Fourth Circuit Protects Right of Religious Institutions to Make Faith-Based Employment Decisions5/29/2024

Generally speaking, terminating someone’s employment because of their sexual orientation is a gross violation of the law – and it should be. But that doesn’t apply in every instance, particularly when the employer is a religious institution engaged in guiding the spiritual development of others according to the tenets of their faith.

Lonnie Billard served as a teacher of English and drama at Charlotte Catholic High School (CCHS). After CCHS fired him for planning to marry his same-sex partner, Billard brought suit for sex discrimination under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act. The district court granted Billard’s motion for summary judgment, rejecting the school’s argument that religious exceptions inoculated them against Billard’s claim. Now, the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals has weighed in, reversing the district court’s decision, and entering judgment for the school. This is a tricky and emotional situation, and one would be forgiven for an impassioned reaction – no matter which side of the issue you’re on. Yet, from both a policy and practicality standpoint, you cannot be a teacher charged with imparting a given set of spiritual values while acting in public violation of them. Religious institutions must be able to restrict their staff positions – particularly teaching positions – to those who hold their same beliefs. Otherwise, religion would cease to mean much at all. A Methodist could teach at a mosque, an atheist at a Baptist church school, or an evangelical Christian at a high school atheist club. CCHS describes itself as “an educational community centered in the Roman Catholic faith that teaches individuals to serve as Christians in our changing world.” It posits that “individuals should model and integrate the teachings of Jesus in all areas of conduct in order to nurture faith and inspire action,” and that “prayer, worship and reflection are essential elements which foster spiritual and moral development of [CCHS’s] students, faculty and staff.” Indeed, all members of the teaching staff are expected to play a part in promoting the Christian faith. This includes leading prayers, attending Mass, and ensuring the “catholicity” of their classrooms. As such, the Fourth Circuit found that CCHS’ employment decision fell under a “ministerial exception” to Title VII. We think a better term today is a “religious mission exception,” one that covers all the positions in which those who work in a particular faith are expected to model it for others. As the Court wrote, “settled doctrine tailored to facts like these – the ministerial exception – already immunizes CCHS’s decision to fire Billard.” Drawing from the Supreme Court’s 2020 ruling in Our Lady of Guadalupe Sch. v. Morrissey-Berru, the Fourth Circuit concluded that CCHS tasked Billard with “vital religious duties,” effectively making him a “messenger” of the faith. Thus, related employment decisions require the courts to stay out. The CCHS/Billard controversy is not an ideal situation for anyone, and an employer’s similar actions in nearly any other scenario would constitute illegal discrimination. The long-established ministerial exception, however, requires the courts to abstain from weighing in on ecclesiastical employment matters – and for good reason: the First Amendment requires it, and it protects the beliefs of everyone. William Schuck writing in a letter-to-the-editor in The Wall Street Journal:

“The world won’t end if Section 230 sunsets, but it’s better to fix it. Any of the following can be done with respect to First Amendment-protected speech, conduct and association: Require moderation to be transparent, fair (viewpoint and source neutral), consistent, and appealable; prohibit censorship and authorize a right of private action for violations; end immunity for censorship and let the legal system work out liability. “In any case, continue immunity for moderation of other activities (defamation, incitement to violence, obscenity, criminality, etc.), and give consumers better ways to screen out information they don’t want. Uphold free speech rather than the prejudices of weak minds.” The just-completed Memorial Day celebration, for Virginians at least, highlighted two of our most sacred American traditions: honoring our fallen soldiers and celebrating our religious freedom.

In an unequivocal victory for the First Amendment, the National Park Service backtracked and allowed the Knights of Columbus to conduct their annual Memorial Day Mass at the Poplar Grove National Cemetery in Petersburg, Virginia. The change in course followed NPS’s denial of a permit for the Catholic fraternal organization (for the second year in a row), a decision which it based on a 2022 policy memorandum restricting the types of events that may be held within national cemeteries. The Knights of Columbus have celebrated a Memorial Day Mass at Poplar Grove since the 1960s. After learning that their permit request was again denied, the group filed for an injunction in coordination with the First Liberty Institute and the McGuireWoods law firm. In their brief, the Knights explain that NPS decided to interpret their religious service as a “demonstration,” and thus impermissible under current regulations. They write: “By prohibiting the Knights from exercising their religious convictions and expressing their patriotism by praying for and honoring the fallen through a Catholic mass held inside the cemetery, NPS is misapplying its own regulations, unlawfully infringing on the Knights’ First Amendment rights and violating the Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA).” That this blatant constitutional disregard occurred in Virginia – arguably the birthplace of America’s tradition of religious freedom (see Jefferson’s Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom, passed in 1786) – makes it all the more surprising. Some credit might be afforded to the Biden Administration for reversing course here (though the denial never should have happened in the first place). More importantly, our gratitude goes out to the Knights of Columbus for standing up for the First Amendment – and proving in the process that we don’t have to accept a shrinking space for religious liberty. These are, after all, freedoms that Americans have fought for and died to protect. A school voucher program in Pennsylvania, previously vetoed by Gov. Josh Shapiro, is getting a second chance.

The Senate Education Committee has advanced the PASS scholarship, setting it up for budget negotiations. Last year, Shapiro expressed support for the scholarships but vetoed them when faced with opposition from his fellow Democrats in the Pennsylvania House. These scholarships would provide low-income students in underperforming public schools with funds to attend private schools. The money could also cover school-related fees and special education services. Shapiro's veto message last year hinted at the possibility of reviving the scholarships, a sentiment he reiterated in his recent budget address. The current challenge remains the Democratic-majority House, influenced heavily by teachers' unions opposed to the program. The Senate leadership's firm stance and Shapiro's potential influence could lead to a different outcome this time. Public support for the scholarships is significant. A poll by the Commonwealth Foundation in March found 77 percent of registered voters in favor, including 94 percent of Black voters and 83 percent of those with incomes below $40,000. This support underscores the demand for alternatives to struggling public schools, especially in places like Philadelphia, where proficiency in basic subjects is alarmingly low. The PASS scholarship program aims to provide up to $10,000 for students in the lowest-performing districts to attend private schools. Unlike other voucher programs, it wouldn't divert funds from public schools. Yet public school advocates argue that funds should focus on improving the public education system. The debate over the school voucher program is set to intensify during the 2025 budget negotiations between the Republican-controlled Senate and the Democratic-controlled House. The outcome could significantly impact educational opportunities for many low-income students in Pennsylvania. If you live in Pennsylvania, Protect The 1st urges you to weigh in with your state representative and state senator. The U.S. House of Representatives recently passed the Antisemitism Awareness Act, a well-intentioned response to a genuine concern: escalating antisemitism, particularly on college campuses. While the motives behind this bill are commendable, the legislation, as it stands, threatens to infringe upon the free speech rights that are fundamental to American values and academic freedom. We recommend a more nuanced approach. We urge the Senate to refine the bill to effectively combat hateful conduct without compromising constitutionally protected speech – even if that speech is occasionally heinous.

The Antisemitism Awareness Act seeks to update the definition of antisemitism used in enforcing federal anti-discrimination laws, employing the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance's (IHRA) definition. This definition includes criteria such as “denying the Jewish people their right to self-determination” and “drawing comparisons of contemporary Israeli policy to that of the Nazis.” While these examples identify antisemitic speech and attitudes, their inclusion in legal statutes brings the government squarely into the business of policing and outlawing speech. This act in its current form has the potential to suppress First Amendment-protected speech. The IHRA definition, though useful as a guideline and for private criticism of antisemitic speech, is too expansive for legal application without risking the suppression of protected political expression. Legal scholars and civil rights activists have noted the dangers of such overreach, which could chill discussions on Israel and Palestine, particularly within academic institutions where vigorous debates are necessary. Worse, the act's broad language risks transforming universities into environments in which administrative caution stifles debate and discussion out of fear of legal repercussions. This could have a chilling effect on academic freedom on many subjects, as educators may become reluctant to address or discuss hot topics. From here, what effectively would be the legal suppression of speech would inevitably spread to protect other groups. A private university has the free-association right to fire a professor or suspend a student for intemperate speech. Frankly, there have been some high-profile examples of academics – glorifying the abduction and rape of women and the murder of babies on Oct. 7 – who richly deserve to spend the rest of their academic careers lecturing squirrels in the park. But the broader legal consequences of this bill in all universities for academic inquiry and the free exchange of ideas – cornerstones of higher education in the United States – are profoundly concerning. The Senate should carefully scrutinize this legislation. It is essential that any law aimed at curbing antisemitism be precise enough to target hateful behavior without punishing speech. Senators should consider amendments that clearly distinguish between hateful acts that single out people by religion and speech, no matter how intemperate, ensuring that the legislation protects individuals without compromising the robust civil discourse essential to a free society. While calling out antisemites is vital and necessary, it must not come at the expense of the constitutional rights that define American democracy and academic freedom that defines the university. We urge an approach in the Senate that robustly defends both Jewish students and free speech. And we politely suggest to supporters of the House bill that once you start to police speech, don’t be too surprised when the speech police come for you. Following conspicuous leaks of taxpayer information by the IRS and donor information by the New York attorney general’s office, a new Senate bill sponsored by Sens. Todd Young and James Lankford would increase penalties for unauthorized donor disclosure from $5,000 up to $250,000.

“In recent years, donor privacy has been threatened on too many occasions,” Sen. Young said. “This legislation will address the disclosure of donor data to better protect both charitable organizations and their donors.” But is such legislation needed? Our answer is “yes.” Challenges to donor privacy threaten a bedrock First Amendment principle in place since 1958. In that year, the U.S. Supreme Court held that the State of Alabama’s efforts to subpoena the NAACP’s membership records would threaten donors who only wanted to exercise their constitutional right to free association. Fast forward to 2021, when the U.S. Supreme Court struck down a California requirement for compelling donor disclosure for nonprofits. In the majority opinion, Chief Justice Roberts emphasized the entrenched constitutional interest in donor privacy, noting “it is hardly a novel perception that compelled disclosure of affiliation with groups engaged in advocacy may constitute as effective a restraint on freedom of association as [other] forms of governmental action.” That ruling hasn’t dissuaded some states. Arizona in 2022 passed Proposition 211, the “Voters Right to Know Act.” That measure was marketed as requiring disclosure of political “campaign” donors. Instead, it targets any group that speaks out on public policy issues – including nonprofits. It opens the door not just to self-censorship by those who may otherwise be inclined to donate to a cause, but also the possibility of doxing – using online resources for physical, emotional, or financial intimidation, harassment, and cancellation. Donor disclosure has lately been cast as a left-leaning cause – particularly in the wake of Citizens United. In reality, both sides of the aisle are getting in on the action. In the House, two separate GOP-sponsored bills would require donor disclosure by tax-exempt, non-profits in the event they receive donations from foreign nationals. One such bill, introduced by Rep. Nicole Malliotakis (R-NY), would prohibit non-profits that receive foreign donations from donating to a political campaign for eight years. We agree in principle that there is a compelling public interest in non-profits disclosing whether they receive foreign contributions. But naming individual contributors can lead to a host of constitutional concerns – not to mention the possibility of doxing and personal attacks. Not long ago, Mozilla CEO Brendan Eich was forced out of his job when the California Attorney General mandated the disclosure of donors in support of Proposition 8, which supported traditional marriage. Small donors received death threats and envelopes containing white powder. Their names and ZIP codes were helpfully overlaid on a Google Map. Exposure of donor information can also heighten donors’ fears that they, or their businesses, will be singled out by vengeful regulators with political motivations or by activist boycotts. While disclosure efforts are typically couched in the language of protecting democracy, they inevitably empower political trolls to chill speech, suppress disagreement, and organize mobs to punish those they don’t like. The Senate bill takes a thoughtful approach. Officials who leak protected donor information should face legal consequences. And perhaps non-profits should disclose whether they receive foreign contributions, as House bills seek to achieve. Anything more onerous risks the well-established constitutional rights of Americans to, in the words of Justice John Marshall Harlan II, “pursue their lawful private interests privately and to associate freely with others.” Protect The 1st is proud to announce our filing of an amicus brief before the U.S. Supreme Court in a pivotal case challenging a law in Michigan that restricts the religious rights of parents.

This legal challenge opposes what is known as a Blaine Amendment. This lawsuit is spearheaded by a group of Michigan parents confronting the amendment's prohibition on state aid to private, religiously affiliated schools. They show that it violates the Equal Protection Clause by denying families the opportunity to advocate for the freedom to choose educational options that align with their religious values. The origins of Blaine Amendments are steeped in ugly history marked by discrimination and bigotry. Initially proposed as a federal law in 1875 by House Speaker James G. Blaine, these amendments seek to prevent direct government aid to religiously affiliated educational institutions. They reflect a period of intense anti-Catholic sentiment, targeting the influx of Catholic immigrants and their schools. While the federal amendment failed, many states, including Michigan, adopted similar provisions. Michigan's Blaine Amendment, like those of other states, effectively bars state support for religious schools, impacting those who seek education aligned with their religious beliefs and cultural values. Protect The 1st believes that such amendments are not only a relic of a prejudiced past but continue to infringe on our First Amendment rights today. They undermine the pluralism that is vital to our nation’s educational landscape by restricting access to diverse schooling options that reflect familial and cultural values. This approach runs counter to the essence of American liberty and the pursuit of happiness, which includes the right of parents to direct their children's education. Our brief celebrates the opportunity to challenge Michigan’s outdated and discriminatory Blaine Amendment. By standing with the petitioners, we aim to affirm the importance of educational choice and religious freedom, ensuring that all families have the right to educate their children in a manner consistent with their beliefs. Just five days after the petitioners filed before the U.S. Supreme Court, the Court called for a response in this case, a positive sign that the Court is seriously considering granting it cert. Protect The 1st looks forward to further developments in this case. Facebook’s independent oversight board is now considering whether to recommend labeling the phrase “from the river to the sea” as hate speech. The slogan – often considered antisemitic – serves as a pro-Palestine rallying cry that calls for the creation of a unified Palestinian state throughout what is currently Israeli territory. What would happen to the millions of people who live in Israel today is, post Oct. 7th, the crux of the controversy.

However one feels about that phrase and its prominent, often uninformed, use by courageous keyboard warriors, it is appropriate that any debate about censoring it takes place in the open. This is particularly important for what is still a central social media platform, Facebook. Like X/Twitter, Instagram, and a few other media platforms, Facebook is an important venue for robust public debate. And while these private companies have every First Amendment right to moderate speech on their platforms on their own terms, because of their size and centrality we believe they nonetheless ought to be as open as possible about how they approach content moderation. Like all prominent thought leaders – individuals and companies alike – they can play an important role in reinforcing societal norms on matters of free expression, even if not legally obliged to do so. Still, at the end of the day, it’s their call. And make a call they did. According to the company, Meta analyzed numerous instances of posts using the phrase “from the river to the sea,” finding that they did not violate its policies against “Violence and Incitement,” “Hate Speech” or “Dangerous Organizations and Individuals.” This in contrast with the U.S. House of Representatives, which recently passed a resolution last month, 377-1, condemning the slogan as antisemitic. The House has a right to pass resolutions. But the opinions and sentiments of the government should not inform, and constitutionally cannot control, what we see on our news feeds. Already, we see too many instances of federal influence over social media platforms’ internal decisions, apparently done behind the scenes and always backed by an implied and sometimes expressed threat of coercion for highly regulated tech companies. Such government “censorship by surrogate” is inappropriate and inconsistent with the First Amendment. That’s why Protect the 1st opposes laws in Florida and Texas that would regulate how social media platforms police their own content. It’s simply not the place of government to use its power and influence to pressure private companies to remove posts or tell them how to make editorial choices. In this same spirit, we urge any decisions by Facebook to remove content to be done with full transparency, especially when that content is of a political nature. No law requires this, nor should it, but transparency is a sensible approach that provides clarity to consumers and reformers about societal norms regarding free expression and association. Hats off to Meta for allowing its advisory board to review and to potentially overrule its decision. Loffman v. California Department of EducationChaya and Yoni Loffman in RealClearPolicy:

“When we learned that our three-year-old son had autism, we knew that finding the right school would be hard. But we were confident that with the right help and resources, our son could thrive. “Unfortunately, California politicians disagree. When public schools fail to meet the needs of students with disabilities, the federal and state funding for that student can be redirected to private schools that are better able to accommodate their disabilities. But while California lets secular private schools receive these funds, it completely excludes religious private schools, simply because they are religious.” Michael Helfand and Maury Litwack in The Hill “A group of Los Angeles Jewish parents, children and two schools were in court this week challenging a California law that explicitly bans religious schools from becoming state-certified special needs schools, all the while allowing other private schools the ability to apply for the same state-certification. “The consequences of this law have long been devastating, preventing the Jewish community from accessing the necessary funds to build and operate educational institutions that can meet the needs of its special-needs community. “But California’s unlawful exclusion has taken on greater urgency in recent months as allegations of rampant antisemitism have plagued California educational institutions from public schools to college campuses. Now, California’s rules put Jews in a damned-if-you-do, damned-if-you-don’t dilemma: You can’t have your own schools, and when you come to our schools, be prepared for an environment hostile to your Jewish identity and practices. California cannot allow this state of affairs to continue.” The latest from FIRE, the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression. During his 2020 presidential campaign, Joe Biden made a bold promise to be the most pro-union president in history. According to analysis by Tom Hebert in The Washington Times, this pledge has translated into a troubling reality. Biden has weaponized federal regulations to suppress free speech within workplaces, all to increase the strength of unions. This manipulation of regulatory power underscores a stark departure from advocating for workers' rights, veering instead towards serving union agendas at the expense of free expression.

Leading the charge in this regulatory shift is the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB). Traditionally, employers have been able to hold meetings, known as employer meetings on unionization (EMUs), to discuss unionization transparently with employees. These meetings, which have been uncontroversial since the 1940s, compensate employees for their time and educate them on their rights. The NLRB’s recent recommendation to ban EMUs marks a significant policy reversal. This move is a strategic attempt to leave workers uninformed and sway them toward union membership. This aggressive stance against EMUs has been echoed in several states, pushing to restrict these meetings despite their longstanding acceptance and the fair context in which they were traditionally held. A specific example of the NLRB's controversial approach involves Amazon CEO Andy Jassy, who faced allegations of labor law violations based on paraphrased comments from public interviews, rather than direct quotes. Jassy discussed the benefits of non-unionized workplaces, specifically noting their agility in making improvements without the bureaucratic hurdles posed by unions. However, these comments were interpreted by the NLRB as threats to workers, lacking objective evidence and direct quotes. This method of interpretation demonstrates how regulatory bodies might stretch interpretations to silence employer perspectives during union drives. Legislative initiatives like the Protecting the Right to Organize (PRO) Act underscore a growing disregard for free speech in the workplace. As Hebert says, “one little-known PRO Act provision would force employers to hand over sensitive employee contact information – including phone numbers, email addresses, home addresses and shift times – to union bosses during organizing drives. If the act became legal, workers on the fence about unionization could get a 3 a.m. knock on the door from organizers attempting to “help them make up their minds.” This provision effectively silences any counter-narrative to unionization at a critical decision-making moment, highlighting a troubling shift toward limiting open dialogue and enhancing union influence under the guise of worker protection. The ongoing crackdown on free speech in the workplace not only threatens the foundational rights of employees and employers but also reflects a larger governance trend where union interests are prioritized over open dialogue and workers' rights. The challenge lies in balancing these interests without undermining the principles of workplace democracy and freedom of expression, ensuring that all voices can be heard and respected in the critical conversations about unionization. Protect The 1st emphasizes the importance of free and open discourse in any decision-making process about unions. We look forward to further developments in this story. Iowa has proudly become the 27th state to enact its own version of the Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA), reinforcing the Hawkeye State’s commitment to the right of religious expression. This landmark legislation underscores Iowa's alignment with a majority of states that have already recognized the importance of protecting religious freedoms at the state level. By adopting RFRA, Iowa joins a diverse coalition of states – from Massachusetts to Texas – committed to safeguarding the freedoms that form the cornerstone of American values.

RFRA is designed to ensure that any government action potentially infringing on religious practices serves a compelling governmental interest in the least restrictive manner possible. Iowa’s RFRA reflects the Hawkeye State’s deep respect for individual rights and religious diversity. This law isn't merely a replication of the federal RFRA passed thirty years ago, but a reaffirmation of a commitment seen across a spectrum of states, both red and blue. The original federal law, championed by political figures such as Chuck Schumer and Ted Kennedy and signed by President Bill Clinton, showcases the bipartisan foundation upon which the RFRA stands. Such historical bipartisanship highlights the act's fundamental purpose: protecting religious freedoms. While concerns have been raised about potential misuses of the RFRA, particularly regarding discrimination against LGBTQ individuals, states with longstanding RFRAs like Connecticut and Illinois have been recognized as among the best for LGBTQ rights. These examples demonstrate that RFRAs can coexist with strong protections for minority communities. The Becket Foundation reminds us that RFRAs have historically defended the rights of various minority groups – from Native Americans to Muslims and Sikhs – against governmental overreach without negating anti-discrimination laws concerning race or gender. Religious freedom is no zero-sum game. The adoption of RFRA in Iowa also coincides with a national shift towards more robust protections of individual rights, as seen in the prairie fire expansion of school choice from coast-to-coast. This trend reflects a growing recognition of the importance of safeguarding personal freedoms against governmental overreach. More states should take Iowa’s example to heart. Respecting deeply held religious beliefs and protecting civil rights are not mutually exclusive objectives. The continued expansion of RFRA laws could serve as a model for maintaining harmony between personal liberties and social obligations, ensuring that religious freedom remains a protected and cherished American value. Protect The 1st congratulates Gov. Kim Reynolds on her accomplishment and urges every state to join the push to protect religious freedom. Sometimes it seems as if the left and the right are in a contest to see which side can be the most illiberal. With each polarity defining the other as a “threat to democracy,” restrictions on political opponents are rationalized away as a necessary act of public hygiene. Recent events in Europe, from Budapest to Brussels, should serve as a warning to Americans who want to use police power to make their opponents shut up.

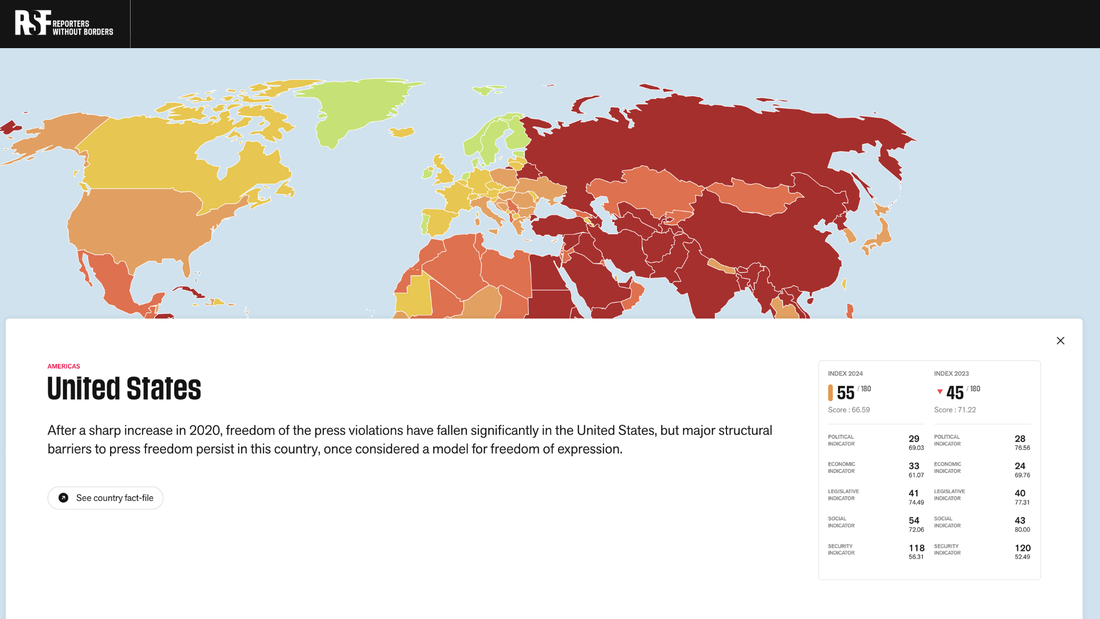

In December, the U.S. State Department warned that a new Sovereign Defense Authority law in Hungary “can be used to intimidate and punish” Hungarians who disagree with Prime Minister Viktor Orbán and his ruling party. No less an observer than David Pressman, the U.S. ambassador in Budapest, said: “This new state body has unfettered powers to interrogate Hungarians, demand their private documents and utilize the services of Hungary’s intelligence apparatus – all without any judicial oversight or judicial recourse for its targets.” So how are left-leaning critics responding to the rise of the Europe right? By also using intimidation to shut down speech. In Brussels, police in April acted on orders from local authorities by forcibly shutting down a National Conservatism conference. This event, which was to host discussions among European conservative figures, including Prime Minister Orbán and former Brexit champion Nigel Farage, was terminated hours after it began. The cited reasons for the closure included concerns over potential public disorder linked to planned protests. Such a policy, of course, gives protesters pre-emptive veto power over controversial speech, backed by the police. The conference had earlier faced official meddling to prevent the selection of a venue. Initial plans to host the event at the Concert Noble were thwarted due to pressure from the Socialist mayor of Brussels. Subsequently, a booking at the Sofitel hotel in Etterbeek was canceled after local activists alerted that city’s mayor, who pressured the hotel to withdraw its support. Finally, the organizers settled on the Claridge Hotel, only to encounter further challenges including threats to the venue’s owner and logistical disruptions orchestrated by local authorities, culminating in the police blockade that effectively stifled the conference. The good news is public response to the shutdown of the National Conservatism conference was vocal and critical. Belgian Prime Minister Alexander De Croo voiced a strong objection, stating that such bans on political meetings were unequivocally unconstitutional. British Prime Minister Rishi Sunak also responded that canceling events and de-platforming speakers is damaging to democracy. The closure in Brussels is particularly ironic given the city's status as the capital of the European Union, a supposed bastion of liberal democratic values. The forced closure, threats to cut electricity, and the barring of speakers are tactics that betray a fundamental disrespect for democratic norms. What transpired was a scenario more befitting a "tinpot dictatorship," as Frank Füredi, one of the event's organizers, put it. Speech crackdowns seem to be a European disease. This aggressive move to silence a peaceful assembly under the guise of preventing disorder echoes the same illiberal impulses driving Scotland's Hate Crime and Public Order Act. That law broadly criminalizes speech under the expansive banner of “stirring up hatred.” Americans would do well to look to Europe to see what cancellation and criminalization of speech looks like. As the cities and campuses of the United States face what promises to be a hot summer of protest over Gaza, Americans need to keep a relentless focus on protecting speech – even speech one regards as heinous – while preventing tent city invasions, vandalism, and violence that compromises the rights of others. Reporters Without Borders dropped the United States 10 places on its annual rankings from last year, from 45th to 55th place out of 180 countries in its 2024 World Press Freedom Index. This is part of a trend. This NGO has downgraded the United States, which enshrines freedom of the press in our Constitution, from 17th best for press freedom in 2002 to that 55th place now.

To be fair, some of the organization’s metrics are questionable. For example, Argentina fell from 40th place last year to 66th place in 2024 after newly elected President Javier Miliei shuttered news outlet Télam and put its 700 journalists on the street. It should be noted, however, that Télam was a money-losing, state-funded news agency founded by Juan Perón and known for being a government and Peronista mouthpiece under previous administrations. So how fairly did Reporters Without Borders treat the United States? It seems overkill to us to rank the United States below the Ivory Coast, where reporters are routinely called in by prosecutors and newspapers are suspended – or Romania, where a prominent journalist who investigated the government had her personal images hacked and uploaded to an adult website. At the same time, while we can take issue with the overall ranking of the United States, this NGO is correct on what the British call the direction of travel. Protect The 1st has reported what Reporters Without Borders states: “In several high-profile instances, local law enforcement has carried out chilling actions, including raiding newsrooms and arresting journalists.” We would add to that the lack of a federal press shield law also leaves reporters vulnerable to being wiretapped and worse. The good news is that protections for reporters have a strong basis of public support in the United States. A recent survey by the Pew Research Center reveals robust support among Americans for the principle of press freedom, underscoring its vital role in our democracy. It’s heartening to note that nearly three-quarters of U.S. adults (73 percent) consider the freedom of the press — enshrined in the First Amendment — extremely or very important to the well-being of society. Still, we have reason for caution. While a significant majority of Americans acknowledge the importance of a free press, many are concerned about threats to journalistic freedom. Notably, a substantial portion of the population believes U.S. media is influenced by corporate and political interests — 84 percent and 83 percent respectively. In our polarized society, partisan differences color these perceptions of press freedom. Republicans and Independents consistently express greater concern over media restrictions and the influence of political interests compared to Democrats. Equally concerning is the broader debate over the balance between safeguarding press freedom and curbing “misinformation.” Approximately half of the American population is torn between the necessity to prevent the spread of false information and the imperative to protect press freedoms, even if it means some false information might circulate. While it's encouraging to see strong support for journalistic freedoms among Americans, local authorities must understand that raids and legal threats against reporters is intolerable under our Constitution and under the press shield laws of 49 states. And we need a federal press shield law – the PRESS Act, which recently passed the U.S. House – to reduce the shadow the Department of Justice can cast over the free exercise of journalism. We’ve got work to do. Congress Should Celebrate It by Passing the PRESS ActLike many declarations of the United Nations, the 31st anniversary of World Press Freedom Day is more aspirational than reality in many UN member countries.

In some countries, journalists are routinely killed for reporting on corrupt politicians and police agencies. UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres’ says that violence is also common among journalists covering local environmental issues like illegal mining, logging, poaching and other acts of “environmental vandalism.” Much of the repression comes from sophisticated state actors. In China, imprisoned Hong Kong publisher Jimmy Lai stayed in that jurisdiction to bravely stare down official repression after his newspaper, Apple Daily, was shuttered. In Russia, Evan Gershkovich of The Wall Street Journal remains held on specious charges of spying for the CIA by Vladimir Putin’s judicial puppets. “Journalism should not be a crime anywhere on the earth,” President Biden declared today. We agree and would only add, for unfortunately necessary emphasis, “including the United States.” While 49 U.S. states have press shield laws, there is no federal law that protects the notes and sources of a journalist from being seized by a federal prosecutor. Many U.S. reporters have gone to jail rather than bow to a prosecutor’s demand to reveal his or her sources. All the more reason to celebrate World Press Freedom in America by asking Congress to get behind the PRESS Act, which would extend these basic protections to the federal government. “If you cannot offer a source a promise of confidentiality as a journalist, your toolbox is empty,” celebrated investigative journalist Catherine Herridge told members of a House Judiciary subcommittee. “No whistleblower is coming forward, no government official with evidence of misconduct or corruption. And what that means is that it interrupts the free flow of information to the public … Journalism is about an informed electorate, which is the bedrock of our democracy.” We urge Congress to honor the First Amendment and the freedom of the press by passing the PRESS Act. Where to Draw the Line on Speech? As student pro-Palestine protests evolved into harassment and shut-downs of the University of Southern California and Columbia University campuses, the University of Texas was presented with a Gordian knot of free-speech issues. When University of Texas protesters planned a march through campus, administrators said they had intelligence that non-student activists were planning on leading students to occupy the campus with a tent city (sleeping on the campus lawn is against university rules). This could have shut down the university.

With the backing of Gov. Gregg Abbott, police chose to simply cut the knot by arresting 57 peaceful protesters on campus. That event leaves us with hard questions about the limits and protections of speech rights within the academy. In late March, Texas Gov. Greg Abbott ordered public universities to revise their free speech policies, specifically targeting antisemitic rhetoric. The governor’s response is understandable after lax concern shown by the former presidents of Harvard and other institutions about on-campus antisemitism. But viewpoint-based bans on rhetoric rather than behavior had the practical effect of targeting pro-Palestine student groups, which are often wellsprings of intemperate speech. The governor’s executive order put the University of Texas in an awkward position. The First Amendment applies specifically to the federal government, and the states via the Fourteenth Amendment. Courts have held freedom of speech and assembly to apply to public universities as well. Under both the U.S. and Texas Constitutions, the University of Texas cannot unduly restrict these rights. While the law allows for “reasonable time, place, and manner” restrictions to ensure public safety and order, these must be neutrally applied, without viewpoint discrimination. Despite this, many of the recent arrests of the protesters at the University of Texas were arguably necessary, given the warnings on which they were based. Columbia University demonstrated that laxity about existing time, place, and manner restrictions led to students living in tents, shutting down live instruction, and violently taking over a building. Columbia finally demanded students leave or face suspension. Some who broke into and occupied an academic building will likely face expulsion. At USC, potentially violent protests have shut down that school’s commencement. In light of events at other universities, it is easy to see the UT administrators’ dilemma. Should they have stood by to see if their intelligence regarding planned disruptions was correct, acting only if the worst came to pass? This might have led to the same worst-of-both-worlds scenario we saw at Columbia, where classrooms and open discourse were shut down and the school still had to rely on police to clear out the occupiers. At such a point, how many cracked skulls would it have taken to clear the University of Texas? For their part, students, faculty, and advocacy groups argue that the arrests of peaceful protesters who announced their march in advance was disproportionate. They also point to a 2019 Texas state law that designates common outdoor areas on public university campuses as traditional public forums. Supported by Gov. Abbott and conservative lawmakers, this law protects broad expressive activities, provided they do not disrupt campus functions or break the law. But before we cue the petards to be hoisted, consider that a planned occupation would definitely have disrupted instruction and broken the law. But did their evidence of a planned occupation meet the standard of a “clear and present danger? This tension at the University of Texas reflects the larger national debate about the complex nature of speech rights, especially in academic settings where the free and open exchange of ideas is to be encouraged, not quelled. There is a legitimate need to maintain order and safety on campus. There is also a constitutional imperative to protect free speech, including speech many find offensive. Gov. Abbott’s crackdown on campus antisemitism reflected commendable concern. But hate speech laws are notoriously overbroad and often unworkable. “True threats” are a legitimate (and necessary) reason for authorities to intervene. Most likely, fighting words and incitement to violence likewise can be restricted and punished. But some latitude is needed for more ambiguous chants like “from the river to the sea” – the plain meaning of which is the violent abolition of Israel but could be taken by a student as merely a call for freedom or a criticism of “colonialism.” Never mind how doubtful you may find that interpretation or blinkered you may find that tired trope. The First Amendment protects all speech, including stupid speech. Thus, any intrusion into speech rights that Abbott permits today could enable further restrictions down the line (and restrict in directions the governor may not like). Misunderstandings about the First Amendment are at the core of such dilemmas. It is odd that elite private universities, Columbia, Yale, and USC, which have more latitude in enforcing discipline, stood by in stupefied inaction at the harassment of Jewish students and disruption of classroom learning. One protester at Yale stabbed a Jewish student in the eye with a Palestinian flag. True threats and fighting words have a way of becoming acts of violence, which is why Columbia finally did bar a student who said “Zionists don’t deserve to live.” Universities, public and private, must never forget the imperative that universities remain centers of free inquiry and discussion, reflecting the constitutional rights and values they are built to impart. They must also protect their students and classrooms. Like all dilemmas, this one at least contains teachable moments. Where better to teach these intricacies of the First Amendment? Can a protest organizer be held civilly liable for the unlawful actions of another at a demonstration? That’s the question at issue in McKesson v. Doe, one with significant implications for protected speech.

The case’s circuitous journey through the courts started in 2016, when an anonymous Louisiana law enforcement officer was struck with a “rock-like” object hurled by an unknown person at a Black Lives Matter protest. This was a despicable act of violence that was in no sense expressive speech. Those who commit such acts of violence must be prosecuted to the fullest extent of the law. But what is the liability of those who organize a peaceful protest that is infiltrated by the violent? Plaintiff John Doe brought suit against activist DeRay McKesson, who organized the event, on the theory that McKesson’s role as the event organizer encompassed a duty to protect everyone present. In 2020, the U.S. Supreme Court vacated the Fifth Circuit’s decision against McKesson, which upheld a novel theory from Doe of “negligent protest.” The Court remanded the case to the Louisiana Supreme Court, instructing it to analyze whether state law actually provides for negligence liability in such situations. This decision seems to ignore precedent in NAACP v. Claiborne Hardware, which held that “[c]ivil liability may not be imposed merely because an individual belonged to a group, some members of which committed acts of violence.” The Louisiana Supreme Court ultimately reached the conclusion that state tort law does, in fact, provide Doe with a cause of action. As a result, the Fifth Circuit reinstated its ruling and the case returned again to the highest court in the land. Notably, the Supreme Court ruled in the intervening years in Counterman v. Colorado that a subjective, mens rea standard (meaning specific intent, not just negligence) is required for a finding of liability in lawsuits that seek to punish speech. Justice Kagan wrote that the “First Amendment precludes punishment, whether civil or criminal, unless the speaker’s words were ‘intended’ (not just likely) to produce imminent disorder.” Accordingly, in an order rejecting certiorari in the McKesson case earlier this month, Justice Sotomayor strongly implied that the Court has already settled this question of law. She wrote, “Although the Fifth Circuit did not have the benefit of this Court’s recent decision in Counterman when it issued its opinion, the lower courts now do. I expect them to give full and fair consideration to arguments regarding Counterman’s impact in any future proceedings in this case.” The Supreme Court clearly wants to allow some deference to state law. However, it seems entirely reasonable to require a showing of intent in situations involving the random outbreak of violence at protests. Failure to do so could have a significant, chilling effect on political speech. If civil liability can be assigned for merely organizing an event, then we’re likely to see a lot less civil discourse in the future. Journalists have similar concerns. As the Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press explains, protecting against liability for the “uncoordinated,” lawless actions of others “is a critical safeguard for reporters who attend tumultuous events where violence may break out — political rallies, say, or mass demonstrations — in order to bring the public the news.” It remains possible the Fifth Circuit may reevaluate its ruing in light of Counterman, but it’s disappointing that the Supreme Court declined to weigh-in in a meaningful way. When states start imposing low liability thresholds on protestors, it jeopardizes First Amendment protections for all of us. Former U.S. Representatives, Bob Goodlatte (and our senior policy advisor) and Barbara Comstock, provide insight in The Hill about the latest House hearing highlighting the latest threat to journalism and why the Senate should finally pass the PRESS Act.

Can a government regulator threaten adverse consequences for banks or financial services firms that do business with a controversial advocacy group like the National Rifle Association? Can FBI agents privately jawbone social media platforms to encourage the removal of a post the government regards as “disinformation”?

As the U.S. Supreme Court considers these questions in NRA v. Vullo and Murthy v. Missouri, a FedSoc Film explores the boundary between a government that informs and one that uses public resources for propaganda or to coerce private speech. (“Nice social media company you have there. Shame if anything happened to it.”) Posted next to this film, Jawboned, on the Federalist Society website is Protect The 1st’s own Erik Jaffe, who in a podcast explores the extent to which the government, using public monies and resources, should be allowed to speak, if at all, on matters of opinion. Is the expenditure of tax dollars to push a favored government viewpoint a violation of the First Amendment rights of Americans who disagree with that view? Jaffe thinks so and argues why this is the logical conclusion of decades of First Amendment jurisprudence. Furthermore, when the government tells a private entity subject to its power or control what the government thinks it ought to be saying (or not saying), Jaffe says, “there’s always an implied ‘or else.’” And even the government’s own public speech often has coercive consequences. As if to underscore this point, Jawboned recounts the story of how the federal Office of Price Administration during World War Two lacked the authority to order companies to reduce prices but did threaten to publicly label them and their executives as “unpatriotic.” That was a very real threat in wartime. Imagine the “or else” sway government has today over highly regulated firms like X, Meta, or Google. In short, Jaffe argues that a line is crossed when “the power and authority of the government” is invoked to use “the power of office to coerce people.” But it also crosses the line when the government uses its resources (funded by compelled taxes and other fees) to amplify its own viewpoint on questions being debated by the public. Such compelled support for viewpoint selective speech violates the freedom of speech of the public in the same way compelled support for private expressive groups and viewpoints does. Click here to listen to more of Erik Jaffe’s thoughts on the limits of government speech and to watch Jawboned. Now that the bill to force the sale of TikTok has passed the U.S. Senate, and its signature by President Biden is certain, Protect The 1st as a First Amendment organization must speak out.

We believe the bill – soon-to-be-law – is reasonable. Many of our fellow civil liberties peers make the valid point that if the government can silence one social media platform, it can close any media outlet, newspaper, website, or TV channel. We would oppose any such move with forceful public protest. But this is a compelled divestiture, which seems like the least restrictive way to protect the speech rights of TikTok’s American users while protecting their data. TikTok’s content is not the issue. The issue is one of ownership and operations. The fundamental problem, of course, and the problem that gave rise to this legislation, is that TikTok is obligated by Chinese law to share all its data with the People’s Liberation Army, the military wing of the Chinese Communist Party. Under President Xi Jinping, Beijing has crushed democracy in Hong Kong, and silenced a newspaper – Apple Daily – while imprisoning its publisher, Jimmy Lai. Xi’s regime also frequently expresses malevolent intentions toward the United States. It arms Russia’s imperialist war to conquer Ukraine, a democracy. And it frequently advertises its own imperialist plan to conquer Taiwan, another democracy. It doesn’t make sense to treat a publication utterly beholden to a regime that shutters newspapers, imprisons publishers, and supports wars on democracies as if it were just another social media platform. Caution is warranted. A crisis between the United States and China is growing increasingly likely. TikTok gives China the means to dig into the private data of 150 million Americans, including families with parents working in the U.S. military, government, and business. To mandate a sale to an owner outside of China would begin the protection of Americans’ data, while allowing TikTok to remain the popular and vivid platform that people enjoy. For more background on this issue, check out this recent PT1st post. Just before folding up its presidential bid, No Labels won its court battle to block candidates from using its ballot line to run for office in Arizona. No Labels is a “centrist” political party that had been gearing up for a potential third-party presidential campaign to take on Joe Biden and Donald Trump. Despite No Labels collapse, this decision is a big win for the freedom of association – held by the U.S. Supreme Court to be the logical outcome of the First Amendment’s rights of free speech, assembly, and petition.

No Labels in October sued Adrian Fontes, the Secretary of State for Arizona, in an effort to keep potential down-ballot contenders from running as No Labels candidates without authorization. This should not have been necessary since No Labels did not plan to run congressional candidates. No Labels filed suit shortly after Richard Grayson, a man who has run for office at least 19 times, announced he would run as candidate for a minor state office under the party’s banner. Under Arizona law, this would have forced the fledgling movement to reveal its donors. Some Democrats have accused No Labels of being a spoiler that will poach votes from Biden, helping to pave the way for Trump to return to the White House. “I will use the campaign to expose the scam of No Labels (and to) excoriate the selfish and evil people who have organized this effort and their attempt to make sure that Donald Trump wins in November,” Grayson said. Courts have long recognized that for the freedom of association to mean anything we must respect its flip side – the freedom to refuse association. Both rights are subject to reasonable limitations, but such reciprocity is necessary in any relationship. Dr. Benjamin F. Chavis, Jr., a No Labels national co-chair, and former Missouri Gov. Jay Nixon, the group’s director of ballot integrity, said in a statement that, “Our ballot line cannot be hijacked. Our movement will not be stopped.” Just like Vivek Ramaswamy could not automatically declare himself Trump’s running mate, a No Labels party member should not be able to unilaterally declare himself or herself a candidate on the ballot with no input from party leaders. Federal Judge John J. Tuchi ruled that to enable Grayson to run as a No Labels candidate without prior authorization from the party would violate the party’s chosen structure and rights. “The Party has substantial First Amendment rights to structure itself, speak through a standard bearer, and allocate its resources,” Judge Tuchi wrote. Protect The 1st strongly supports Judge Tuchi’s ruling. This clear stand for association rights is a significant reaffirmation of the Constitution, regardless of any political implications. A House hearing on the protection of journalistic sources veered into startling territory last week.

As expected, celebrated investigative journalist Catherine Herridge spoke movingly about her facing potential fines of up to $800 a day and a possible lengthy jail sentence as she faces a contempt charge for refusing to reveal a source in court. Herridge said one of her children asked, “if I would go to jail, if we would lose our house, and if we would lose our family savings to protect my reporting source.” Herridge later said that CBS News’ seizure of her journalistic notes after laying her off felt like a form of “journalistic rape.” Witnesses and most members of the House Judiciary subcommittee on the Constitution and Limited Government agreed that the Senate needs to act on the recent passage of the bipartisan Protect Reporters from Exploitative State Spying (PRESS) Act. This bill would prevent federal prosecutors from forcing journalists to burn their sources, as well to bar officials from surveilling phone and email providers to find out who is talking to journalists. Sharyl Attkisson, like Herridge a former CBS News investigative reporter, brought a dose of reality to the proceeding, noting that passing the PRESS Act is just the start of what is needed to protect a free press. “Our intelligence agencies have been working hand in hand with the telecommunications firms for decades, with billions of dollars in dark contracts and secretive arrangements,” Attkisson said. “They don’t need to ask the telecommunications firms for permission to access journalists’ records, or those of Congress or regular citizens.” Attkisson recounted that 11 years ago CBS News officially announced that Attkisson’s work computer had been targeted by an unauthorized intrusion. “Subsequent forensics unearthed government-controlled IP addresses used in the intrusions, and proved that not only did the guilty parties monitor my work in real time, they also accessed my Fast and Furious files, got into the larger CBS system, planted classified documents deep in my operating system, and were able to listen in on conversations by activating Skype audio,” Attkisson said. If true, why would the federal government plant classified documents in the operating system of a news organization unless it planned to frame journalists for a crime? Attkisson went to court, but a journalist – or any citizen – has a high hill to climb to pursue an action against the federal government. Attkisson spoke of the many challenges in pursuing a lawsuit against the Department of Justice. “I’ve learned that wrongdoers in the federal government have their own shield laws that protect them from accountability,” Attkisson said. “Government officials have broad immunity from lawsuits like mine under a law that I don’t believe was intended to protect criminal acts and wrongdoing but has been twisted into that very purpose. “The forensic proof and admission of the government’s involvement isn’t enough,” she said. “The courts require the person who was spied on to somehow produce all the evidence of who did what – prior to getting discovery. But discovery is needed to get more evidence. It’s a vicious loop that ensures many plaintiffs can’t progress their case even with solid proof of the offense.” Worse, Attkisson testified that a journalist “who was spied on has to get permission from the government agencies involved in order to question the guilty agents or those with information, or to access documents. It’s like telling an assault victim that he has to somehow get the attacker’s permission in order to obtain evidence. Obviously, the attacker simply says no. So does the government.” This hearing demonstrated how important Fourth Amendment protections against unreasonable searches and seizures are to the First Amendment’s guarantee of freedom of the press. If Attkisson’s claims are true, the government explicitly violated a number of laws, not the least of which is mishandling classified documents and various cybercrimes. And it relies on specious immunities and privileges to avoid any accountability for its apparent crimes. Two proposed laws are a good way to start reining in such government misconduct. The first is the PRESS Act, which would protect journalists from being pressured by prosecutors in federal court to reveal their sources. The second proposed law is the Fourth Amendment Is Not For Sale Act, which passed the House this week. This bill would require the government to get a warrant before it can inspect our personal, digital information sold by data brokers. And, of course, these and other laws limiting government misconduct need genuine remedies and consequences for misconduct, not the mirage of remedies enfeebled by improper immunities. A group of pro-Palestine student activists recently hijacked a private dinner at the home of Erwin Chemerinsky, dean of Berkeley Law School, disrupting one of several such events intended to honor the graduating class of 2024. It’s a lesson in decorum, which these students clearly lack. More importantly, it’s a lesson that Chemerinsky himself might cover in one of his constitutional law classes or legal tomes: You have no First Amendment right to public speech on private property.

Chemerinsky himself summarized the disruption in a written statement: “On April 9, about 60 students came to our home for the dinner. All had registered in advance. All came into our backyard and were seated at tables for dinner. While guests were eating, a woman stood up with a microphone, stood on the top step in the yard, and began a speech, including about the plight of the Palestinians. My wife and I immediately approached her and asked her to stop and leave. The woman continued. When she continued, there was an attempt to take away her microphone. Repeatedly, we said to her that you are a guest in our home, please stop and leave. About 10 students were clearly with her and ultimately left as a group.” Alarmingly, the incident followed the publication and display of a poster calling for a boycott of the dinner events, with accompanying cartoon imagery depicting the dean holding a knife and fork covered with blood. The caption read: “No dinner with Zionist Chem while Gaza starves.” The link between Chemerinsky and Israel’s military campaign in Gaza is nebulous, to say the least. Chemerinsky is an American constitutional scholar, not an Israeli war planner. The only inference to be made is that the dean was targeted solely due to his Jewish heritage. For their part, the protestors (seen here in a video of the incident) asserted a First Amendment right to their interruption. To parse the legitimacy of such claims, we might turn to an actual First Amendment scholar, Eugene Volokh, who wrote about the dinner in a recent The Volokh Conspiracy post. He wrote: “Some people have argued that the party was a public law school function, and thus not just a private event. I’m not sure that’s right – but I don’t think it matters. “Even if Berkeley Law School put on a party for its students in a law school classroom, students still couldn’t try to hijack that for their own political orations. Rather, much government property is a ‘nonpublic forum’ – a place where some members of the public are invited, but which is ‘… not by tradition or designation a forum for public communication.’ (Minnesota Voters Alliance v. Mansky (2018) ...” Outside of the protestors’ erroneous legal argument, one might also consider the efficacy of their outburst. Above the Law founder David Lat contrasted the Berkeley protestors’ behavior with that of protestors at the University of Virginia, who recently turned out against a speech by Justice Jay Mitchell of the Alabama Supreme Court (author of the infamous IVF case). There, the protestors “didn’t heckle or harass Justice Mitchell, me, or anyone else who went into his talk. They stood outside the room, quietly holding signs. And once his talk got underway, they left to attend a counter-event …” How refreshing. Inasmuch as the protestors got it wrong here, Berkeley (for once) got it right. In a statement to Law 360, UC Berkeley Chancellor Carol T. Christ said: “I am appalled and deeply disturbed by what occurred at Dean Chemerinsky's home last night. I have been in touch with him to offer my support and sympathy. While our support for free speech is unwavering, we cannot condone using a social occasion at a person's private residence as a platform for protest.” UC Board of Regents Chair Rich Leib, meanwhile, said: “The individuals that targeted this event did so simply because it was hosted by a dean who is Jewish. These actions were antisemitic, threatening, and do not reflect the values of this university.” Berkeley’s reputation as the home of the Free Speech Movement (the name became somewhat Orwellian), continues a decidedly spotty record in recent years. The university’s unequivocal embrace of actual, settled First Amendment doctrine in this instance represents an encouraging development. Naturally, the protestors have since hoisted the banner of victimhood, claiming “pain, humiliation, trauma, and fear” following the incident. With time, we hope they learn the lesson that, in the words of Ronald K.L. Collins in a FIRE blog: “the First Amendment is a shield against government suppression. It is not an ax to swing at compassionate and freedom-loving people in their own homes.” Law schools might further promote First Amendment education by turning to disciplinary action for law students who refuse to learn the nuances of this central principle of American life. In the verdant, rugged landscapes of Scotland, known for its fierce independence and love of freedom, the country’s parliament has hammered another nail in the coffin of free speech. The Hate Crime and Public Order Act, intended to consolidate and expand protections against hate crimes, has sparked a heated argument about its restrictions encroaching on free expression.

The act updates existing laws, adding age and potentially sex to the list of characteristics to be protected from offensive statements. It introduces a new offense for stirring up hatred against protected groups. And while the law also abolishes blasphemy, an offense not prosecuted for more than 175 years, it effectively replaces it with the broader offense of “stirring up hatred” since many groups may view blasphemy as hatred against them. Restricting controversial speech has itself ignited controversy, reflecting a global trend in the UK, Canada, and Australia, where the bounds of legally protected speech are being redrawn. The law's reception has generated significant concern over its implications for freedom of speech throughout the English-speaking world. The act’s critics – J.K. Rowling, as well Joe Rogan and Elon Musk in America – argue that in its effort to protect, the law risks stifling open discourse on contentious subjects, such as gender and sexuality. Some of the most hotly debated issues of the day are now legally risky to discuss. J.K. Rowling directly challenged the law by publicly defying its perceived restrictions on speech concerning gender identity. Through a series of tweets that critiqued aspects of transgender activism and its impact on women's rights, Rowling provocatively dared the police to arrest her, testing the limits of the new law's application. Despite the contentious nature of her commentary, authorities concluded that her actions did not constitute a criminal offense under the act. But the next speaker to criticize the views and ideologies of protected groups may not receive so tolerant a reception from the Scottish authorities. Rowling’s situation stands in contrast to the standard of speech applied in the United States, where the Supreme Court's ruling in Brandenburg v. Ohio protects speech unless it is intended and likely to incite imminent lawless action. Under this doctrine, much of the speech potentially criminalized under Scotland's new law remains protected in the United States. In Scotland, however, even when the law isn’t enforced it will have a chilling effect. Rowling is a high-profile figure with resources both financial and social; she is not an easy target to take down. This law could still be deployed against people without 14 million Twitter followers and ample legal resources to back them up. Free speech is hard. It demands a lot of a society, and what it provides in return is more long-term and difficult to measure. One short-term consequence of misguided restrictions, however, is that they often have the opposite effect than was intended, providing the allure of the forbidden to disreputable ideas. This amplification, reminiscent of the Streisand Effect, is already on display. And because broad and vague standards like stirring up hatred can cut in many different directions, groups most likely to peddle in such vitriol will be equally quick to play the victim when they, too, are criticized. Neo-Nazi and far-right groups thus have predictably attempted to overwhelm the Scottish police with complaints under the new law claiming that criticism stirs up hatred against them. This experience alone suggests that, far from quelling hate speech, the legislation may inadvertently give it a louder voice or make it impossible to even discuss the sources and causes of real crimes. Hate crime reports in Scotland are currently on track to outpace all other crimes reported to the police this year. The necessity of free speech – as a foundational pillar of democracy and civil society – cannot be overstated. It is deeply ironic that this restrictive law has emerged from the same country that once gave rise to the Scottish Enlightenment and the ideals of liberty and limited government. Here in the United States, we long ago broke from the British Empire and rejected more restrictive views and abuses regarding speech, religion, and other important liberties. We should make sure not to follow Britain back towards a more repressive view regarding the freedom of speech, especially on matters of public controversy and debate. The debate in Scotland offers valuable lessons for democracies worldwide, reminding us of the delicate balancing act required of a society committed to free speech. As Ben Franklin once said: “They who can give up essential liberty to obtain a little temporary safety, deserve neither liberty nor safety.” Donald Trump’s hush money trial is bringing new meaning to the term “hush” following Justice Juan Merchan’s issuance of a gag order to protect his and the prosecutor’s family members from attack.

Trump recently posted a photo of the judge’s daughter on Truth Social claiming that she “has just posted a picture of me behind bars, her obvious goal, and makes it completely impossible for me to get a fair trial.” According to the court, the Twitter account in question is not hers. A court spokesperson said of the account: “It is not linked to her email address, nor has she posted under that screenname since she deleted the account. Rather, it represents the reconstitution, last April, and manipulation of an account she long ago abandoned.” Whether Trump knew his post was untrue or just didn’t care is uncertain. Even assuming Justice Merchan’s daughter is likely no fan of Trump -- she works for a Democratic consulting firm – there are limits to how far one can go in attacking family members of those involved in a criminal trial. Defendants are limited in what they can say all the time out of concern for the integrity of the trial process and the safety of its participants. Trump should not receive special treatment – neither more nor less restrictive – than any other defendant. Following the seemingly false and inflammatory statements targeting his daughter, Justice Merchan issued an expanded gag order against Trump, noting (vehemently) that: “It is no longer just a mere possibility or a reasonable likelihood that there exists a threat to the integrity of the judicial proceedings. The threat is very real. Admonitions are not enough, nor is reliance on self-restraint. The average observer, must now, after hearing defendant's recent attacks, draw the conclusion that if they become involved in these proceedings, even tangentially, they should worry not only for themselves, but for their loved ones as well. Such concerns will undoubtedly interfere with the fair administration of justice and constitutes a direct attack on the Rule of Law itself.” While such concerns must indeed factor into the analysis of any gag order, a delicate balancing act is needed for court-ordered restrictions on speech. Courts uphold free speech and the First Amendment, yet they are themselves not venues for free speech, but rather islands of due process, less free-wheeling and more deliberative than the public square. When the raucous freedom of the public square intrudes upon the judicial process, limited and narrowly tailored protections to safeguard the judicial process can be necessary. This is an odd point of tension between competing constitutional and legal principles in the American system, but it is one necessary for the proper functioning of our judicial system. As with so many issues these days, this case is fraught with dilemmas. On the one hand, it is extremely problematic for a presidential candidate to face a judicial gag order. On the other hand, harshly (and perhaps falsely) attacking a judge’s family member is one of those situations – like falsely yelling “fire” in a crowded theater – where “imminent lawless action,” and an imminent threat to the integrity of the judicial proceeding in question, could arguably materialize. Whatever you think of this case against Donald Trump – some would characterize it as “lawfare” against him, some might flip the characterization around in the other direction – Donald Trump crossed a line. A limited – very limited – gag order is an acceptable response in a society that values the impartial administration of justice as well as speech. Judge Merchan should nonetheless remain vigilant to keep his own emotions in check, not be provoked into over-reacting, and give as much leeway as possible to the sometimes-hyperbolic speech inherent in the political process while still ensuring the integrity of the judicial process. Lindke v. Freed The U.S. Supreme Court is set to address several critical free-speech cases this session related to speech rights in the context of social media. One of those questions was recently settled, with the Court ruling on whether an official who blocks a member of the public from their social media account is engaging in a state action or acting as a private citizen. Answer: It depends on the context.

Writing for a unanimous Court in the case of Lindke v. Freed, Justice Amy Coney Barrett reaffirmed that members of the public can sue a public official where their actions are “attributable to the State” (consistent with U.S.C. §1983). In order to make that determination, the Court issued a new test, holding that: “A public official who prevents someone from commenting on the official’s social-media page engages in state action under §1983 only if the official both (1) possessed actual authority to speak on the State’s behalf on a particular matter, and (2) purported to exercise that authority when speaking in the relevant social-media posts.” This is a holistic analysis, consistent with the Protect The 1st amicus brief filed in O’Connor-Ratcliff v. Garnier. We argued that “no single factor is required to establish state action; rather, all relevant factors must be considered together to determine whether an account was operated under color of law.” That case, along with the Court’s banner case, Lindke v. Freed, is now vacated and remanded for new proceedings consistent with the Court’s novel test. When, as the Court acknowledges, “a government official posts about job-related topics on social media, it can be difficult to tell whether the speech is official or private.” So the Court set down rules. A state actor must have the actual authority – traced back to “statute, ordinance, regulation, custom, or usage” – to speak on behalf of the state. However, should an account be clearly designated as “personal,” an official “would be entitled to a heavy (though not irrebuttable) presumption that all of the posts on [their] page were personal.” In Lindke v. Freed, the public official’s Facebook account was neither designated as “personal” nor “official.” Therefore, a fact-specific analysis must be undertaken “in which posts’ content and function are the most important considerations.” As the Court explains: “A post that expressly invokes state authority to make an announcement not available elsewhere is official, while a post that merely repeats or shares otherwise available information is more likely personal. Lest any official lose the right to speak about public affairs in his personal capacity, the plaintiff must show that the official purports to exercise state authority in specific posts.” When a public official blocks a citizen from commenting on any of his posts on a “mixed-use” social media account, he risks liability for those that are professional in nature. Justice Barrett writes that a “public official who fails to keep personal posts in a clearly designated personal account therefore exposes himself to greater potential liability.” It's always been good policy to keep official and private accounts separate. The public must be able to have access to government-issued information, whether through a social media account or a public notice posted on the door of a government building. Moreover, citizens should be able to speak on issues of public concern, whether through Facebook or in a public square. Officials – presidents and former presidents included – should take note. |

Archives

June 2024

Categories

All

|

ABOUT |

ISSUES |

TAKE ACTION |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed