|

Communities have the power to pass laws that protect vulnerable minors from clearly inappropriate material, even in cases where adults have a First Amendment right to view and distribute that material to each other. But such laws have to be precise in how they enforce restrictions. And, one would hope, they’d include solutions to actual problems – not just a response to political passions.

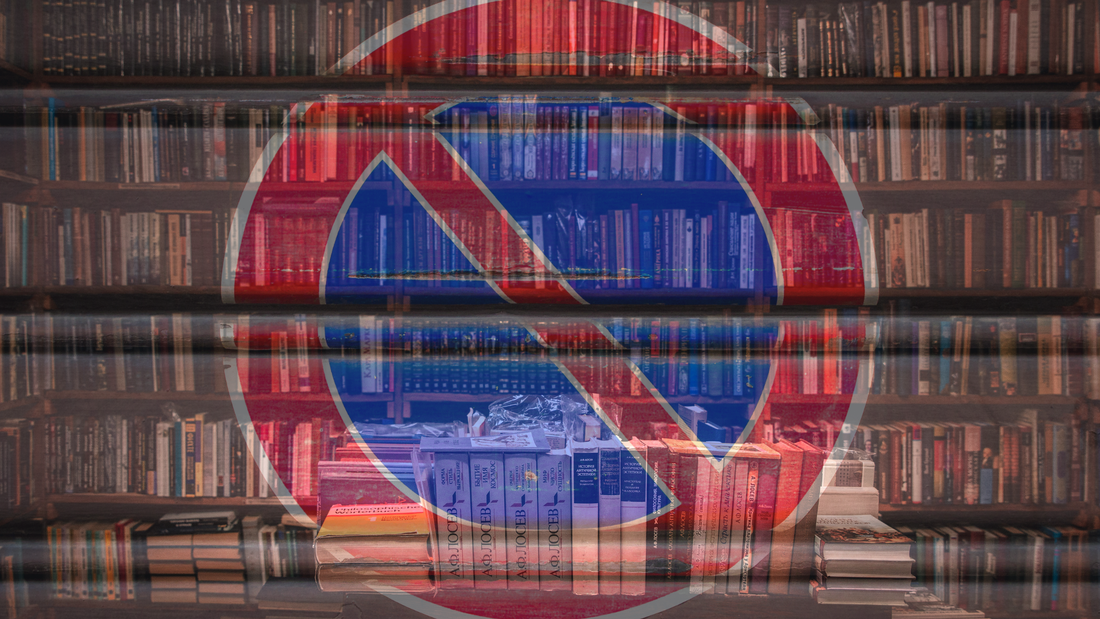

Plaintiffs before a federal court – including bookstores, libraries, and patrons of those establishments – take issue with two specific provisions in Arkansas’s Act 372. The first is Section 1, which creates misdemeanor criminal liability for librarians and booksellers, and even parents, who “[furnish] a harmful item to a minor.” The second is Section 5, which creates a process by which any citizen can challenge the appropriateness of any book in a state library according to local community standards, with final decision-making power in the hands of local county quorum courts or city councils. As the plaintiffs assert, Section 1 would result in either the widespread removal of books or an outright ban on young people under 18 from entering libraries or bookstores. Section 5, they argue, would allow vocal minorities to tell entire communities what they can and cannot read. In a remarkably restrained order and opinion, Judge Timothy L. Brooks found that the plaintiffs were likely to succeed on the merits of their case based on the overbreadth of Section 1 and the vagueness of Section 5. Regarding Section 1, Arkansas code defines “harmful to minors” as “any description, exhibition, presentation, or representation, in whatever form, of nudity, sexual conduct, sexual excitement, or sadomasochistic abuse” that lacks “serious literary, scientific, medical, artistic, or political value for minors” or would be deemed “inappropriate for minors” by the average adult, based on potentially restrictive local community standards. Factoring in the state’s very broad definition of “nudity,” it’s clear that Section 1 would result in the censorship of a vast swath of popular books, including many with only fleeting or insubstantial references to sexual conduct. It would certainly cover any book with even the most innocuous depiction of same-sex affection. Moreover, defense counsel candidly admitted in court that, under their interpretation of the law as written, any reading material deemed harmful for a five-year-old minor would also be deemed harmful for a 17-year-old minor, despite obvious differences between the two in maturity and comprehension of adult themes and issues. The U.S. Supreme Court addressed this issue in Virginia v. American Bookseller’s Association, Inc., suggesting that an interpretation of the term “harmful to minors” that includes speech protected for older minors would raise First Amendment concerns. Regarding Section 5, Judge Brooks agreed with the plaintiffs that the provision is likely “void for vagueness” because the term “appropriateness” is left entirely undefined. He further notes that it “would permit, if not encourage, library committees and local governmental bodies to make censorship decisions based on content or viewpoint.” It's worth pointing out that Arkansas already prohibits the provision of obscene material to minors. Accordingly, Judge Brooks asks, “[w]hat has happened in Arkansas to cause its communities to lose faith and confidence in their local librarians? What is it that prompted the General Assembly’s newfound suspicion? And why has the State found it necessary to target librarians for criminal prosecution?” It is better for legislators to focus on protecting children from real harms, instead of passing sure-to-be-voided legislation. Comments are closed.

|

Archives

June 2024

Categories

All

|

ABOUT |

ISSUES |

TAKE ACTION |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed