUI. In that instance, the paper’s 98-year-old co-owner died a day after her home was raided. The LAPD debacle is further evidence of declining respect for the First Amendment and a free press. The City of Los Angeles should cease its legal gesticulating, own up to its mistake, and move on. Honest reporters should not pay for government slip-ups. The Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals just dealt a serious blow to the freedom of the press, endorsing immunity for arresting a reporter for simply asking questions of the government and publishing the answers. The case, Villarreal v. City of Laredo Texas, arose when Facebook vlogger-journalist Priscilla Villarreal, who goes by the self-deprecating nickname Lagordiloca (“crazy, fat woman”) was detained for her coverage of a traffic accident and the suicide of a U.S. Border Patrol employee in Laredo.

Villarreal swore that she corroborated the names of the deceased individuals in the suicide and traffic accident with a source in the Laredo Police Department – taking this step after independently verifying these identities. In response to her reporting, Villarreal was detained and charged with violating a Texas law that makes it a crime to solicit nonpublic information from a public servant “with intent to obtain a benefit.” During the booking process, officers surrounded Villarreal, mocked her, and took cellphone photos of her while she was being fingerprinted. The case had already appeared before the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals in 2022, when a panel of judges originally sided with Villarreal. Judge Ho, writing for the court, held that “if the First Amendment means anything, it surely means that a citizen journalist has the right to ask a public official a question, without fear of being imprisoned.” The en banc appeal, which was decided recently, held that city officials were entitled to qualified immunity and that “Villarreal sought to capitalize on others’ tragedies to propel her reputation and career.” Such weaponized language could easily be leveled against any news outlet in the country. This case sets a bad precedent for the freedom of the press if reporters can’t ask government officials questions without fear of arrest and other reprisals, with the police inflicting such injury held immune for any consequences. Consider one case in November, when reporter Hank Sanders was cited for persistently asking Calumet City officials for a comment about flooding in the town. The citation was ultimately dropped after city officials realized that enforcing the citation would prove to be more of a hassle than simply responding to Sanders and his questions. Or consider the rural Kansas police department that ransacked the offices of the Marion County Record in execution of a search warrant to track down an informant. The leaked information? A local restauranteur’s DUI record that the newspaper had already decided not to print. Computers were seized, cell phones were snatched, all just to bully the press. We have long counted on a judicial buffer to correct local abuses. Thanks to the Fifth Circuit’s expansive view of qualified immunity, and seemingly narrow view of First Amendment rights, that buffer just became thinner. If the same standard that the Fifth Circuit endorsed were to be adopted across the country, journalists would be left with little recourse when law enforcement comes crashing through their doors, but ultimately declines to prosecute them. In his dissent in the Villarreal case, Judge James Graves wrote that the Fifth’s opinion means journalists “will only be able to report information the government chooses to share” lest they face arrest and other harassment. Villarreal has already declared her intent to appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court. Protect The 1st supports Villarreal’s appeal and looks forward to her vindication for the sake of all American journalists. “Once again, the House has passed the Protect Reporters from Exploitive State Spying (PRESS) Act with unanimous, bipartisan support. Forty-nine states have press shield laws protecting journalists and their sources from the prying eyes of prosecutors. The federal government does not. From Fox News to The New York Times, government has surveilled journalists in order to catch their sources. Journalists have been held in contempt and even jailed for bravely safeguarding the trust of their sources.

“The PRESS Act corrects this by granting a privilege to protect confidential news sources in federal legal proceedings, while offering reasonable exceptions for extreme situations. Such laws work well for the states and would safeguard Americans’ right to evaluate claims of secret wrongdoing for themselves. “Great credit goes to Rep. Kevin Kiley and Rep. Jamie Raskin for lining up bipartisan support for this reaffirmation of the First Amendment. As in 2022, the last time the House passed this act, the duty now shifts to the U.S. Senate to respond to this display of unanimous, bipartisan support. I am optimistic. At a time of gridlock, enacting this bill into law would be a positive message that would reflect well on every Senator.” The Freedom of the Press Foundation reports a disturbing trend at the county and municipal levels: governments pulling official notices from local papers in retaliation for unfavorable reporting.

In Delaware County, New York, the board of supervisors dropped local newspaper The Reporter as the official county paper for printing local laws and notices in 2022, citing increased prices for advertising. A year later, however, the board wrote a letter to The Reporter’s publishers to complain about its coverage, specifically stating the true reason for the county’s decision: displeasure over certain elements of the paper’s reporting. The New York Times picked up the story. Days later, the Delaware County Attorney issued a gag order on all county employees prohibiting them from speaking to The Reporter at all. Now, the paper is suing, alleging First and Fourteenth Amendment violations. In addition to police raids of newsrooms and arrests of journalists by local governments, the defunding movement is gaining steam against already financially stressed local newspapers across the country. In Putnam County, New York, the local government terminated The Putnam County News and Recorder’s contract to publish county legal notices following supposedly critical coverage of the newly elected county executive. As in Delaware County, it seemed a blatant attempt to use the power of the purse strings to manipulate local media. Similarly, in Kansas, the attorney general issued an advisory opinion suggesting that local governments could exempt themselves from a state law requiring official notices to be published in a designated newspaper. Since then, the cities of Hillsboro and Westmoreland have done exactly that, creating heightened concerns about a lack of government transparency in the process. In Ohio, the state passed a little noticed new law in its 6,000-page budget permitting cities and towns to publish notices on their official websites rather than in local papers. (A similar action also took place in Florida.) There are benign explanations for this move. But these new standards give local governments new ammunition to employ against newspapers in an effort to control the narrative. It’s a storied tradition for municipalities to post public notices in newspapers (in fact, most cities and towns have laws requiring them to do so). The purpose is to keep residents and voters informed of official government actions – local meetings, land sales, zoning changes, and the like. And while failing to uphold this practice does not violate the Constitution, government retaliation against newspapers based on their reporting certainly does. Gagging county employees willing to speak on matters of public concern, moreover, violates both the newspapers’ First Amendment rights and those of the prospective speakers and whistle-blowers. We applaud the Freedom of the Press Foundation’s efforts to support local papers and fight back against officials more concerned with consolidating power than protecting speech. “The First Amendment guarantees the public a qualified right of access to judicial proceedings and documents that is rooted in the understanding that public oversight of the judicial system is essential to the proper functioning of that system and, more generally, to our democratic system of self-governance.”

A hearing last week before the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals includes this quote from an amici brief by the Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press and 38 other media organizations including the Associated Press, Atlantic Monthly Group, Axios, McClatchy, the National Press Club, the New York Times and The Washington Post. At issue is Virginia’s Officer of the Court Remote Access (with the charming acronym of OCRA) system, which allows attorneys and certain government agencies online access to non-confidential civil court records from participating circuit courts in the state (105 courts out of 120 in the Commonwealth). Those not allowed online access to court records through OCRA include, well, everyone else – but most notably members of the press, who are forced to travel to each circuit court individually, in person, during weekday business hours in order to obtain documents and properly report on proceedings of public concern. Virginia’s practice stands in contrast with the policies of at least 38 other states that allow unfettered online access to court records for all members of the public. Accordingly, one media outlet, Courthouse News Service, filed a complaint in the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia against a Virginia court clerk and the administrator of OCRA, alleging that the “Non-Attorney Access Restriction” constitutes an unconstitutional speaker-based restriction on speech. Although the district court initially rejected the defendants’ motion to dismiss, it ultimately granted summary judgment, finding that the attorneys-only rule was a content-neutral time, place, and manner restriction and thus did not require a strict scrutiny analysis. Courthouse News subsequently appealed to the Fourth Circuit. The defendants argue that limiting online access to lawyers and certain government agencies allows the courts to better prevent against fraud and misuse of “private, sensitive information let out into the world and limiting the potential for widespread data harvesting which is often done by bots.” On its surface, this seems a noble argument, but it fails to consider that: 1) the information online is already non-confidential in nature, with any sensitive information required to be redacted by filers of the documents; 2) any member of the public can already access these documents in person; and 3) openness has worked well for the 38 other states that have functional, non-compromised online systems in place that allow widespread public access. Protect The 1st is particularly sensitive to the protection of online data – but, as the amici point out, Virginia’s argument is speculative at best, showing no evidence of data harvesting by bots or anyone else. Restricting access to OCRA based on assumptions about how certain non-favored speakers may use that information is plainly not content-neutral. Instead, as amici contend, it “amounts to unconstitutional speaker-based discrimination that demands strict scrutiny.” Further, as other courts show, less restrictive means of protecting information in court documents obviously exist – certainly less restrictive than denying access to public documents. Most importantly, fundamental press freedoms are at stake here. “…[I]n denying the press and the greater public access to OCRA,” amici write, “the Non-Attorney Access Restriction infringes the public’s presumptive constitutional right of contemporaneous access to civil court records.” Journalists depend on remote, online access to report on cases of public concern in a timely manner. “If not reversed,” the brief declares, “the District Court’s order will hamper the ability of the news media to report on court proceedings of public interest in Virginia and around the country.” Courthouse News Service, the Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press and their fellow amici are right in urging the Fourth Circuit to overturn the lower court’s grant of summary judgment in this case. We’ll be following future developments closely. Settlement Spurs Civics Lesson for Law Enforcement Last month, Los Angeles County reached a $700,000 settlement agreement with a radio journalist who was accosted and arrested by police while attempting to document law enforcement’s response to a local protest. It’s a significant sum that will deter future government hostility against reporters who are simply doing their jobs.

Most critical of all, the settlement includes new training requirements for law enforcement personnel about the media and the First Amendment, as well as policies and laws governing interactions with the press. We wrote recently about a series of similar incidents across the country in which government officials have misused their authority to punish journalists. This includes an FBI raid of a Florida journalist’s home, a retaliatory raid in Kansas preceding an elderly publisher’s death, and the arrest of a publisher in Alabama for lawfully reporting on leaks from a grand jury about the mishandling of COVID funds. Even in Washington, D.C., the media is not immune from such abuses. Consider the case of CBS News Correspondent Catherine Herridge, who was ordered by a U.S. district court judge to reveal the identity of confidential sources she used for a series of 2017 stories. She has, laudably, refused to do so, risking imprisonment in the process. In Herridge’s case – and in many other similar cases – the passage of the Protect Reporters from Exploitive State Spying (PRESS) Act would be a major step in the right direction, limiting the ability of prosecutors to expose the sources and notes of journalists in federal court. More fundamentally, however, what we need most is better education and constitutional literacy. That’s why the recent events in Los Angeles County are so important. In that case, LAist journalist Josie Huang briefly filmed sheriff’s deputies arresting a protester when she was ordered to “back up.” Before Huang could respond, she was brutally slammed to the ground and subsequently taken to jail and charged with obstructing a peace officer. Outcry was swift, with the Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press and 65 other media organizations quickly mobilizing to demand that charges against Huang be dropped. The district attorney’s office, likely recognizing the unconstitutional actions of the sheriff’s deputies, declined to prosecute. A court later found her factually innocent of the charges. The resolution in Los Angeles is a good outcome, but it shouldn’t take a crisis to require law enforcement officers to have some semblance of understanding of the First Amendment. With any luck, the Huang incident can serve as a lesson – in civics as much as in consequences. That a free press is integral to free speech was obvious to the founders, who guaranteed both in the First Amendment. But is it so obvious today? Under both Democratic and Republican presidents, federal investigators have helped themselves to the private records of the AP, CNN, The Washington Post, and The New York Times, as well as those of activist journalists on both the left and right.

In Kansas, police raided a small-town newspaper over a minor story involving public records and a DUI. The police confiscated newsroom computers containing reporters’ notes and source materials and putting the very existence of the paper at risk. Fortunately, Kansas has a state press shield law that grants media the right to keep source identities confidential. Journalists enjoy no such protections at the federal level. It is not clear what recourse, for example, Tampa-based journalist Tim Burke has after the FBI stormed his home in May, confiscating his computer, cellphone, and information on multiple stories and their sources. If trust is the coin of the realm, then the federal government’s coinage is debased. The Pew Research Center reports that only 2 percent of Americans trust the government in Washington to do what is right “just about always.” Only 19 percent believe the government acts correctly “most of the time.” To be sure, cynicism about government results from spectacular failures of competent governance. The cynicism also reflects the loudly proclaimed belief by political leaders that the other party, once in control, will weaponize investigations and prosecutions, while thumbing the scale for its friends and allies. While these fears are sometimes overstated, the solution is not to weaponize government for one side against the other, but to hold government accountable to everyone. One of the best ways to restore trust is to protect the freedom of journalists to do their jobs. From Watergate to the Pentagon papers, to the depredations of Harvey Weinstein, to the roiling controversies of our day, journalists’ revelations have been enabled by whistleblowers, brave men and women willing to risk it all to reveal wrongdoing. All states save Wyoming offer greater journalist protections than the federal government. South Carolina, to cite just one of 49 examples, enacted a press shield law in 1993 to protect journalists from being compelled to divulge their sources. The preface to the law boldly states: “The General Assembly finds that it is vital in a democratic society that the public have an unrestricted flow of information on matters of concern to the public and that the threat of compelled testimony … interferes with the free flow of information to the public.” The good news is that as events spin into overdrive in the nation’s capitol, congressional leaders in both parties are coming to see the wisdom of following South Carolina’s example. They are ready to temper government actions to protect journalists and press freedom from overweening federal prosecutors by passing a federal press shield law, the Protect Reporters from Exploitive State Spying (PRESS) Act. The PRESS Act protects both journalists and their sources. The latter is important, because whistleblowers need the assurance that the reporter with whom they speak in confidence cannot be compelled to betray their trust. The PRESS Act offers that promise by establishing a federal statutory privilege shielding journalists from being compelled to reveal confidential sources. It would also block attempts to compel disclosure of account information from communications services used by reporters. In 2007 and again in 2009 as a member of the House, Protect The 1st Senior Policy Advisor Rick Boucher was the primary author of the forerunner to the PRESS Act. He saw it pass the House twice with large bipartisan majorities, and then die – as so many good bills do – in the Senate. This time, the stars seem to be aligning in the Senate for passage of the PRESS Act. Lindsay Graham, South Carolina’s senior senator and the Ranking Member of the Judiciary Committee, is cosponsoring the measure. Sen. Graham joins a strong bipartisan team that includes Senate Judiciary Chairman Dick Durbin (D-IL), Sens. Ron Wyden (R-OR) and Mike Lee (R-UT). The PRESS Act also enjoys strong bipartisan leadership in the House from Rep. Kevin Kiley (R-CA) and Rep. Jamie Raskin (D-MD). House support ranges from conservative Rep. Jim Jordan (R-OH), Chairman of the House Judiciary Committee, to liberals like former committee Chairman Jerry Nadler (D-NY). During the last Congress, the House approved the PRESS Act by a bipartisan, unanimous voice vote. The acceptance of press shield laws by 49 states demonstrates sweeping public support for freedom of the press. At a time when trust is scarce, wouldn’t it be refreshing to see national leaders in both parties pass a popular measure that enhances a fundamental freedom and holds government accountable? Across America, from small towns to Washington, D.C., officials are misusing their authority to punish journalists.

In April, Protect The 1st reported that on at least two occasions, agents at ICE used a legal tool meant to aid in criminal investigations to pressure news organizations into revealing information about their sources. In May, we reported that the FBI raided the home of a journalist, seizing his computer, hard drives, and cellphone, after he published embarrassing outtakes of a Fox News interview – which had already been posted online. In August, Protect The 1st reported on the death of an elderly publisher in rural Kansas shortly after local police raided her home. In November, we reported on an Alabama district attorney who arrested a publisher and a reporter for reporting on leaks from a grand jury about the mishandling of Covid funds. Also this month we reported on the “ticketing” of a local journalist by Calumet City, Illinois, for having the temerity to send 14 emails over a nine-day period to city officials seeking comment on local flooding. The First Amendment is clear, but the trend against it continues in the wrong direction, with such incidents piling up recently. The question is: why? We believe these clumsy attempts to punish the press can only be the result of the poor civics education of these officials in their youth. It also reflects an increasing appetite by politicians of all stripes to weaponize the law. There is, fortunately, a bulwark against such local abuses. Forty-nine states have passed press shield laws that protect journalists and their sources. Yet Congress has not enacted a national shield law to protect reporters from federal prosecutors and courts. The Protect Reporters from Exploitive State Spying (PRESS) Act would limit the ability of prosecutors to expose the sources and notes of journalists in federal court. The PRESS Act passed through the House Judiciary Committee to the full House by a unanimous 23-0 vote in July. The PRESS Act would have made a difference in the case of CBS News senior correspondent Catherine Herridge who, earlier this year, was ordered by a judge for the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia to reveal the identity of a confidential source or sources she used for a series of 2017 stories published while she worked at Fox News. Her stories covered Chinese-American scientist Yanping Chen, subject of a federal counterintelligence probe. Chen subpoenaed Herridge and Fox News, with the hope of unmasking the source(s) for the stories. Herridge has since refused to reveal her source(s), and Chen’s lawyers are asking the judge to hold the journalist in contempt of court. The Herridge case is all the more reason for a federal shield law in the form of the PRESS Act. No federal legislation, however, can change the dysfunctional, constitutionally illiterate, and illegal acts by government officials against reporters. That is not a matter of law, but of culture and education. Press freedom is strong only when people and the powers that be understand it and respect it. Most reporters aspire to superlatives like “dogged,” “tenacious,” and “persistent.” In Calumet City, Illinois, such traits are seen by some as a liability. In fact, they can you ticketed. That’s what happened recently to Daily Southtown reporter Hank Sanders, who was cited for “interference/hampering of city employees” after sending 14 emails over a nine-day span to a handful of city officials seeking comment about flooding in the small town.

Sanders had previously reported that outside consultants told Calumet City officials that their stormwater infrastructure was in poor condition prior to historic flooding that occurred in September. Subsequently, Sanders continued his efforts to get to the bottom of the story – which apparently did not sit well with city officials like Mayor Thaddeus Jones, who was listed as a complainant on Sanders’ citation. Likewise, Sanders’ persecution at the hands of smalltown city officials didn’t sit well with the editorial board of the Chicago Tribune (which shares a parent company with the Daily Southtown). In an editorial, they called the city’s behavior “clownish.” Executive editor Mitch Pugh went a bit further: “[Calumet City’s actions] represent a continued assault on journalists who, like Hank, are guilty of nothing more than engaging in the practice of journalism. From places like Alabama to Kansas to Illinois, it appears public officials have become emboldened to take actions that our society once viewed as un-American. Unfortunately, in our current political climate, uneducated buffoonery has become a virtue, not a liability, but the Tribune will vigorously stand up for Hank’s right to do his job.” There is no room to be dismissive of this event. It is yet another recent example in a worrying trend in small-town America where power-drunk officials attempt to punish reporters for committing the act of journalism. One instance to which Pugh refers we recently wrote about: a small town publisher and reporter were arrested in Alabama for reporting on a grand jury leak about the alleged mishandling of COVID relief funds in a local school district. The other we wrote about in August – police in Kansas raided the Marion County Record in an effort to track down an informant who revealed information about a local restauranteur’s DUI. In that instance, the paper’s 98-year-old co-owner died a day after her home was raided. The Calumet City controversy has a happier ending. On Nov. 6, the city attorney – who seems roundly embarrassed by the whole ordeal – sent a letter to Tribune lawyers dropping the citation. And the Tribune itself seems to be enjoying a deserved bout of schadenfreude over the city’s capitulation. The trend line, however, is declining respect for the First Amendment and a free press. Reporters must feel free to pursue stories of public interest without fear of reprisal. Sanders himself perhaps put it best: “I will continue to be reaching out to the correct department or employee for comment when I want a comment from that department or employee. To do otherwise is unethical.” Forbids Newspaper from Reporting on Crime, Seizes Cellphones from School Board Members and Publisher Much digital ink has been spilled about the arrest of a small-town publisher and reporter in Atmore, Alabama, for reporting on a grand jury leak about the alleged mishandling of COVID relief funds in the local school district. But events surrounding the arrests of these two journalists should be of even greater concern to First Amendment advocates.

While Alabama law makes it a crime for grand jurors, witnesses, and others directly involved in a grand jury proceeding to disclose information from these secret hearings, this prohibition does not include journalists. Moreover, a long line of U.S. Supreme Court precedents, harking back to the Pentagon Papers, make it clear that journalists can report leaks, even when the leak is illegal. This is judged necessary for freedom of the press. Time and again, such reporting has broken loose the logjam of secrecy, incompetence, and inside-dealing that often hardens inside powerful institutions. But the plain facts and the law did not stop Escambia County District Attorney Stephen Billy from charging Atmore News publisher Sherry Digmon and reporter Don Fletcher with a felony charge of reporting grand jury information, carrying a penalty of between one to three years imprisonment and a fine of $5,000. Worse, from a constitutional perspective, are bail terms that prohibit the journalists from reporting on “ongoing criminal investigations.” In this one brilliant move, District Attorney Billy ventured from criminalizing reporting into the worst offense against free speech – prior restraint. “The bail terms would be unconstitutional even if they only restricted the journalists from further reporting on the grand jury investigation of the school district, especially when there was no legal or constitutional basis to punish that reporting in the first place,” said Seth Stern, director of advocacy at the Freedom of the Press Foundation. “That overbreadth turns an already flagrantly unconstitutional gag order into a fundamentally un-American attempt at retaliatory censorship to silence the free press. Everyone involved should be ashamed of themselves.” The Atmore News today posts a straightforward, factual account of the arrests of its publisher and reporter. Could that be construed by the district attorney as a bail violation? It is not clear. And when legal standards are not clear, the free practice of journalism suffers. In a separate action, District Attorney Billy dispatched sheriff’s deputies with search warrants to seize the cellphones of four members of the Escambia County Board of Education who voted not to renew the contract of the local school superintendent. One of the board members was publisher Sherry Digmon. The stated purpose of the raid was to investigate a possible telephone violation of Alabama’s Open Meetings Law by the four board members, even though violations are a civil matter under Alabama law. It is not a crime. It would be easy to dismiss this case as an outlier by a bumbling local district attorney. As the Dude says in The Big Lebowski, “this aggression will not stand, man!” It is all but certain District Attorney Billy and his case will not fare any better than did that of the small-town police chief in Kansas who raided the local newspaper and seized all its equipment over the reporting of a local businesswoman’s DUI record. But even when intimidation fails, the hassle and embarrassment of an arrest and the confiscation of phones and equipment cannot be far from the minds of local journalists these days. That such cases are beginning to pop up around the country is one more sign that America is drifting away from our constitutional moorings. An FBI raid on the home of a Tampa-based journalist, and the seizure of his computer, hard drives, cellphone and all they contain, is raising questions about the fidelity of the Department of Justice to a year-old revision to its News Media Policy announced by Attorney General Merrick Garland. Under that policy, the Department is forbidden from using compulsory legal processes to obtain the newsgathering records of journalists, except in extreme circumstances.

Now a wide spectrum of press freedom and civil liberties organizations are asking the Department of Justice to provide transparency about this FBI raid in May. The FBI executed its search warrant at the home of journalist Tim Burke, which he shares with his wife, Tampa city councilwoman Lynn Hurtak. The credibility of this extreme action is highly questionable, leaving the Department to explain how this ransacking of a journalist’s home and seizure of his devices differs from the now-widely ridiculed police raid on a newspaper in rural Kansas. Burke is a former staffer of The Daily Beast and Deadspin. The reporting that put him in crosshairs of the FBI ran in Vice News and Media Matters for America (MMFA). Yet many civil libertarians are voicing suspicions, based on a government response brief, that DOJ may not regard Burke as a valid journalist worthy of the enhanced protections afforded reporters under the Privacy Protection Act of 1980. What we can say is that the FBI criminal investigation involves purported “hacking” of Fox News under the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act and wiretapping laws. Burke reported on embarrassing outtake videos from former Fox News commentator Tucker Carlson’s interview with Ye – formerly known as Kanye West – which were then published by Vice News MMFA. In the outtakes, Ye comes across as deranged and in serious need of help, voicing one ugly, juvenile antisemitic conspiracy theory after another. Carlson cut these lengthy and offensive rants from the interview, making Ye appear far more thoughtful than he is. Carlson concluded his show by saying that Ye is “not crazy” and is “worth listening to.” It is easy to see why even after Fox News fired Carlson that it would find these outtakes embarrassing. Fox News has since been intent on identifying the source of the leak. Fox sent a letter to MMFA earlier this month, demanding the outlet stop airing videos that were “unlawfully obtained.” MMFA president Angelo Carusone responded: “Reporting on newsworthy leaked material is a cornerstone of journalism ... Like any respectable media outlet, we won’t discuss confidential sourcing of any of our materials.” For his part, Burke says he obtained the unaired portions of the Tucker Carlson interview with Ye by visiting a publicly available website used to transmit live feeds of broadcasts. Fox News had apparently uploaded the video to the public site without encrypting it or keeping anyone from downloading it. Burke did use a user ID and password for a “demo account” provided to him by a source. That source, Burke says, found the credentials on a public website, without any restriction on their use. Given these facts suggest an impingement on the First Amendment and the practice of journalism, Attorney General Garland should direct the Department of Justice to provide a degree of transparency in this case. Among questions that need to be answered:

Burke claims he obtained the outtakes from a public source, with help from a source who knew how to access publicly posted credentials to download the raw interview.

There may be legitimate answers to some of these questions that put the Department’s actions in a better light. If they do not, however, DOJ and the FBI run the risk of resembling the bumbling, Barney Fife-like police chief in Kansas who raided a newspaper and, by the way, just resigned. The Protect Reporters from Exploitive State Spying, or PRESS Act, now has strong bipartisan support, with 20 co-sponsors. This milestone comes shortly after the bill received unanimous support from the House Judiciary Committee back in July.