|

Protect The 1st has stood fast to protect the First Amendment rights of Americans to the free exercise of religion – for Native Americans seeking to hold on to lands sacred to their worship, to the right of religious schools to participate in tuition assistance programs, to the right of a high school coach to pray after a game.

The First Amendment also protects us from the imposition of religion as well. Balancing the free exercise clause of the First Amendment is a preceding clause that prohibits the establishment of a religion. It is instructive to see what a violation of that sort looks like. A public high school in Huntington, West Virginia, sent students to the school’s auditorium in mid-morning. They were told to raise their arms and pray. An evangelical preacher told the students to give their lives over to Jesus and follow the Bible or else face going to hell. This event, organized by the school’s chapter of the Fellowship of Christian Athletes, was supposed to be voluntary. But many students were told it was mandatory. At least one Jewish student tried to leave, only to be told by his teacher that he was locked inside. Later, nearly a dozen students and parents sued the local school board, superintendent and principal in federal court asking for $1 per plaintiff, attorneys’ fees and a permanent injunction against future proselytizing events. To their credit, the school system superintendent and high school principal acknowledged that this event was not handled properly and would not be allowed to happen again. “School authorities have said that the event was improperly handled and offered assurances that similar mistakes would not occur in the future,” said Rick Boucher, former Member of Congress and Protect The 1st senior policy advisor. “But this event is a teaching moment that demonstrates that the First Amendment – while assuring freedom to worship – also protects against compelled religion.” When the government widened U.S. Highway 26 in Eastern Oregon, it took care to protect wetlands and avoid encroaching on a tattoo parlor. But when it encountered The Place of the Big Trees, an ancient stone altar and grove of trees sacred to the Yakima Nation and the Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde, the government deployed its bulldozers and destroyed the site.

After the destruction, the elders of these tribes appealed to the government to return the rocks that made up their altar and replant the medicinal plants they had uprooted. The U.S. District Court for the District of Oregon instead found that the U.S. Federal Highway Administration had not violated the religious rights of the tribes under the Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA). A court panel further did not see that it had the authority, or a need, to attempt remediation. Now the Protect The First Foundation is joining with the Jewish Coalition for Religious Liberty, the Sikh Coalition and the American Islamic Congress to stand up for RFRA and the rights of religious minorities. The coalition filed an amicus brief Tuesday urging the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals to hear the case and consider ways to remediate and restore the site. The coalition demonstrated that “when the government cannot grant a religious claimant’s ideal accommodation, it bears the burden of proving that there are no possible remedies.” As it stands, the message of the lower court and the government is, essentially, to like it or lump it. With secular claims in the Ninth Circuit, the fact that a harm has been completed does not render it moot. The lower panel violated this precedent in creating a lower standard for religious plaintiffs than for secular plaintiffs. Simply put: No crying over spilled milk. Overall, the panel shrugged off the law’s requirement that it explore other ways to rectify the injury the government inflicted. The brief states: “If left standing, the panel decision would gut RFRA, turning it from a landmark ‘super statute’ – passed to provide robust remedies for religious believers like plaintiffs who are prevented from exercising their faith – to a statute only occasionally able to protect religious belief.” Finally, somehow the lower court ruling found that it lacked the authority to craft a case-specific remedy as required by RFRA. In so doing, the panel created a precedent that hinders RFRA’s ability to protect the very people it was designed to help – religious minorities. “These concerns are all the more prevalent when it comes to non-Western and Indigenous faiths,” the brief states. “In contrast to mainstream religions, which ‘already enjoy de facto protection’ through their ability to influence the political sphere … many minority faiths must turn to the courts for protection. But in doing so, these groups face a significant obstacle: explaining the nature of their beliefs and injuries to a judiciary that is mostly drawn from mainstream faith communities.” The coalition is dismayed that the panel believes it cannot summon the authority to order the government to replace a one-and-a-half-foot stone altar, replace trees, or remove an embankment. “It is difficult to understand the actions of the government and the courts except as willful ignorance and outright contempt for the tribes’ faith,” said Gene Schaerr, general counsel of The Protect The First Foundation. “For all Americans, there is a danger in allowing courts to ignore RFRA’s broad grant of authority to redress government interference with religious practice. The Ninth should hear this case to guarantee the right of free exercise of religion for all Americans.” Federal Judge James Ho spoke truth to power this Tuesday when he switched from his prepared remarks about judicial originalism at Georgetown University Law School to speak up for the embattled scholar Ilya Shapiro.

Shapiro has begun his tenure as director of the law school’s Center for the Constitution on suspension. The reason? This libertarian-conservative had sent out a tweet questioning the racial lens that President Biden had imposed on his upcoming choice for a Supreme Court nominee. Shapiro criticized the president’s decision to only consider black women as potential nominees. Shapiro’s tweets included the inartful words “lesser black woman” in comparison to a male candidate of color that Shapiro considered the best possible choice. Shapiro apologized and deleted his tweets. After pressure from activist groups, Georgetown placed Shapiro on administrative leave, consigned to the antechamber of the cancelled. Georgetown’s actions seem particularly unprincipled to many considering that one of its faculty had her speech rights stoutly defended by the university after she tweeted that supporters of Brett Kavanaugh’s Supreme Court nomination “deserve miserable deaths,” should be “castrated” and have their corpses fed to swine. It is against this background that Judge Ho switched gears from his original speech and spoke extemporaneously about free speech and cancel culture before a crowd of law students and faculty. Judge Ho spoke movingly of facing discrimination as a Taiwanese-American law student and young lawyer. But, Judge Ho said, “cancel culture is not just antithetical to our constitutional culture and our American culture … [it is] completely antithetical to the very legal system that each of you seeks to join.” But that antithesis is becoming the rule in the academy. The search for an offense in a target’s words is turning into an academic reign of terror. In another a case, in a law class exercise on Civil Procedure II, University of Illinois at Chicago law professor Jason Kilborn included – for the tenth year in a row – a hypothetical employment discrimination case that mirrors real-world tensions. This case involved the use of redacted racial slur and a redacted sexist slur. The actual words were not used in the exercise. For this crime, Kilborn lost his annual pay raise and was tasked to eight-weeks of sensitivity training with 20 hours of course work, five “self-reflection” papers, and weekly 90-minute sessions with a diversity “trainer.” George Will wrote: “Could those who concocted this sentence ever recognize their kinship with the moral purifiers of Cambodia’s Khmer Rouge?” At the very least, such persecution certainly justifies the use of an overused word, “McCarthyism.” The defenestration of innocent scholars is reaching obscene proportions. Judge Ho shows that the time of politely tiptoeing around such controversies is over. Supreme Court Short Listers Stand in Stark Contrast on First Amendment’s Ministerial Exception2/12/2022

PT1st will report on the First Amendment records of the three candidates most often mentioned as making up President Biden’s “shortlist” to replace Justice Stephen Breyer on the U.S. Supreme Court – Judge Ketanji Brown Jackson of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia, Leondra Kruger, California Supreme Court Justice, and J. Michelle Childs, a federal district judge in South Carolina. In this piece, PT1st examines an opinion written by Judge Childs and compares it with a litigating position taken by Justice Kruger when she served in the Department of Justice. Of the Justices appointed by Democratic presidents, Justice Stephen Breyer is probably the friendliest to religious claims. An article published earlier this week, for example, explained that Breyer voted in favor of religious liberty in nine of the last 13 religious liberty cases.

With Justice Breyer’s pending retirement from the Supreme Court, President Biden has the chance to pick a nominee who is as good or better than Justice Breyer on First Amendment issues. As Justice Byron White famously said, every new Justice makes a “different court,” even if she is replacing someone she largely agrees with. How might the newly comprised Supreme Court be a different court on the religious cases that so regularly come before the Court? At least with respect to one issue, the First Amendment’s ministerial exemption, the choice between Justice Kruger and Judge Childs could make all the difference. The ministerial exemption, first recognized by the Supreme Court in 2011 in a case called Hosanna-Tabor v. EEOC, forbids the government from contradicting “a church’s determination of who can act as its minister.” In that case, then-Assistant to the Solicitor General Leondra Kruger argued that the First Amendment’s Religion Clauses have nothing to say about a church’s decisions with respect to its employees, a position that even the liberal Justice Elena Kagan considered “amazing” — and not in a good way. (You can listen to the exchange here, starting at 40:30.) Kruger’s position lost, unanimously. Earlier this week, in an attempt to distance Kruger from that argument, the former Solicitor General Donald Verrilli said that the call to make that (losing) argument was his alone. If it’s true that Kruger was just following orders, then we don’t know how she’d rule on ministerial exception cases that might come before her. It is entirely possible that a Supreme Court Justice Kruger would have a more expansive view of the First Amendment’s protections than she argued for in Hosanna-Tabor as an Assistant to the Solicitor General. But really, we just don’t know. What we do know is how Judge Childs applied the ministerial exemption in a case after Kruger’s unanimous loss. In a case called Yin v. Columbia International University, Childs found that a teacher at Columbia International University (CIU)—a “multi-denominational Christian institution of higher education dedicated to preparing world Christians to serve God with excellence”—was a minister and, accordingly, could not recover from her employer for alleged violations of civil rights laws. We think that Judge Childs applied the ministerial exception correctly in that case. The teacher in that case, Yin, “required her students to pray together,” “integrated biblical materials inter her courses, and prepared students for ministry roles.” To Judge Childs, these clearly religious acts “weigh[ed] heavily … in favor of applying the ministerial exception.” Other factors, to be sure, weighed against finding that Yin was a minister. She was the Director of Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages Program at CIU, a nominally secular title. And Judge Childs found that Yin didn’t understand herself to be a religious leader or a minister, notwithstanding her overtly religious activities. But Judge Childs gave those considerations less weight, looking more at what Yin did at CIU than anything else. Only a few years later, a majority of the Supreme Court that included Justice Breyer decided Our Lady of Guadalupe v. Morrissey-Berru. In that case, the Court upheld Child’s understanding of the ministerial exception when it recognized that, for purposes of the ministerial exception, “[w]hat matters is ... what an employee does.” Judge Childs is to be commended for understanding the paramount importance of an employee’s actions long before the Supreme Court itself made that importance clear. The position that Justice Kruger advanced in Hosanna-Tabor, namely that the Religion Clauses say nothing about the relationship of religious organizations with their ministers, differs sharply from how Justice Breyer voted both in Hosanna-Tabor and in Our Lady of Guadalupe. And the position couldn’t be more different from how Judge Childs applied Hosanna-Tabor in Yin. If Justice Kruger is the nominee, PT1st hopes that members of the Senate Judiciary Committee will question her to get to the bottom of her position on the ministerial exemption. In the meantime, the available evidence shows that Judge Childs will likely vote like Justice Breyer has voted, at least in ministerial-exemption cases. Are we seeing the beginnings of a pivot from cancel culture to engagement culture?

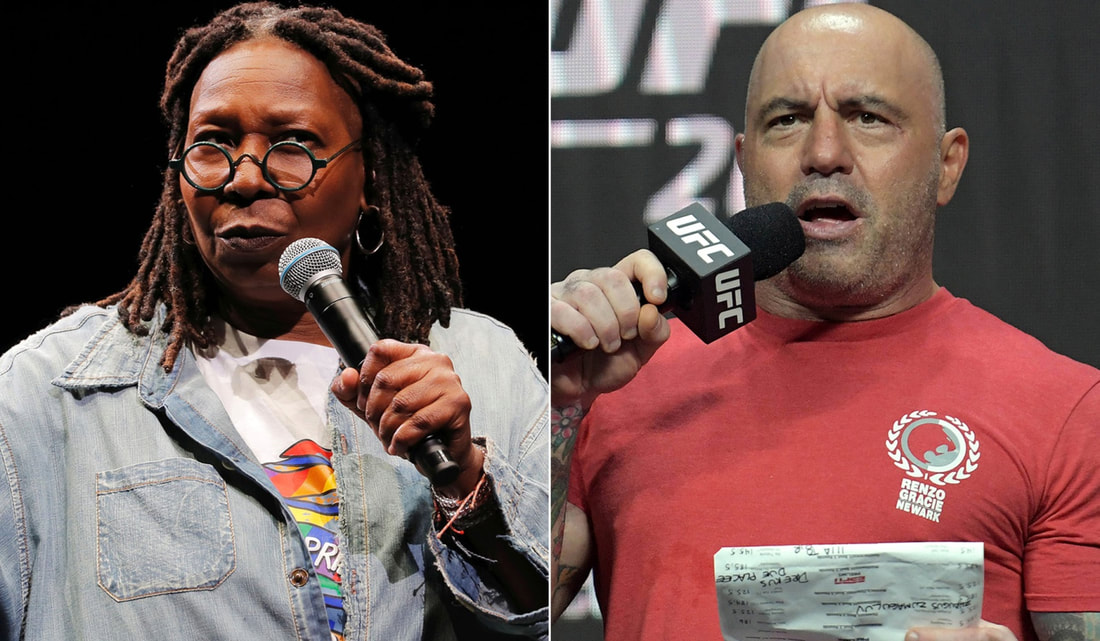

Several major cancellations that before would already be done are, instead, frozen in mid-air. Spotify is visibly sweating bullets at the prospect of having to cancel Joe Rogan over Covid misinformation and racist slurs in the service of bad jokes. This can’t be an easy decision. Rogan’s podcast dwarfs the ratings of the most highly rated shows of the major television networks. And Rogan is a media giant because he is so different, exhibiting a naïve curiosity, a willingness to question anything and change his mind in the quest for the truth – and admit when he’s gotten something wrong. Whoopi Goldberg, who made an offensive remark about the Holocaust, has been cast out from The View for a fortnight to reflect on her verbal crime, as if she were an out-of-control toddler in need of a time-out. Illya Shapiro, the Georgetown scholar who in one inartful tweet questioned President Biden’s racial filter for his Supreme Court nominee, is now under “investigation” by his putative employer, Georgetown University. Maybe one or all will eventually be cancelled. But what if we instead turned to radical engagement? Why not have Whoopi Goldberg explain to Joe Rogan why a racial expletive told in jest from a white podcast host is still wounding? Why not have someone from the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum explain to Whoopi what was so offensive about her remark that the mass murder of Jews was “not about race”? Why not have CBS’s Dr. Tara Narula walk Rogan through his Covid claims and give skeptics something to think about? This is not to say that there are no cancel-worthy statements. And companies, whether Spotify or Facebook, do have their own right under the First Amendment to drop any speaker they choose. But, as David French argues in a brilliant essay in The Dispatch: “I have never in my adult life seen anything like the censorship fever that is breaking out across America. In both law and culture, we are witnessing an astonishing display of contempt for the First Amendment, for basic principles of pluralism, and for simple tolerance of opposing points of view.” Those who speak for a living will, over the course of years, eventually say something stupid or offensive. The problem is that critics now eagerly await their missteps so they can hit the ‘cancel’ button and eject those whose views they don’t like. As French points out, this tactic is now coming from the right as well as the left. In some cases, the honest intent of cancellation is to impose a kind of cultural hygiene. The problem is that culture doesn’t work that way. Cancellation leaves silence and cancelled speech – especially if it is ugly – acquires a kind of outré glamor for the impressionable. Apologies are taken as evidence of guilt instead of honest remorse. Most of all, the public loses the opportunity to hear real discussions. On the other hand, an engagement approach would be good for our culture. And not incidentally, it would create the kind of drama that would be good for ratings. The Commonwealth of Virginia is breaking away from eight other states that support the state of Maine’s exclusion of religious private schools from a tuition-assistance program.

Carson v. Makin, pending now before the U.S. Supreme Court, raises the question whether the First Amendment’s Free Exercise Clause requires Maine to allow, or disallow, religious private schools to participate in a private-school tuition program for children in rural areas. Maine argued before the Court that tuition-assistance funds can go to religious schools if those schools do not provide “sectarian” or religious instruction. A statement from Virginia’s Solicitor General Andrew Ferguson highlights the absurdity of this argument: “Maine’s proposed distinction between impermissible discrimination on the basis of religious status and permissible discrimination on the basis of the religious use of funds is illusory and finds no support in the text of the First Amendment.” Ferguson then quotes a 2020 Supreme Court opinion in a landmark religious liberty case, Espinoza v. Montana Dep’t of Revenue: “[W]hether [the exclusion] is better described as discriminating against religious status or use makes no difference: It is a violation of the right to free exercise either way …” Protect The 1st urges the Justices take a moment to read this crisp, succinct memo from Virginia as they make their decision. Millions of people around the world were outraged when a Tennessee school district thoughtlessly banned the Pulitzer-Prize winning graphic Holocaust novel Maus on World Holocaust Remembrance Day.

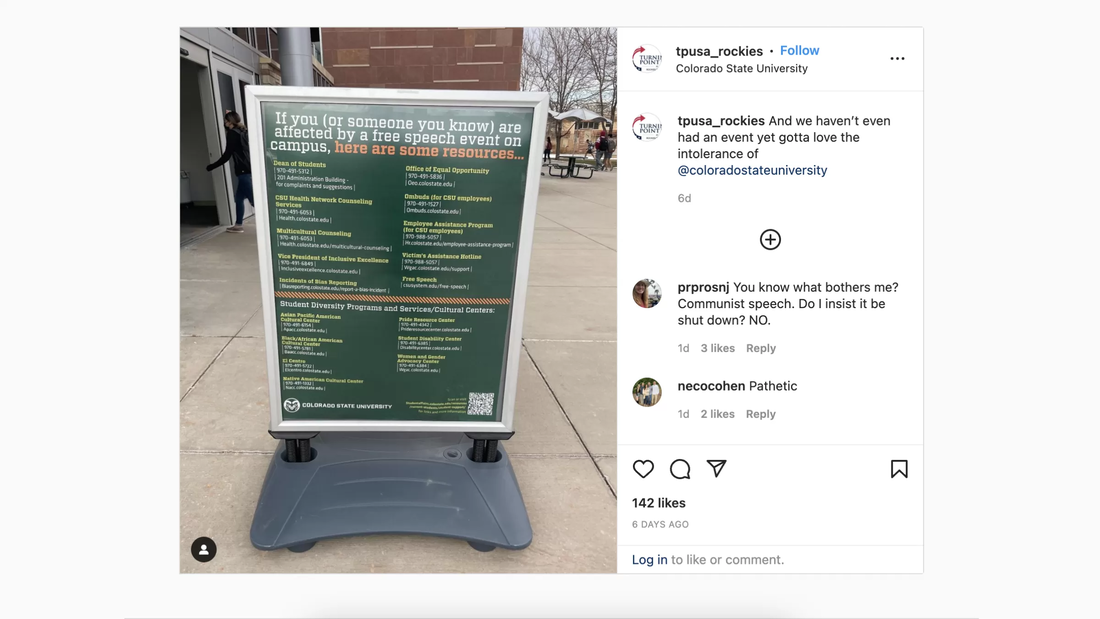

We should take heart, however, that this action immediately reaffirmed the karmic law of the internet known as the Streisand Effect. This phenomenon was named after the great singer-actress Barbra Streisand, who dispatched high-powered lawyers to issue legal threats and cease-and-desist letters against an obscure website that posted pictures documenting erosion along the California coastline. Among the 12,000 images posted by the California Coastal Records Project were aerial images of Streisand’s home. Claiming that merely including those images in a database somehow invaded her privacy, Streisand sought $50 million in damages. At the time, only six people had downloaded the images. Streisand lost in court and was required to pay the defendant’s legal fees. In only one month, because of the publicity her lawsuit inspired, more than 420,000 people visited the website. What is now happening with Maus is only the latest demonstration of the Streisand Effect: In a democracy, attempts at repression generate publicity. And nothing makes intellectual property shinier than trying to forbid it. Commands like don’t read this book!, of course, make you want to read the book. (By the way, don’t read our blog!) Shortly after the school board in McMinn County, Tennessee, voted unanimously to ban Maus (first published in the Eighties) from its eighth-grade curriculum, The Complete Maus anthology hit No. 1 on Amazon’s bestseller list. The Streisand Effect, however, only works against ham-handed attempts to stifle speech. The danger we face today is the censorship we cannot see. Such hidden censorship, whether by universities, governments, large social media platforms, or private parties – quietly tucks away speech deemed too upsetting to established truth. When that happens, we’re all harmed. This image from Colorado State University is making the rounds on social media and in Reason Magazine.

This sign helpfully directs a student to the many offices and resources available to protect her or him from “a free speech event.” Either this sign was created with an astonishing lack of self-awareness, or the authors are fully self-aware of what they are saying and are bent on redefining “free speech” as a roaming threat to students’ well-being. Whichever you choose, it is enough to make George Orwell spit out his nice cup of tea. This image comes on the heels of the story about Georgetown University’s pending defenestration of Ilya Shapiro, the scholar who was today to assume a job as executive director of the Georgetown Center of the Constitution. As reported by journalist Bari Weiss, Shapiro posted a tweet a few days ago that criticized the racial and gender category President Biden set for his Supreme Court nominee. And as is characteristic of so many Twitter compositions, Shapiro blundered with his thumbs. He contrasted a male candidate he considers to be the best possible choice, Judge Sri Srinivasan, with anyone else, including, in his words, “a lesser black woman.” The blowback was immediate, and a mob quickly called for Shapiro’s relationship with Georgetown to be terminated. To be sure, Shapiro’s tweet shows that the authors of the Colorado State University sign are not entirely wrong. Free speech between well-meaning people can sometimes hurt. That’s a risk we run in the fast, free exchange of ideas, especially in casual environments like Twitter. But at Georgetown, one doesn’t have to be particularly well-meaning to be defended by the university, provided the speech comes with the appropriate ideological slant. As Weiss recounts, Georgetown professor Carol Christine Fair had her free speech rights affirmed after she tweeted that U.S. senators who supported Judge Brett Kavanaugh’s nomination to the Supreme Court “deserve miserable deaths” and that “we” should “castrate their corpses and feed them to swine.” In the aftermath of this tweet, Georgetown vigorously supported Fair, noting that it allows ideas that “may be difficult, controversial or objectionable” from faculty members in their private capacity. Shapiro, for his part, quickly deleted his careless tweet and sent an open letter apologizing for his inartful language. But even after Shapiro’s apology, the calls for his termination continued. As Weiss reports, “these days, sincere apologies do not function as expressions of regret but as confessions of guilt.” Shapiro is now on leave while the university investigates his tweets. The ever-alert Foundation for Individual Rights in Education (FIRE) has brought 50 faculty members and higher-education leaders from across the ideological spectrum to Shapiro’s defense. But the overall lesson to be drawn from this story is that if you have views that go against the grain on campus, you had better be exact in every comment. A slip of the tongue or an inartful tweet can end one’s career. On the other hand, if your views are in line with the prevailing ideology, you can call for U.S. senators to suffer miserable deaths and castration. Interestingly, Fair responded to questions about Shapiro by saying: “In general, I believe that the only response to speech one doesn’t like is more speech and I decry cancel culture on any side.” Although intemperate in her own language, Fair is laudable in her defense of the freedom of speech in the Academy. Protect The 1st will follow Shapiro’s case, as well as the free speech rights of others – left, right and center. |

Archives

June 2024

Categories

All

|

ABOUT |

ISSUES |

TAKE ACTION |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed